Japanese students living outside of Japan sometimes have trouble finding reading material. There are no BookOFFs or Kinokuniyas in, say, Omaha, Nebraska. And most of the ebook sales platforms are region locked.

You might counter with the fact that the Internet itself is a giant source of reading material, one that is ever-expanding thanks to its explosive nature. However, as with many explosive phenomena, it can be hard (and messy?) to sort through the results. What’s good reading material? What’s bad reading material?

This question gets less and less important the better you get at Japanese; it’s all practice, and you’ll quickly be able to sort out whether you’re enjoying it or not. Those at the lower- and middle-intermediate levels don’t have the chops it takes to sort through the expanse—they could, but it might exhaust the muscles that they should be saving for more “quality” exposure.

Amazon has a solution. A few months ago I learned that the Amazon Singles program has been offering Singles in Japanese in the U.S. and other Amazon stores. Singles are short stories, essays, novellas, etc. and they range in price from $0.99 to $7.00. Most are $0.99 to $3.99. You can download these and go at them on your phone or Kindle without ever leaving the country.

I picked up 天上の飲み物 (“Drink of the Heavens”) by Shion Miura to test drive the system, and I have to say it’s great:

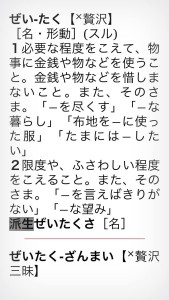

All these screenshots are from the iPhone interface. You can install dictionaries which pop up when you highlight text. The J-J dictionary is great for forcing reading practice:

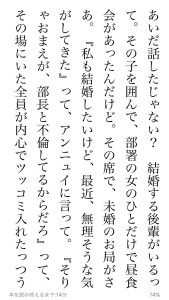

And there’s J-E if you’re struggling:

Highly recommended. Get ye to the Amazon Singles store.

This is a good reminder that ease of access doesn’t mean you’ll be accessing quality material. The story itself was only okay. Shion Miura is well known for the Naoki Prize-winning まほろ駅前多田便利軒.

天上の飲み物 is about a wine-obsessed vampire, and it’s highly concept driven. It reminded me a lot of the Yoko Ogawa story 涙売り that was part of the JLPP Translation Contest. They both start with narrators introducing a magic realist premise that the author uses to explore an idea: in Ogawa’s case, she looks at sacrifice for art, more specifically sacrifice in support of an artist, and Miura looks at relationships and love for someone who lives forever, which she uses to reflect on the state of relations in Japan.

Neither story has much of a plot. It’s mostly the narrator rambling on, but Ogawa’s story feels more specific, and there’s a small bit of plot toward the end: a band goes to play a show outside. Miura is far more general and the only plot is the narrator and his love interest lying around. Snore. Still, it’s good practice.

A couple of language highlights:

I learned that 収集 has the alternate reading 蒐集:

And I learned that ennui is written in katakana and can be used as an adverb (ennuifully?):

I’m going to have to look through the rest of the Singles on offer. I’d seen Miura’s name all over covers of literary magazines while I was living in Japan but I never had a chance to read her stories, so that was nice. I hope Amazon is able to add to this program. Very valuable for students living abroad.