I come from a family of thrifters and hoarders. It’s not fatal—we throw out our trash regularly and occasionally sort through the pantry—but we do accumulate stuff. And take pleasure in the hunt. After three big moves in the past 15 years, two of them across the Pacific, I’ve been better about resisting temptation. I managed not to purchase the pristine copy of Final Fantasy VI I came across in a Wakayama thrift store on sale for 1,000 yen on Christmas Day, 2022, but I still remember it vividly.

Recently the website Mercari has served as a sort of thrifting Methadone. I keep a few saved searches (保存した検索条件) but opt out of daily email notices. It’s a great way to fill empty time on the train, pretending to listen to podcasts when I’m really looking through used board games and books.

Browsing Mercari has also made me consider what retains value in Japan and what doesn’t. I have a podcast episode from Season 2 about 車検 (shaken, car inspection) and how that seems to distort the market, at least within the expat community here, depreciating the cost of used cars. And I’ve tweeted multiple times about how used DVDs and Blu-rays seem to retain their value here while used manga and books do not.

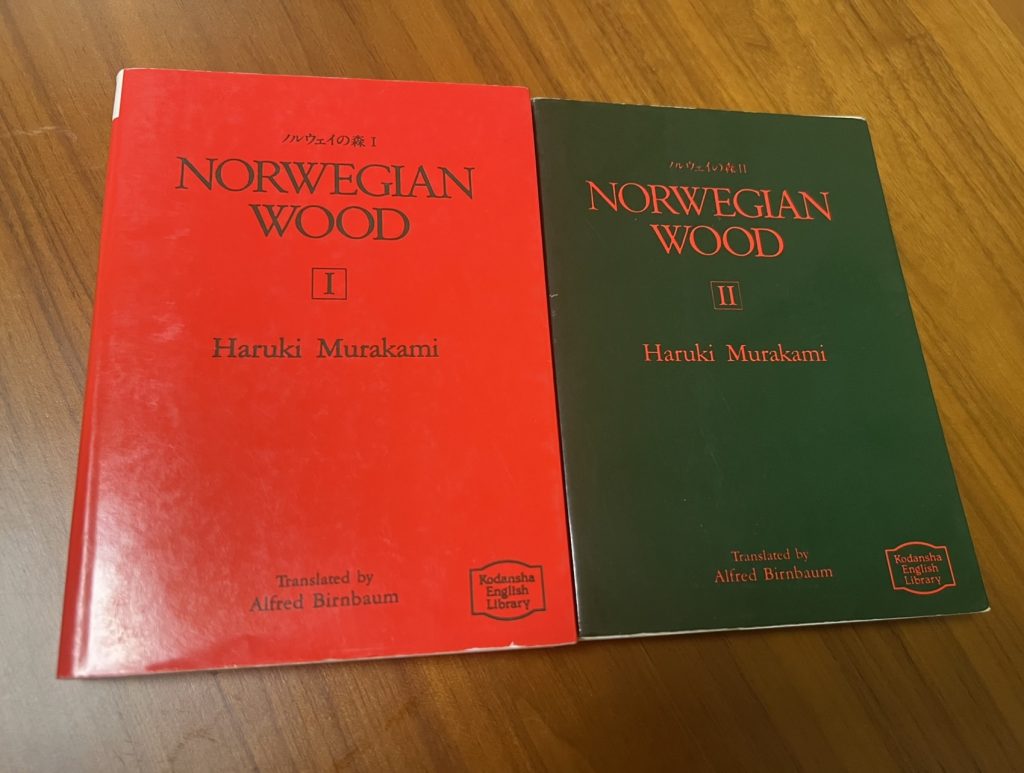

But there are upsides to this, the most recent being that I managed to buy a first edition copy of the Alfred Birnbaum translation of Norwegian Wood on Mercari for just over 2,000 yen. Last fall, on a whim, I searched to see if any were available, and a copy had sold a month prior for just 2,800 yen, which was much less than the $100 I paid on eBay for the copy I have back in the U.S. So I saved the search. For whatever reason, a few copies have popped up on Mercari over the past week. One was up for 4,000 yen, and I tried negotiating it down to 3,000, only to see the first edition get posted for less than that, so I grabbed it. (It’s a mixed pair, actually; once it arrived, I found that Part II is a second edition.)

