Year 1: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year 2: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year 3: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year 4: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year 5: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year 6: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year 7: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year 8: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year 9: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year 10: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year 11: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year 12: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense, Rotemburo

Year 13: Murakami Preparedness, Pacing Norwegian Wood, Character Studies and Murakami’s Financial Situation, Mental Retreat, Writing is Hard

Year 14: Prostitutes and Novelists, Villa Tre Colli and Norwegian Wood, Surge of Death, On the Road to Meta, Unbelievable

Year 15: Baseball on TV

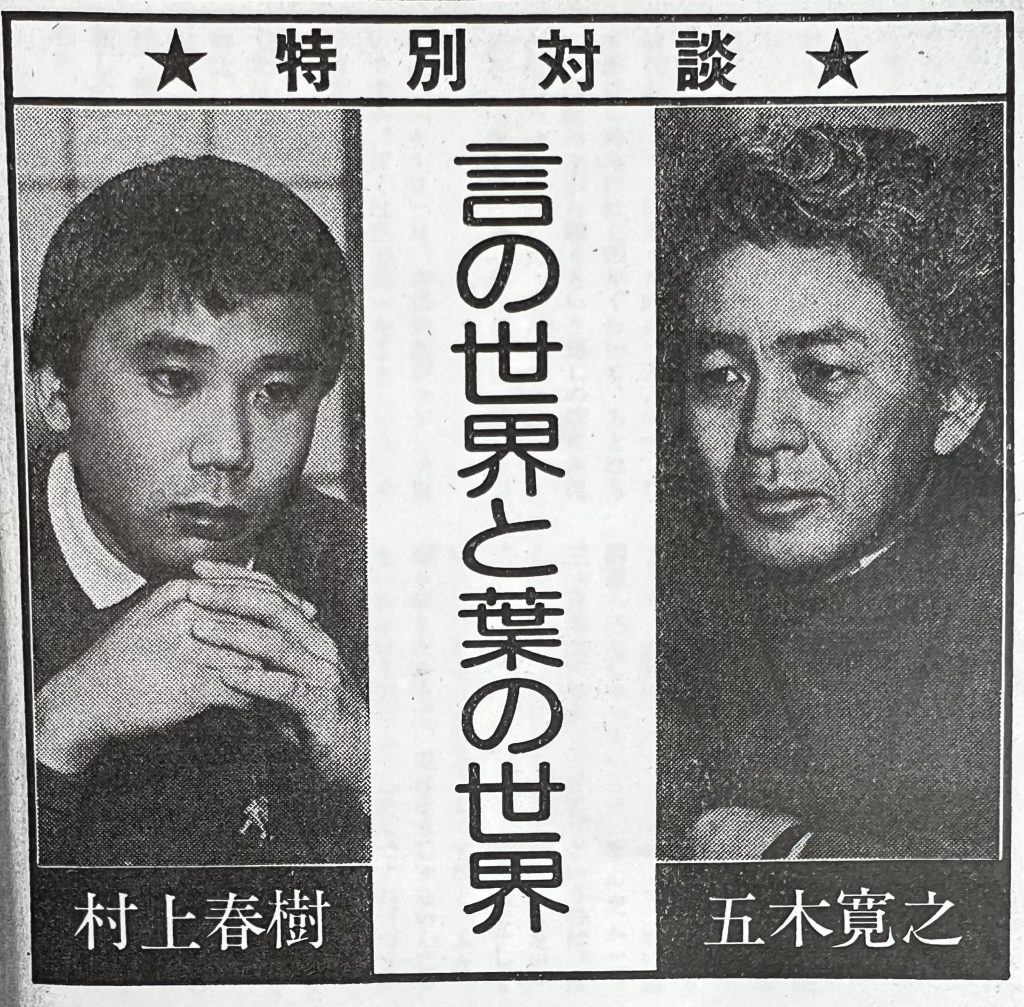

For Week 2 of Murakami Fest this year, I’m looking at the February 1983 issue of 小説現代 (Shōsetsu gendai), which includes a 対談 (taidan) conversation between Itsuki Hiroyuki and Murakami with the translation-defying title 言の世界と葉の世界 (Koto no sekai to ha no sekai, perhaps, “The world of deeds and the world of leaves”?).

