Here we are, the final chapter of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. I first read this book during the summer of 1999. I remember the first 100 pages being a slog and then just flying through the second half.

(I was visiting colleges while I read the book, and it had me convinced that I wanted to study cognitive neuroscience, even though the only thing I knew about cognitive neuroscience was the limited perspective of Murakami’s old man scientist. By “I want to study cognitive neuroscience” I basically meant “I really like this book I’m reading right now by Haruki Murakami.”)

I finished the book ravenously as I was on a flight home to New Orleans, worried that we might crash or I might otherwise expire—like our embattled data agent—and not know how the book ended.

Fortunately I’ve survived 20 years and finished the book in both languages. Pretty cool.

Here are the previous Murakami Fest posts:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year Eleven: Embers, Escape, Window Seats

Chapter 40 “Birds” is the last chapter of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. Boku and his shadow have arrived at the Southern Pool and stand at its edge quietly for a moment just looking at it as the snow falls around them. When the shadow suggests they jump in, Boku says he’s staying and can’t go. He’s realized he has a responsibility to everything in the Town because he’s created them all; they’re all part of him. The shadow is angry and they discuss what it means to stay—the conversation is treated quite differently in translation than the original. Then the shadow jumps in the pool. Boku turns back toward the town with thoughts of the Librarian and his accordion, and the book ends.

Here’s the conversation the two have in the original Japanese:

影は立ちあがって、たまりの静かな水面をじっと見つめた。降りしきる雪の中に身じろぎひとつせずに立った影は、少しずつその奥行を失い、本来の扁平な姿に戻りつつあるような印象を僕に与えた。長いあいだ二人は黙りこんでいた。口から吹きだされる白い息だけが宙に浮かび、そして消えていった。

「止めても無駄なことはよくわかった」と影は言った。「しかし森の中の生活は君が考えているよりずっと大変なものだよ。森は街とは何から何までが違うんだ。生き延びるための労働は厳しいし、冬は長く辛い。一度森に入れば二度とそこを出ることはできない。永遠に君はその森の中にいなくてはならないんだよ」

「そのこともよく考えたんだ」

「しかし心は変わらないんだね?」

「変わらない」と僕は言った。「君のことは忘れないよ。森の中で古い世界のことも少しずつ思いだしていく。思いださなくちゃならないことはたぶんいっぱいあるだろう。いろんな人や、いろんな場所や、いろんな光や、いろんな唄をね」

影は体の前で両手を組んで、それを何度ももみほぐした。影の体に積もった雪が彼に不思議な陰影を与えていた。その陰影は彼の体の上でゆっくりと伸びちぢみしているように見えた。彼は両手をこすりあわせながらまるでその音に耳を澄ませるかのように、軽く頭を傾けていた。

「そろそろ俺は行くよ」と影は言った。「しかしこの先二度と会えないというのはなんだか妙なものだな。最後に何て言えばいいのかがわからない。きりの良いことばがどうしても思いつけないんだ」

僕はもう一度帽子を脱いで雪を払い、かぶりなおした。

「幸せになることを祈ってるよ」と影は言った。「君のことは好きだったよ。俺が君の影だということを抜きにしてもね」

「ありがとう」と僕は言った。 (590-591)

My shadow stands up and stares at the calm surface of the Pool. Standing absolutely still in the heavy snow, he gives the impression that he’s gradually losing all of his depth and returning to his original flatness. We are silent for a long while. Only puffs of white breath emerge from our mouths into the air and then disappear.

“I knew it was futile to try and stop you,” my shadow says. “But life in the Woods will be much more difficult than you think. The Woods are entirely different from the Town. It’s tough work to survive, and winter is long and trying. Once you enter, you cannot leave. You’ll have to remain in the Woods forever.”

“I’ve considered this, too.”

“And you haven’t changed your mind?”

“No,” I say. “I won’t forget you. I’ll slowly start to remember things about the old world as well. There are likely many things that I’ll have to remember. Many people, places, lights, songs.”

My shadow crosses his arms in front of him and rubs them together several times. The snow that collects on his body gives him a mysterious shadow that seems to expand and contract over him. He rubs both hands together and tilts his head ever so slightly as though listening for the sound they make.

“I’m going to go,” he says. “But it’s strange to think we’ll never see each other again. I don’t know what to say in the end. I can’t think of the right words to leave things.”

I take off my hat again, brush off the snow, and put it back on.

“I hope that you’ll be happy,” my shadow says. “I loved you. And not just because I was your shadow.”

“Thank you,” I say.

