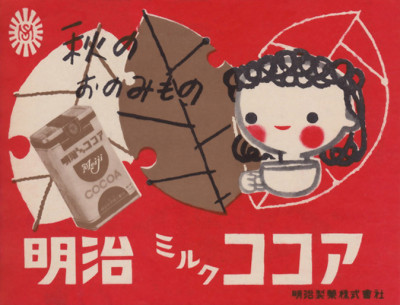

(Photo from this cool retro blog, which I found via this excellent blog post waxing nostalgic about Japanese whiskey.)

お待たせしました! and 明けましておめでとうございます!

Apologies for the long delay between posts. Thanksgiving to New Years is a long blur, but I have, in exchange for that delay, a hefty post looking at more hidden Murakami passages in both translation and revision from Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. Without further ado…

Chapter 13 is in the Hard-boiled Wonderland section of the novel. Watashi wakes up from shuffling, goes to meet the chubby granddaughter after she calls in a panic, kills time at a supermarket waiting for her, and then—when the girl doesn’t show up—returns home to sleep and to confront the oddly sized thugs looking to break into the information black market. They trash his place, end of chapter.

There are small cuts in this chapter (sadly one of the やれやれs gets axed) and there are enormous cuts. The two most sizable cuts happen for basically the same reason: superfluous characterization. Strangely enough, they are both cut from both the 1990 Murakami revision and the 1991 Birnbaum translation. Hmm…

I’ll give them to you in reverse order, otherwise known as the order of increasing interest and the order of increasing length.

In the 1985 version, we get more details about the background of the dwarfish thug. He advises Watashi to give up his beer habit but then admits to two vices of his own: smoking and sweets:

私は肯いて同意した。

男は煙草をまた一本とりだして、ライターで火をつけた。

「俺はチョコレート工場の横で育ったんだよ。それでたぶん甘いもの好きになっちまったんだろうね。チョコレート工場といってもさ、森永とか明治とか、ああいう大きいのじゃなくてさ、小さな名もない町工場でさ、ほら駄菓子屋とかスーパーマーケットのバーゲンとかで売っているような、ああいうゴツゴツした素気ないやつを造るところなんだ。それでなにしろ、毎日毎日チョコレートの匂いがするんだな。いろんなものにチョコレートの匂いが染みついちまうんだ。カーテンとか枕とか猫とか、そういうあらゆるものにさ。だからチョコレートは今でも好きだよ。チョコレートの匂いをかぐと子供の頃のこと思いだすんだ」

男はローレックスの文字盤にちらりと目をやった。(231-232)

I nodded in agreement.

The man took out another cigarette and lit it with his lighter.

“I grew up next to a chocolate factory. That’s probably why I ended up with a sweet tooth. I say chocolate factory, but I’m not talking Morinaga or Meiji or anything big like that. Just a tiny, no-name neighborhood chocolate factory. A place that makes the gross crap that ends up in the bargain bin at the supermarket. In any case, it smelled like chocolate every day. That chocolate smell got into all sorts of crap. The curtains, pillows, the cat, shit like that. Which is why I still like chocolate to this day. When I smell chocolate, I think of my childhood.”

The man glanced at his Rolex.

This is, perhaps, a typically Murakami-esque detail in that it links the mind and body and seeks to explain the compulsions of human behavior. But it’s also totally unnecessary: these guys are supposed to be caricature, not fleshed out characters. Although perhaps growing up alongside a crappy little chocolate factory is a perfect caricature-like detail.

(On a side note, here’s a clue as to why the guy might be associating cigarettes and chocolate, other than them both being bad habits:

)

At any rate, Murakami thought better of it the second time around and cut it out of the 1990 version:

私は肯いて同意した。

男はローレックスの文字盤にちらりと目をやった。 (184)

I nodded in agreement.

The man glanced at his rolex.

But he also cuts the cigarette line, which results in a phantom cigarette a few pages later. It’s like those scenes in movies where the costume people forget what someone was wearing and it suddenly changes in the next scene: the thug is suddenly ashing a cigarette he never lit on the floor.

Birnbaum takes care of this easily in his translation:

He lit another cigarette, and glanced at the dial of his Rolex. (135)

The second passage is much more substantial and very “improvised.” Whenever I see passages like this, it always reminds me of the comparisons that Murakami always gets to a jazz soloist. And then I remember that I hate John Coltrane (most Coltrane). I think this technique works in more controlled bursts (“The 1963/1982 Girl from Ipanema”), but it can be distracting in novels.