Itsuki is an interesting writer. He’s a member of the rapidly dwindling 焼け跡世代 (Yakeato sedai, Generation of Ashes). He turned 90 this year and put out a new book of essays titled 捨てない生き方 (Sutenai ikikata, Living Without Getting Rid of Things), which seems like a sort of direct challenge to Kondo Marie.

He was born in Fukuoka but grew up in colonial Korea. He dropped out of Waseda and ended up working in radio and advertising in Kanazawa, but eventually lived in Russia and wrote about his travels a lot. He’s been prolific, mostly as a nonfiction writer, but he’s written some fiction as well.

In 1983, Itsuki was 50, an established presence, and Murakami would have been 34, having just published A Wild Sheep Chase, which won an award and took his writing to an entirely different level. Murakami uses keigo throughout the interview, and Itsuki is polite but doesn’t use keigo.

The conversation starts with Murakami’s background (he’s clearly the focus here), but quickly shifts to the jazz bar/cafe that Murakami is still running.

Itsuki I got a postcard once from a reader who was so happy. He’d been a huge fan of this cafe off the Chuo Line, I forget the name. He was a regular, and then it disappeared and he felt so lonely, like he’d lost a home. Then one day he stumbled into a cafe in Sendagaya and had this sense that the guy from the other store had to be the one running it. After looking into it, he realized that you were the one running it. I think that reader had good instincts, but things like that happen. Like running into a girl somewhere who suddenly disappeared on you in point in the past.

Murakami About the cafe—I’m actually really looking forward to closing it.

Itsuki Really now.

Murakami From the start, I always thought I’d close it after a few years. About two months ago I decided to close two months from now. And I’ve actually really been looking forward to it (laughs).

Itsuki It must be a cruel pleasure (laughs)

Murakami Well, I think it’s what my customers want as well. With music, and things surrounding music, everything keeps changing, and change is the truth; sometimes it’s a real kindness to let things go away rather than showing them in their changed state. I might be a little extreme with this line of thinking.

Itsuki That happens. It happened when we were in college. People are more passionate about the places that were around when we were in college and have disappeared than they are about the places that are still around now.

Murakami When I started my cafe, it was a major turning point for jazz cafes.

Itsuki A turning point how so?

Murakami The era of listening to jazz to appreciate it as music had just ended. I started right around ’74, and after that point mainstream culture had shifted to places where jazz was something to listen to while drinking.

五木 中央線沿線の何とかっていう喫茶店が好きで、そこに通っていたら、それがなくなちゃって、自分の居所がなくなったような淋しい思いをしていた。と、ある時たまたま千駄ヶ谷で喫茶店に入ったら、その店は絶対にあの店の人がやっているというふうに思えた、それでいろいろ調べたら、村上さんがやっていた店だったということがわかって、とってもうれしかったという葉書をもらったことがあってね。その読者の人の勘もいいけれども、そういうことがあるんだね。昔の、途中で消えっちまった女に、偶然にほかであったようなもんだったんでしょう。

村上 店というのはね、閉店しちゃうのが楽しみなんですよね。

五木 ほう。

村上 はじめから何年か経ったらもうやめちゃおうと思っているわけです。ふた月くらい前に、二ヶ月後にやめますっていうわけですよね。それがね、わりにたのしみなんですよね(笑)。

五木 残酷な楽しみだな(笑)。

村上 というか、お客の方もね、それを望んでるんじゃないかっていう気がするんですよね。結局、音楽にしても、その周辺のものにしても、どんどん変わっていきますし、変わるのが本当だと思うし、変わったものをみせられるよりは、なくしちゃったほうが本当の親切というもんじゃないか、という気がするんです。まあ、ぼくはわりに極端な考え方する方かもしれないですけど。

五木 それはあるだろうな。ぼくらの学生時代の頃にあって、いまなくなっちまった店を語るのほうが、今も残っている店のことを語るよりは熱があるものね。

村上 ぼくがはじめた頃はちょうどジャズ喫茶の大転換期だったんですよね。

五木 転換期っていうのは、どのへんですか。

村上 いわゆる鑑賞音楽としてジャズを聴く時代がちょうど終わった時だったんです。ぼくがはじめたのは七四年ぐらいで、あとはもう、酒飲みながら聴くと言う感じの店に主流が移っちゃった時代だったんですよね。(223)

Murakami introduces this word 親切 (shinsetsu, kind) that he ends up coming back to throughout the conversation. They talk about “city novels,” and Murakami’s development as a writer, where the word pops up again.