And here is Birnbaum’s official translation, which makes some significant adjustments:

My shadow rises and stares at the calm surface of the Pool. He stands motionless amid the falling snow. Neither of us says a word. White puffs of breath issue from our mouths.

“I cannot stop you,” admits my shadow. “Maybe you can’t die here, but you will not be living. You will merely exist. There is no ‘why’ in a world that would be perfect in itself. Nor is surviving in the Woods anything like you imagine. You’ll be trapped for all eternity.”

“I am not so sure,” I say. “Nor can you be. A little by little, I will recall things. People and places from our former world, different qualities of light, different songs. And as I remember, I may find the key to my own creation, and to its undoing.”

“No, I doubt it. Not as long as you are sealed inside yourself. Search as you might, you will never know the clarity of distance without me. Still, you can’t say I didn’t try,” my shadow says, then pauses. “I loved you.”

“I will not forget you,” I reply. (399)

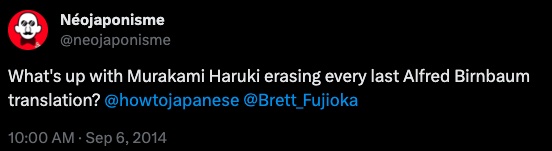

He’s clearly taken some liberties in dictating through the shadow what it will mean for Boku to stay in the Town. I had to look at the 1985 paperback version twice just to make sure that Murakami himself hadn’t made cuts to the 1990 Complete Works edition; when Birnbaum and the Complete Works editions don’t align, often it’s been because Birnbaum was clearly translating based on the 1985 edition. But that’s not the case here. The “You will merely exist” feels so appropriate for this world, but it’s not in the Japanese.

That said, Birnbaum’s translation is just supreme—“different qualities of light” is such a perfect line.

***

So what have we learned?

We’ve learned that Murakami made changes to the original version of Hard-boiled Wonderland that was published in 1985 for the Complete Works version that was published in 1990. He cuts some name drops, some random asides, and some jokes. Some changes are a little strange, and sometimes as small as a single sentence in a chapter. I don’t think it’s too farfetched to say that many of these changes were made after Murakami saw the English translation. Too many of the cuts coincide too perfectly with cuts that Birnbaum made in translation.

It’s conceivable that Birnbaum was working based off of the manuscript for the 1990 version, but there are places that Murakami cuts and Birnbaum keeps, which would be strange unless he was actively comparing the two different manuscripts. I think it’s more likely he completed the translation in 1988 or 1989, Murakami saw the translation during the editing process, and then he had time to make adjustments to the Complete Works text. I wonder whether he would have read the English himself or whether the editors noted specifically which sections were being removed from the Japanese.

At any rate, this was a very productive time during Murakami’s career, and we’ve learned that he was recycling themes and images across works, notably from his 1985 short story collection Dead-heat on a Merry Go Round.

We’ve learned that Birnbaum is a brilliant writer and translator. His prose is beautiful and hilarious. He has excellent control over the tone of the work and how that builds the worlds, especially in the End of the World sections.

But we also know that he has several techniques that “improve” the work in translation. He uses space breaks to create dramatic moments and trims the endings of chapters so that they’re either dramatic dialogue or in media res. He adds entirely new lines to make things more dramatic.

He does, however, alter the work at times. He trims sections where Murakami tends to run long in his usual improvisational way, mostly with good results but occasionally something nice gets axed. He tends to cut places where Watashi brings in the outside world, sections that point to a larger context for his feeling of helplessness, and suggest that it refers more broadly to the human condition.

Overall he dials down the sexiness. From the beginning he’s a little less blatant about Watashi’s vision of the Girl in Pink. He dials back on a lovely exchange with the Librarian and cuts some of the sexy encounters between Watashi and the Girl in Pink entirely, including one where he drops his pants to show her his erection (!).

We’ve also learned that even the best translators make mistakes, or are forced into mistakes through their editors.