This is the last Murakami translation that’s difficult to acquire, ever since Kodansha started reprinting the Birnbaum translation of Pinball, 1973 at some point in the late 2000s. I’m not sure whether it’s still in print, but you can get used copies on Amazon Japan for 568 yen when they used to go for $500 on eBay.

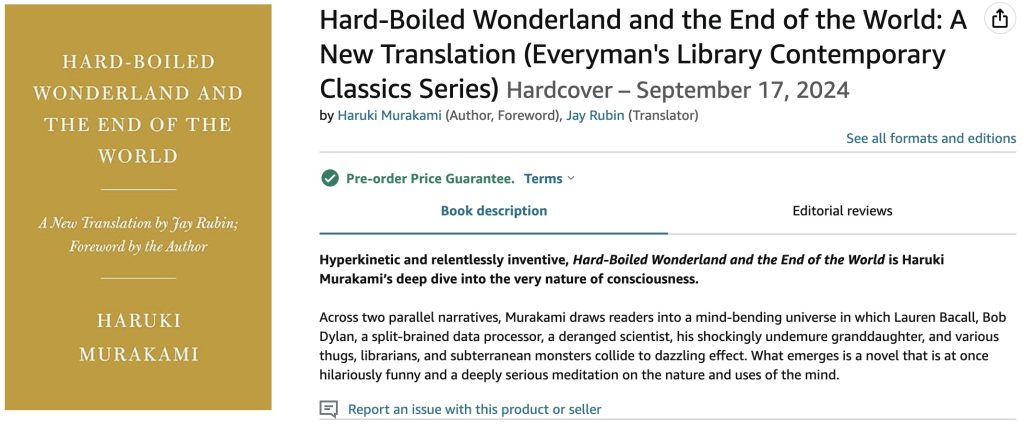

As of later this year, Norwegian Wood, Hear the Wind Sing, and Pinball, 1973 will no longer be the only Murakami novels with multiple translations. We finally have a date for the publication of the Jay Rubin translation of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World: September 17, 2024.

I can’t seem to find any announcement of this, or any information at all to be honest. In the course of looking, I did manage to track down this talk with Rubin at Wellesley, which is a fascinating look at Rubin’s thoughts on translation in general and in particular when it comes to Murakami. It deserves far more than the 900 odd views it had when I first encountered it.

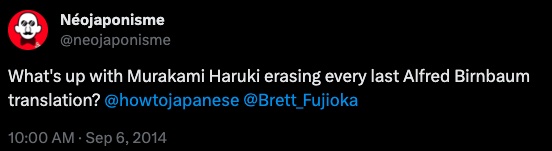

We learn a lot of information about the new translation. First, we learn that Murakami approached Rubin about doing the new translation in 2018. Which leads to the question that David Marx’s Neojaponisme asked 10 years ago:

We’ll find out more soon; Murakami wrote a foreword to the new translation. But judging from the afterword to his latest novel and how the publication process has worked for this and the translations of Norwegian Wood, Hear the Wind Sing, and Pinball, 1973, I’d say he’s looking for another version that will coexist with the original. This new version is coming out via Everyman’s Library Contemporary Classics, not from Knopf or Vintage. And as far as I know, the original translation will remain in print. (Interestingly, the link on the Everyman’s website currently takes you to a page for the Birnbaum translation.)

Murakami didn’t seek the broad publication of Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball, 1973 beyond Kodansha International because he wasn’t confident about those books. He didn’t think they were very good. I personally heard him say this at a talk with Rubin in 2003. David Karashima’s book also makes it clear that he had a break with Birnbaum at some point—I’m not sure I’d call it a falling out, but some sort of distancing when Birnbaum moved away from Japan—so it makes sense that he would go with the translator who handled his most recent bestseller (The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, 1997) when he decided to do a new, “official” Norwegian Wood translation in 2000. And perhaps he wanted a fresh look for Wind/Pinball when Ted Goosen did those translations in 2015.