Murakami Even after my first and second novels, I didn’t feel like a novelist. I really wondered whether they were enough or not. Novels should be kinder toward the world. When Murakami Ryu wrote Coin Locker Babies, I found myself thinking the same thing again.

村上 一作目二作目を書いても、自分が小説家という感じはなかったですね。ただ、それだけでいいのか、よくないんじゃないかという気持ちはすごくあったんですよね。小説というものは世界に対してももう少し親切であるべきじゃないかってことですね。ちょうど村上龍が『コインロッカー・ベイビーズ』を書いて、やはり同じようなことを考えていたんじゃないかと思いました。 (225)

The conversation shifts to storytelling vs monogatari, “the world of deeds vs. the world of leaves” – artists living separately from the world to maintain their autonomy (?), the Japanese Constitution and how each generation experienced it differently, the death of the student movement, overcoming ego as a writer, and then how Itsuki began as a writer with an international view and became more focused on Japan. Murakami likens himself to this in an very interesting passage:

Murakami When I myself first started writing, I started by taking the techniques from people like Vonnegut, Brautigan, and Chandler and putting them into Japanese, but I really do feel like I’m heading toward something very Japanese.

Itsuki Looking at how you’ve progressed from Hear the Wind Sing to A Wild Sheep Chase, I think I’ve you’ve really changed a tremendous amount in a short period. Maybe it doesn’t appear that way on the surface, but I can tell that your awareness as a writer is changing.

Murakami I don’t know what that Japanese thing that I’m heading toward is. But I have this vague sensation that I’m working toward something inherent about Japan. Not a return to the Japanese roman or anything like that. I have, at the moment, this extreme desire to first assimilate it into my body. Only things that I’m able to touch are real, and everything else is just an illusion. So I’d like to be as kind as I can to the things I’m able to touch. And then I want writing to be the conclusion of that series of actions.

村上 ぼく自身も、最初に書いた時は、アメリカのボネガットだとかブローディガンとか、チャンドラーとか、そういうものの手法をただ日本語に移し替えるというところからはじまったんですけど、自分自身が非常に日本的なものに向かっているんじゃないか、という気持ちがものすごくあるんですよね。

五木 『風の歌を聴け』から今度の『羊をめぐる冒険』に至るまでの小説を見ていると、よく、これだけの短い期間でこんなに変わってきたな、と思うぐらい変わってきているよ。表には、そんなにはっきり見えないかもしれないけれども、作家の意識が変わってきているというのは、すごくよくわかります。

村上 その日本的なものが何か、というのはね、よくわからないんですけれどね。でも、なにか自分が日本の固有のものを目指しているんじゃないかということは、ぼんやり感じるわけです。ただ日本的浪漫への回帰とか、そういうんじゃなくて、自分の体にまず同化したいというところが、今、すごくあります。自分の体がじかに触れているものだけが本来のものであって、それ以外のものは結局のところ幻想なんじゃないかっていうことですね。だから、ぼくは自分が手を触れることができるものに対してはできる限り親切でありたいと思います。そして文章というのはそういった一連の行為の帰結でありたいと思うんです。 (233)

An interesting read. Not sure there’s anything truly groundbreaking, but it was a fun read, and we see Murakami shifting away from the kind of carefree, ironic attitude toward the world that characterized his early novels. At the end, Murakami notes that he “can’t” have kids but then immediately adds that he doesn’t have the confidence (確信がないんです) to have kids, which accounts for another piece of his biography.

It is interesting to see someone of Itsuki’s stature praising Murakami this heavily this early in his career. I think A Wild Sheep Chase deserved the praise, clearly, but Murakami wouldn’t be a truly mainstream writer for another four years when he put out Norwegian Wood. Itsuki must have seen something.