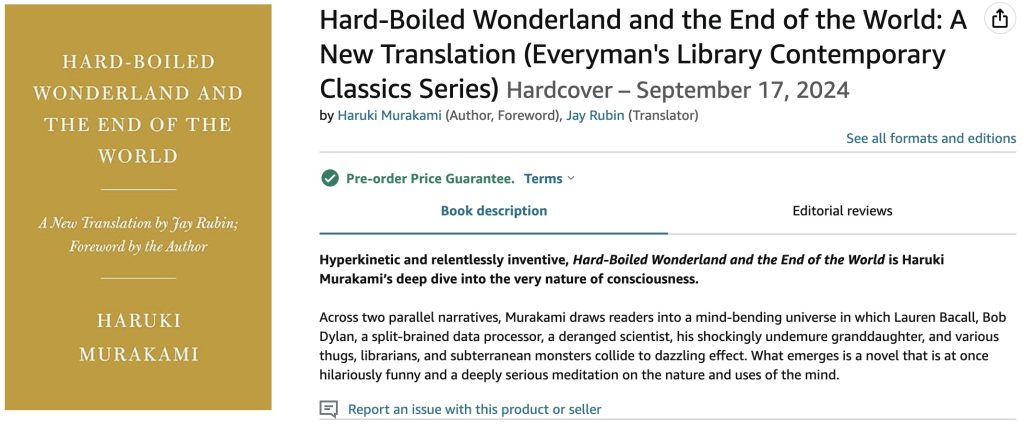

Hard-boiled Wonderland is really a perfect text to analyze Murakami’s editing process, how Japanese writers were translated during the 80s and early 90s (especially before they had much clout in the publishing industry and before the anime/manga boom really took hold), and the goals of translation more broadly. There are a probably a few other works that present opportunities this rich, notably Dance Dance Dance and Wind-up Bird Chronicle (both of which had extensive cuts in translation, about which Jay Rubin has been very transparent) and Hear the Wind Sing, Pinball 1973, and Norwegian Wood (all of which have been translated twice by multiple different translators). At the very least, I think someone could do a really good paper about Murakami’s preparation of the Complete Works texts.

I wonder whether Hard-boiled Wonderland was the only work he edited for re-publication. I have a feeling that this is not the case.

***

I was disappointed with the ending the first time I read the book. I wanted Boku to escape and Watashi to live. I wanted him to somehow succeed against everything he was facing—the System, the Factory, the Gatekeeper. I’d even started to wonder whether the Girl in Pink pulled a Psycho move and had him frozen in her apartment. But the ending has grown on me.

We have an approximation of Murakami’s vision of escape from the novella “The Town and its Uncertain Wall,” which was a first draft of sorts for this novel. The narrator escapes and ends up being tortured by nostalgic yearnings of life in the Town. We know nothing about this narrator—it’s not the clearly defined Murakami male persona from Hard-boiled Wonderland—but it’s easy to imagine Watashi in the Hell of a forced continued existence in the modern world, with an itch he’s never able to scratch (presumably after he’s separated himself from that interior world); the whole novel has basically been to show how miserable he has it. Better for him to pass into the tautology of his inner experience.

I do wonder sometimes whether Murakami will write a sequel. He’s left enough threads unfollowed—we have the Girl in Pink freezing the body and the Woods are yet unexplored and filled with different people. But more and more frequently Murakami just repeats “I never remember what I wrote” when asked about past works. More recently, he only seems to write sequels immediately after completion of a book as with 1Q84 and Wind-up Bird Chronicle.

And part of me doesn’t want him to change anything. It’s such an interesting work as is.

I also wonder whether there will be another attempt at translation. I imagine this won’t happen until after Murakami dies, perhaps not even until the work goes into the public domain. We’ll all have expired into our personal Ends of the World by that point. And to be honest, I don’t know that the original Birnbaum translation can be topped—I think this is something else we’ve learned through this project.

____

Update:

I’m realizing now that readers who come across this post may not understand the difference between Murakami Fest and this Hard-boiled Wonderland Project. Although they overlapped at times, I started blogging about untranslated Murakami works once a year around the Nobel Prize announcements in the early years of the blog. In 2012, in an attempt to post on the site more frequently, I started blogging about the translation of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. You can see an index of all those posts on this page.