This passage is fun enough, I guess. Take a look:

それで私は反対側の壁にはってある煙草のポスターに目をやった。つるりとした顔の若い男が火のついたフィルターつきの煙草を指にはさんで、ぼんやりとした目つきで斜め前方を見ていた。煙草の広告モデルはどうしていつもこういう〈何も見てない・何も考えていない〉という目つきができるのだろう。

煙草のポスターではフランクフルトのポスターを見ているときほど長く暇がつぶせなかったので、私はうしろを向いて、がらんとしたマーケットの店内を見まわした。スタンドの正面には果物の缶詰が巨大な蟻塚みたいに高く積みあげてあった。桃の山とグレープフルーツの山とオレンジの山が三つ並んでいる。その前には試食用のテーブルが置かれていたが、まだ夜も明けたばかりなので、試食サービスは行われてはいなかった。朝の五時四十五分から果物の缶詰を試食する人はいない。テーブルのわきには〈USA・フルーツ・フェア〉というポスターがはってあった。プールの前に白いガーデン・チェアのセットがあり、そこで女の子がフルーツの盛りあわせを食べていた。金髪でブルー・アイズで脚が長くよく日焼けした美しい娘だった。フルーツの広告写真にはいつも金髪の娘がでてくる。どれだけ長く見つめていても、目を離した次の瞬間にはどんな顔だったかまるで思い出せない——というタイプの美人だ。そういうタイプの美しさが世の中には存在する。グレープフルーツと同じで、見わけがつかない。

酒類の売り場はレンジスターが独立していたが、そこには店員はいなかった。まともな人間は朝食前に酒を買いに来たりはしないからだ。だからそこの一郭には客の姿もなく店員の姿もなく、酒瓶だけが植木されたばかりの小型の針葉樹といった格好で静かに並んでいた。ありがたいことに、このコーナーにはポスターが壁一面にはってあった。数えてみるとブランディーとバーボン・ウィスキーとウォッカが一枚ずつ、スコッチ・ウィスキーと国産のウィスキーが三枚ずつ、日本酒が二枚とビールが四枚あった。どうして酒のポスターだけがこんなに数多くあるのか、私にはよくわからない。あるいはそれは酒というものがあらゆる飲食品の中でもっとも祝祭的な性格を有しているからかもしれない。

しかし暇をつぶすにはもってこいだったので、私は端から順番にそのポスターを眺めていった。それで、その十五枚のポスターを眺めて、私にわかったことは、あらゆる酒の中ではウィスキーのオン・ザ・ロックが視覚的にいちばん美しいということだった。簡単に言えば、写真うつりが良いのだ。底の広い大柄なグラスにかき氷を三つか四つ放り込み、そこに琥珀色のとろりとしたウィスキーを注ぐ。すると氷のとけた白い水がウィスキーの紅白色に混じる前に一瞬すらりと泳ぐのだ。これはなかなか美しいものだった。気をつけてみると、ウィスキーのポスター写真の殆どにはオン・ザ・ロックがうつっていた。水割りでは印象が薄いし、ストレートでは間がもたないのだろう。

もうひとつ気づいたのは、つまみのうつっているポスターがないということだった。ポスターの中でも酒を飲んでいる人間は、誰もつまみを食べていないのだ。みんなただ、酒を飲んでいるのだ。これはたぶん、つまみがうつったりすると酒の純粋性が失われると考えられているかもしれない。あるいはつまみが酒のイメージを固定してしまうからかもしれない。あるいはそのポスターを見る人間の注意がつまみの方にそれてしまうからかもしれない。それはなんとなく分かるような気がした。ものごとにはすべからく理由というものがあるのだ。

ポスターを眺めているうちに六時になった。が、太った娘はまだ現れなかった。 (219-221)

I looked at the cigarette poster on the opposite wall. A shiny-faced young man holding a filter-tip cigarette looked absentmindedly askance into the distance. I wondered how the models for cigarette ads are always able attain that thought-free I’m-not-looking-at-anything look in their eyes.

