Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year Eleven: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year Twelve: Distant Drums, Exhaustion

Nonfiction gives Murakami the opportunity to flex his writing muscles in really interesting ways, one of which is character work. He’s experiencing life in Europe with his wife, and he spends a lot of time with his thoughts (as I think you’ve seen with the first two posts), but once he gets on the road, he actively includes the people he encounters, the first of which is a woman named Valentina who is the realtor or property manager who introduces them to the house where they stay on the island of Spetses. This is their first destination immediately after Spetses.

Murakami does a great job of capturing Valentina and her tendency to draw out the vooooowels of words. She says she’s a writer, too, who writes poems but needs another job to live, and she seems disappointed with Murakami. She expected more, which doesn’t seem to surprise Murakami:

Sometimes I get to thinking that I lack what might best be termed an “aura” as a writer (or an artist). Even in Japan, I often get mistaken for a bakery deliveryman or a supermarket worker. I’ll be shopping and a stranger will ask, “Hey, where’s the red pepper?” (And of course I go ahead and tell them where it is.) But this isn’t entirely because of what I wear. Occasionally I’ll be dressed up nice in a dark suit with a tie on, standing in a hotel lobby, and some old man will say, “Hey you, where’s the Tsuru-no-ma room?” So I couldn’t really fault Valentina. Auras—not that I know what purpose they serve, realistically—are something that’s clearly defined when you have them and totally absent when you don’t. Just like onsen and oil fields.

ときどき僕は思うのだけれど、どうも僕には作家としての(あるいは芸術家としての)オーラとでも称するべきものがいささか不足しているようである。日本にいてもよくパン屋の配達人とか、スーパーの店員に間違われたりする。買い物をしていると、知らない人に「ねえ、唐辛子どこにあるの?」ときかれたりする(そてまた、しっかり教えてあげちゃったりもする)。でもそれは服装のせいとばかりは言えないようである。たまにきちんとネクタイをしめて、ダークスーツを着てホテルのロビーに立っていても、どこかのおじさんに「おい君、鶴の間はどこかね?」と尋ねられたりもする。だから僕にはとてもヴァレンティナのことを責めたりはできない。オーラというものは―それが現実的にいったいどういう役に立つのか僕にはよくわからないけれど―あるところにはちゃんとあるし、ないところには全然ないのだ。温泉とか油田とかいったものと同じように。(44-45)

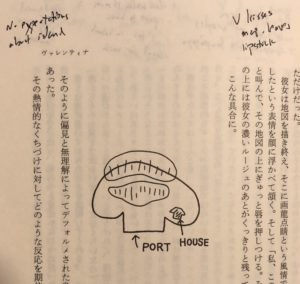

Murakami does go on to ridicule Valentina a little. She draws a very simple map of the island and marks the port and house. Murakami later learns that she’s drawn it upside down (basically) rather than aligned with the cardinal directions. And in a troublesome paragraph, he suggests that Valentina and all women in general value what they can see and experience over the overall impression of a map.

So not a great outing, but he does capture much of the impression that Valentina leaves, sometimes very literally:

When she finished drawing the map and marked the location of the house with a final flourish, she nodded with a very satisfied look on her face. She yelled, “I looooooooove this island!” and pressed her lips firmly against the map. Then she handed me the piece of paper. She had left the distinct mark of her thick lipstick on the map.

Like this:

The island, thus transformed by her distorted view and lack of understanding, was beautifully sealed by her lipstick.

At the time I didn’t know what kind of reaction she expected from such a passionate kiss (and I still don’t), so I just said, “Thank you” as I took the note, glanced at it, folded it in half, and put it in my pocket. Then I tried not to think about the map again.

彼女は地図を書き終え、そこに画竜点睛という風情で家の位置を書き入れると、いかにも満足したという表情を顔に浮かべて頷く。そして「私、この島だあああああああ好き(大好き)」と叫んで、その地図の上にぎゅっと唇を押しつける。そしてその紙を僕に手渡してくれる。地図の上には彼女の濃いルージュのあとがくっきりと残っている。

こんな具合に。

そのように偏見と無理解によってデフォルメされた島は、口紅によって見事に封印されたのであった。

その熱情的なくちづけに対してどのような反応を期待されているのか、僕にはその時まったくわからなかったので(今だってわからないけれど)、まあとにかく「どうも、ありがとう」と言って地図を受け取り、ちらっと見てから二つに折ってポケットにしまった。そしてそれ以上地図については考えいないようにした。 (51-52)

This feels like Murakami just getting started before he really gets into gear in some of the more rural places he visits. A lot to look forward to.

Small slip-up: you should have used “lipstick” instead of “rouge” in the sentence “She had left the distinct mark of her thick rouge on the map.”

While this usage may once have been appropriate, modern usage is to use “rouge” for blush (makeup) applied to the skin rather than lips. (Although Japan uses this borrowed word to denote lipstick).

Gah, I balked at lipstick when I was first working on this! Thanks for the note. I must not have Googled enough. I thought Murakami was going for a different word choice other than 口紅. It definitely reads more smoothly as “lipstick.”