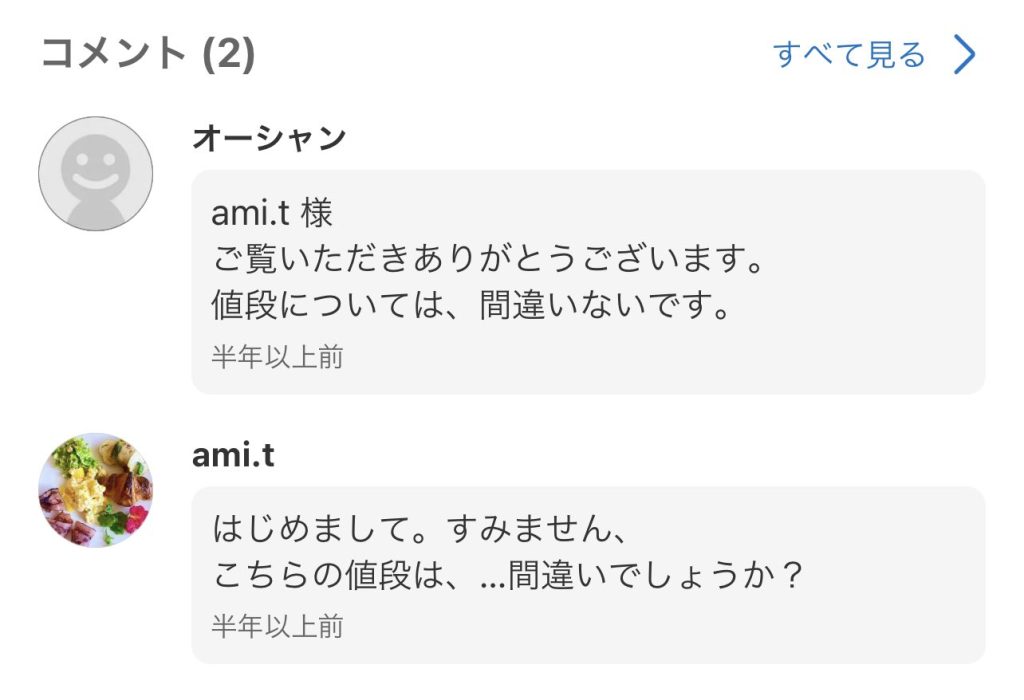

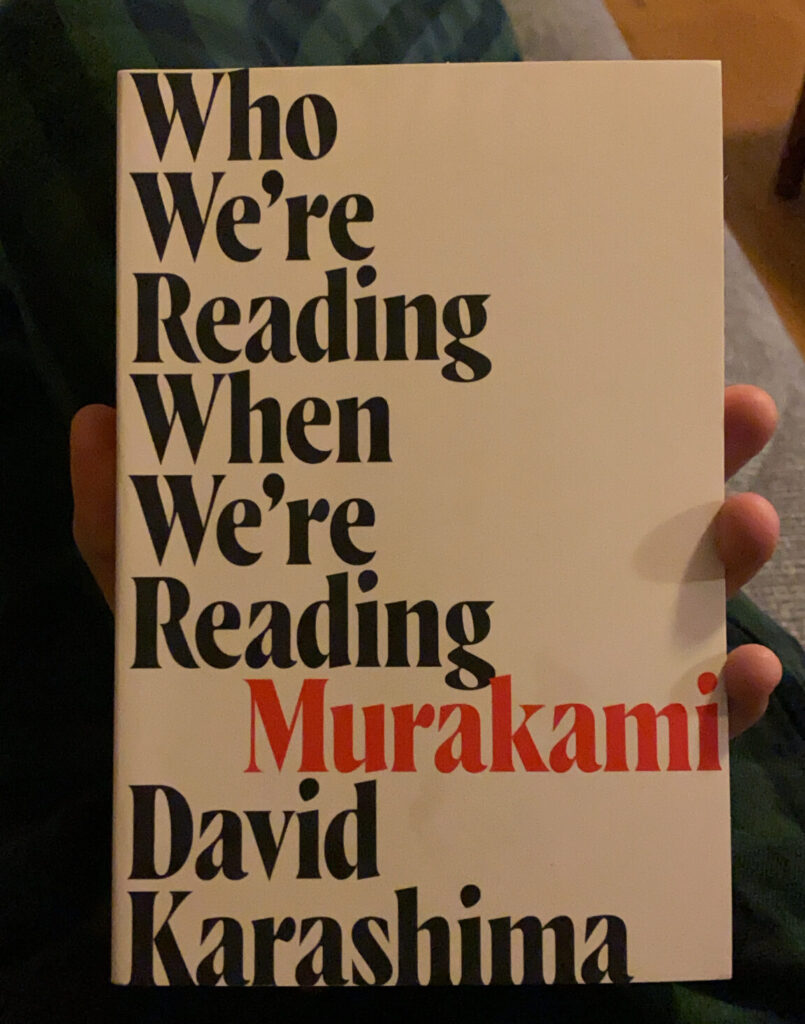

This is pretty wild to me because they’re so totally different. The former is so abstract while Sheep is more surreal. I actually own a copy of both. A friend got me A Wild Sheep Chase years ago, and the Dead Heat first edition was one of the first purchases I made when I moved to Japan…I imagine it was significantly less expensive. You can see more of Okamoto’s work

This is pretty wild to me because they’re so totally different. The former is so abstract while Sheep is more surreal. I actually own a copy of both. A friend got me A Wild Sheep Chase years ago, and the Dead Heat first edition was one of the first purchases I made when I moved to Japan…I imagine it was significantly less expensive. You can see more of Okamoto’s work