Year 1: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year 2: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year 3: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year 4: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year 5: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year 6: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year 7: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year 8: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year 9: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year 10: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year 11: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year 12: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense, Rotemburo

Year 13: Murakami Preparedness, Pacing Norwegian Wood, Character Studies and Murakami’s Financial Situation, Mental Retreat, Writing is Hard

Year 14: Prostitutes and Novelists, Villa Tre Colli and Norwegian Wood, Surge of Death, On the Road to Meta, Unbelievable

Year 15: Baseball on TV, Kindness, Murakami in the Asahi Shimbun – 日記から – 1982

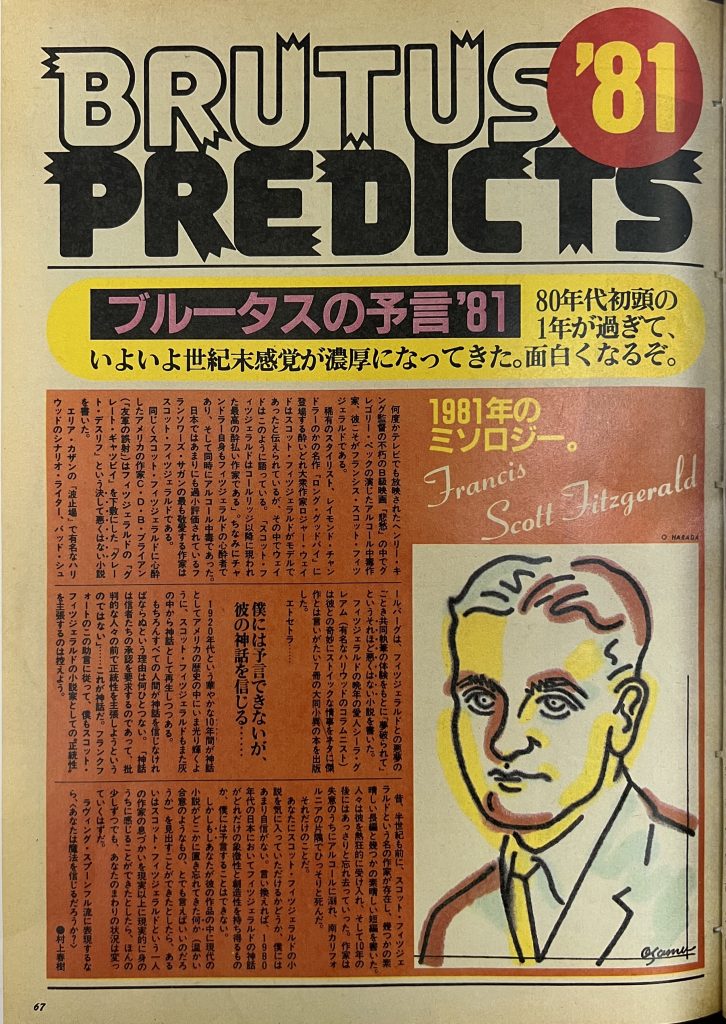

This week I’m looking at one of Murakami’s earliest appearances in the culture magazine Brutus. Murakami was featured in the February 1, 1981 issue, which had the title ブルータスの予言’81 (Brutus’ Predictions for ’81).

Murakami was one of several writers who contributed a page-long “prediction,” with his titled 1981年のミソロジー (The Mythology of 1981) which focuses on F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s kind of a strange way to play the assignment, but Murakami is a huge fan of Fitzgerald, so maybe it isn’t a surprise.

The piece starts by discussing all the odes to Fitzgerald in other works of art as well as writers who have admitted their admiration for him. Murakami then gives a short summary of Fitzgerald’s brief rise to the top and quick plummet, after which point he’s forgotten for several decades.

He ends the piece with these three paragraphs:

I’m not confident I can get you to appreciate Scott Fitzgerald’s fiction. To put it another way, I can’t predict whether the myth of Fitzgerald is symbolic or creatively compelling in Japan of the 1980s.

However, if you’re able to detect something (you might even call it a warm sense of understanding) in his works that’s been left out of contemporary fiction or if you’re able to sense something in Fitzgerald’s presence as a writer that’s so real it surpasses reality, to even the slightest degree, then the world around you will start to change.

To borrow a phrase from The Lovin’ Spoonful, “Do you believe in magic?”

あなたにスコット・フィッツジェラルドの小説を気に入っていただけるかどうか、僕にはあまり自信がない。言い換えれば、1980年代の日本においてフィッツジェラルドの神話がどれだけの象徴性と創造性を持ち得るものか、僕には予言することはできない。

しかしもしあなたが彼の作品の中に現代の小説がどこかに置き忘れてきた何か(温かい合意のようなもの、とでも言えばのだろうか)を見出すことができたとしたらあるいはスコット・フィッツジェラルドという一人の作家の息づかいを現実以上に現実的に身のうちに感じることができたとしたら、ほんの少しずつでも、あなたのまわりの状況は変わっていくはずだ。

ラヴィング・スプーンフル流に表現するなら、<あなたは魔法を信じるだろうか?>

It’s a bit of a filler piece, and the ending is basically just a hand wave, but overall it’s not poorly penned. Murakami is relatively early on the Fitzgerald bandwagon, although not the earliest. In the first half of the essays, one of the authors he mentions is C.D.B. Bryan:

Another great admirer of Scott Fitzgerald was the American author C.D.B. Bryan (Friendly Fire) who used Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby as the model for his novel The Great Dethriffe, which was not a bad book at all.

同じくスコット・フィッツジェラルドに心酔したアメリカの作家C・D・B・ブライアン(『友軍の誤射』)はフィッツジェラルドの『グレート・ギャツビイ』を下敷にした『グレート・デスリフ』という決して悪くない小説を書いた。

Bryan came up in Murakami Fest 2020 in part of Distant Drums. Murakami was just finishing up his translation of The Great Dethriffe while in Europe. So this is an unexpected way to close the loop on that. The Great Dethriffe was published in 1970. Murakami somehow read it between then and 1981, and then translated it five years later while he was writing Norwegian Wood.

That’s pretty impressive. There’s a good chance Murakami read it well before he became a writer, sat on his admiration of the novel for years, and then once he became a writer, was finally in the position to translate it, 10 years after it was initially published. As I mentioned in the blog post two years ago, the book is pretty widely recognized as being not very good, despite Murakami’s opinion, but it shows impressive dedication on Murakami’s part.