This new translation of Hard-boiled Wonderland feels like a different exercise. Partly a nod to Rubin who’s always admitted Hard-boiled Wonderland was his favorite of Murakami’s novels and the singular reason he got so deep into studying and translating the writer for so long. And partly a nod to his own obsession with the novel/the lingering itch that he could never achieve what he wanted to when he first wrote it in 1985. Given that Murakami asked Rubin to do the translation before he started writing The City and Its Uncertain Walls, the two works seem to be linked, and I’ll be very curious to see when the translation of The City gets released. There’s still a chance that they are timed for simultaneous release, given that Rubin notes he submitted the translation 2-3 years ago. I do wonder what Knopf would think of that. From where I’m sitting, it feels like the ultimate marketing coup: Here, check out this new Murakami novel; oh, by the way, it’s based on the same original work as Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, so you should probably pick up a copy of that as well as its new translation so you can compare versions. But maybe publishing companies don’t think that way. Or maybe the translation of The City needs more time.

A couple other interesting notes from the talk:

– Rubin says he translated こころ as “heart” and not “mind”! This will create a very new look/feel for the work and immediately differentiate the two translations. Now we just need a version that uses “soul,” which maybe we can expect in 2065, to celebrate the 80th anniversary of publication?

– Rubin says that the use of “City” instead of “Town” in the title of Murakami’s new novel “took me totally by surprise” and made him wonder whether he should change “town” to “city” in the new translation. The talk went online in April 2023, and he says “I’m not really sure at this point.” There may have still been time for him to make those changes, but I’d be surprised if he did.

The whole talk is worth a watch. A couple of the students ask questions that obliquely hint at the question everyone seems to be asking online these days: Should good translation aim to be good English or to capture the Japanese well? (With the implication that good English misses something from the Japanese.) It’s interesting to hear Rubin’s responses.

There is a real loss here that’s important to acknowledge. Perhaps not an intentional erasure, but the result may be the same. The Birnbaum translations of Hear the Wing Sing, Pinball, 1973, and Norwegian Wood are true thrift store artifacts, so it would be a shame to see his translation of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World relegated to a similar status. He and Elmer Luke crafted such amazing voice as a translation team. I hope people hold on to them and share them with readers and students. It’s a shame that we’ll likely never see digital versions (at least not anytime soon?) that would more firmly preserve them. This is especially unfortunate given that Murakami recently put his complete catalog on the Kindle platform after a long, long wait. He seems to keep close control over how his works are distributed these days.

We will be getting access—what exactly that means, I’m not sure—to the unabridged version of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle in 2026, as Rubin donated it to the Lily Library at Indiana University, but it doesn’t seem like a given that we’ll get a full publication of it…which is a missed opportunity. (This is noted in the Karashima book.)

In the Karashima book, however, Murakami does mention wanting new translations of those early publications. If there’s an updated version of A Wild Sheep Chase announced in the next few years, that would be the sign for Birnbaum and Luke to take these updates personally. For now, though, I’d recommend running—do not walk—to Mercari to thrift what you can while it’s still there and still affordable. If anyone in the U.S. wants me to mule a copy, get in touch and we can work out a trade. And I’ll make same offer for academic libraries. Every university library with a contemporary Japanese program should have a copy of these translations on the shelves for students.