I couldn’t kill as much time staring at the cigarette poster as I had with the Frankfurt poster, so I turned around and looked over the empty supermarket. At the front of the displays, cans of fruit were stacked into huge piles like enormous anthills. There was a mountain of peaches, a mountain of grapefruits, and a mountain of oranges, three altogether. In front of all that, there was a table for samples, but the day had only just dawned, so they weren’t doing the sample service. No one comes to try fruit at five forty-five in the morning. On the side of the table, there was a “USA Fruit Fair” poster. There was a white garden chair set in front of a pool, and a girl was there eating from a fruit platter. She was a beautiful girl with blond hair, blue eyes, long legs, and a dark suntan. Photos for fruit ads always use blondes. No matter how long you stare at the girls, though, the second you look away, you can’t even remember what they looked like – that’s the kind of beauties they use. That kind of beauty exists all over the world. Just like grapefruits, you can’t tell them apart.

Alcohol sales had a separate register, but there was no clerk there. Because decent folks don’t do things like go shopping for booze before breakfast. So there were no customers or employees in that whole section, which made the bottles of booze seem lined up quietly like bonsai pines that had just been planted. Thankfully, the wall in this section was covered in posters. I counted them up: there was one each of brandy, bourbon, and vodka, three of both scotch and Japanese whiskey, two for sake, and four for beer. I didn’t know why alcohol was the only thing that had so many posters. Maybe it was because it provides the most festive personality of all the different types of food and drink.

However, they were perfect for killing time, so I started at the side and looked at the posters one by one in order. As I looked at those fifteen posters, I realized that of all the boozes, whiskey on the rocks is the most visually appealing. To put it simply, it’s photogenic. Throw three or four big chunks of ice into a wide-bottomed glass, pour in some viscous, amber whiskey, and there’s this moment just before the ice melts and light-colored water mixes with the amber when the ice swims lithely in the liquor. It’s a sight to see. If you pay attention, you’ll realize that most whiskey posters are photos of whiskey on the rocks. I guess whiskey and water looks too weak, and straight must feel like something is missing.

I also realized that there weren’t any posters with beer snacks. None of the drinkers in any of the posters were eating anything. Everyone was just drinking. Maybe this is because they thought the booze would lose its purity if it shared the spotlight with snacks. Or that the snacks would stereotype the booze. Or that the viewers of the posters would focus on the snacks instead of the beer. Those are things I could understand. There’s always a reason behind things.

As I was looking at the posters, it turned six o’clock. But the fat girl still hadn’t appeared.

I’m not totally confident with the entire translation (especially with the last line in the penultimate paragraph – there must be something better than that), but hopefully it’s good enough to give you a sense of the original and what Murakami is doing…which is going on and on about how he feels the world works. In this case, he’s breaking down poster theory. Not exactly critical to the book. And, again, Murakami notices this in time for the revision:

それで私は反対側の壁にはってある煙草のポスターに目をやった。つるりとした顔の若い男が火のついたフィルターつきの煙草を指にはさんで、ぼんやりとした目つきで斜め前方を見ていた。煙草の広告モデルはどうしていつもこういう〈何も見てない・何も考えていない〉という目つきができるのだろう。

そんな風に店に貼ってあるいろんなポスターをぼんやりと眺めているうちに六時になった。が、太った娘はまだ現れなかった。 (175-176)

I looked at the cigarette poster on the opposite wall. A shiny-faced young man holding a filter-tip cigarette looked absentmindedly askance into the distance. I wondered how the models for cigarette ads are always able attain that thought-free I’m-not-looking-at-anything look in their eyes.

And as I was gazing at all the different posters on the wall of the store, it turned six o’clock. But the fat girl still hadn’t appeared.

Birnbaum, too, takes an axe to this ginormous aside; he cuts even more than Murakami:

I turned my gaze to the poster on the opposite wall. A shiny-faced young man holding a filter-tip was staring obliquely into the distance. Uncanny how models in cigarette ads always have that not-watching anything, not-thinking-anything look in their eyes.

At six o’clock, the chubby girl still hadn’t shown. (130)

But he’s nicer than I am to the girl – “chubby” is a more sympathetic choice than “fat.” Probably the right choice.

It may still be too soon to say (I know that there are more whiskey-related scenes later in this book), but I’m not sure these asides will pay off. It will be interesting to see. The watermelon cut from earlier, for example, I think works because of the way Murakami wove the idea of watermelons into the first chapter as a metaphor for the brain. Here we will have to wait and see.