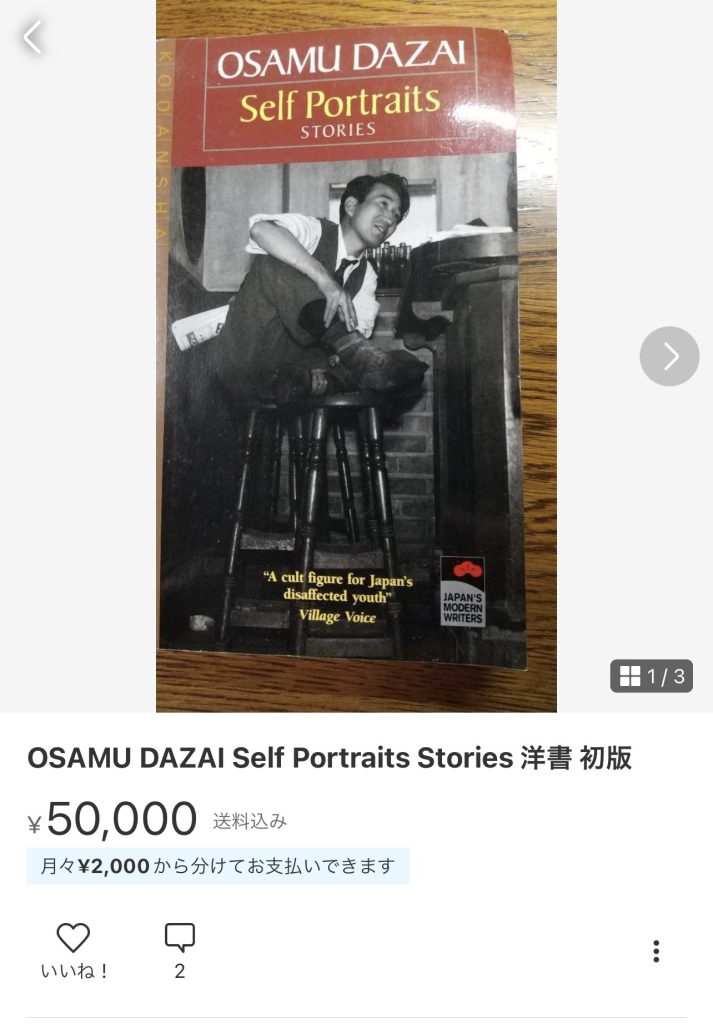

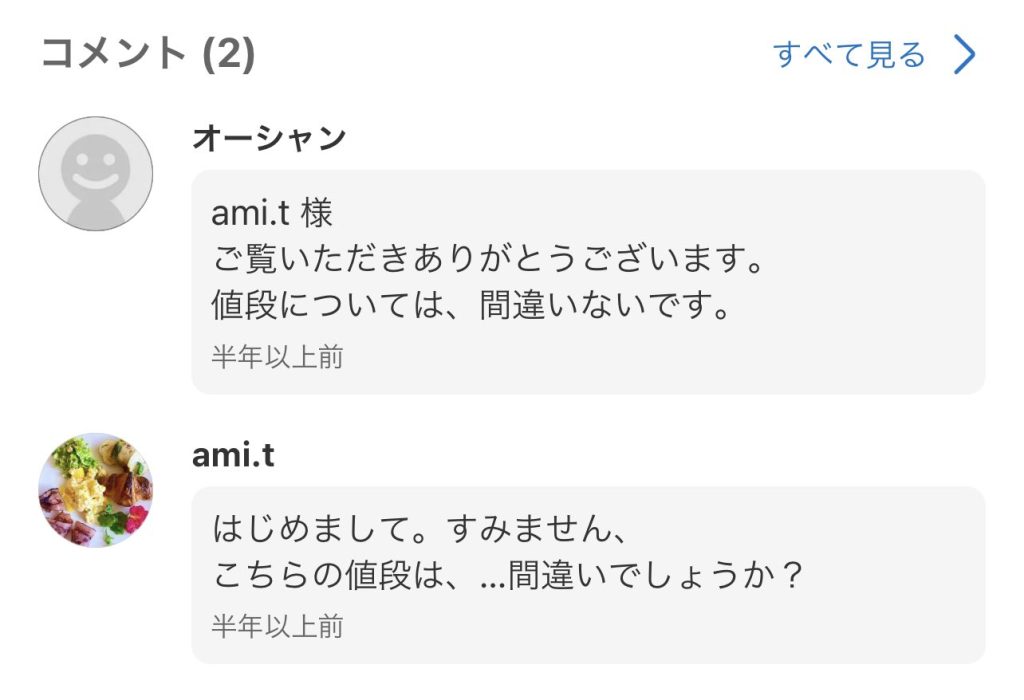

The market can be fickle. It seems to have crashed for now, at least in Japan. But you never know what buyers will want in the future, especially when you occasionally find wildly overvalued items like this collection of Dazai Osamu writing, which left even Japanese commenters baffled:

For now, though, Mercari remains a reflection of market values in Japan, and the value of printed material doesn’t hold, except in extremely rare cases, so you’ll have no trouble getting a full set of Ōwara Sumito’s 映像研には手を出すな! (Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken!) for just 3,000 yen, if not less.

Just make sure to keep control over your 積読 habits. You own the books; they don’t own you.

Check out the newsletter this month for some advice on buying appliances in Japan!