I have an article in the Japan Times today: “Complicated characters: Let us now praise difficult kanji.”

This column was inspired by two of my biggest Japanese-related realizations of all time:

1. Katakana are not inherently more difficult than hiragana.

2. Kanji are not more difficult than English words.

I think everyone comes to understand these at some point, if they study long enough, but it’s always useful to review them.

I wrote more in depth about the first a few years ago (jeez, five years ago). Students of Japanese usually start with hiragana, then go on to katakana and kanji. They learn the pronunciation of all the individual katakana, but because there are comparatively fewer katakana words, they don’t get enough reps with any to really let them sink in. Whenever they do encounter them, they end up sounding out the syllables one at a time, wondering why the script is so difficult.

By contrast, they see 勉強 so much in the first few months, that it turns into what it should be: A gestalt larger than the individual parts. The kanji are still there, if you look closely enough (and within the kanji, the strokes), but dial back your focus, and they disappear into the benkyō-ness.

My recommendation to new students of the language: Don’t learn the hiragana or katakana individually. Just start memorizing whole words. I mean, I guess you need to do them individually at some point in order to learn how to write them, but I would recommend adding large katakana words to your flashcards or SRS software immediately. カレー, ラーメン, パソコン, all of these will be far more useful than the individual katakana.

The second realization may still be up for debate. I think Japanese and foreigners who study the language both enjoy contributing to the myth that Japanese is “the most difficult language in the world.” A good portion of this myth is supported by the sheer numbers: Japanese has THREE written “languages” and there are TWO THOUSAND kanji. Saying something like English has TWENTY-SIX letters just doesn’t feel as hefty in comparison. The fact that kanji are pictographs also contributes: My god, man, they look so damn complicated! How do you even deal with a language that isn’t phonetic?

But this assumes two things:

1. Two thousand characters allow for more combinations (and more difficult combinations) than twenty-six letters.

2. Being able to pronounce a word is equivalent to knowing what it means.

1 may seem true at first, but when you consider the fact that most kanji compounds only have two characters (and the longer ones can be broken down into sets of two), whereas the average English word is 5.1 letters, the playing field levels a bit. (Based on this website which gives Japanese an average word length of over 34…clearly mistaken since it acknowledges at the top that its calculation is based on languages with spaces.)

Japanese words look like this: __ __, with roughly two thousand possibilities for each space.

English words look like this: __ __ __ __ __, with twenty-six possibilities for each space.

2000 x 2000 = 2,000,000

26 to the power of 5 = 11,881,376

Obviously, there aren’t that many words in either language, but this is just a quick calculation that can hopefully put things in perspective: English words are equally complex as kanji.

And they are also equally simple. Take, for example, antidisestablishmentarianism. When I was in 3rd Grade, this was the word to know, for whatever reason. I guess when you’re ten years old, it’s really cool to know long words that seem complicated.

At the time, it seemed like one massive thing, but when I look at it now, it looks like kanji to me. Rather than being a gestalt or a string of individual letters, I see little packets of information: anti-, dis-, establishment, -arian, -ism.

Theoretically, you don’t even need to know how to pronounce these to know their meaning. They provide a visual way to break down the word, to a certain extent (if you are familiar with them). Which is another advantage to kanji: Because the pieces contain more information in and of themselves—is it safe to say that 義 holds more information on its own than -ism?—you have an additional method to gain information from the pieces, independent of their pronunciation.

Just because we English speakers don’t spend time in school learning these packets in the same way that Japanese students tackle kanji (lots of repetition required to master the ability to write the individual units) doesn’t mean that English is easier. They just require different strategies.

That’s all well and good, you might say, but give us something prescriptive, Morales! Well, the best I can do is these two pieces of advice:

1. Start reading in context as soon as you can. This will force you to look at kanji as compounds rather than individual characters.

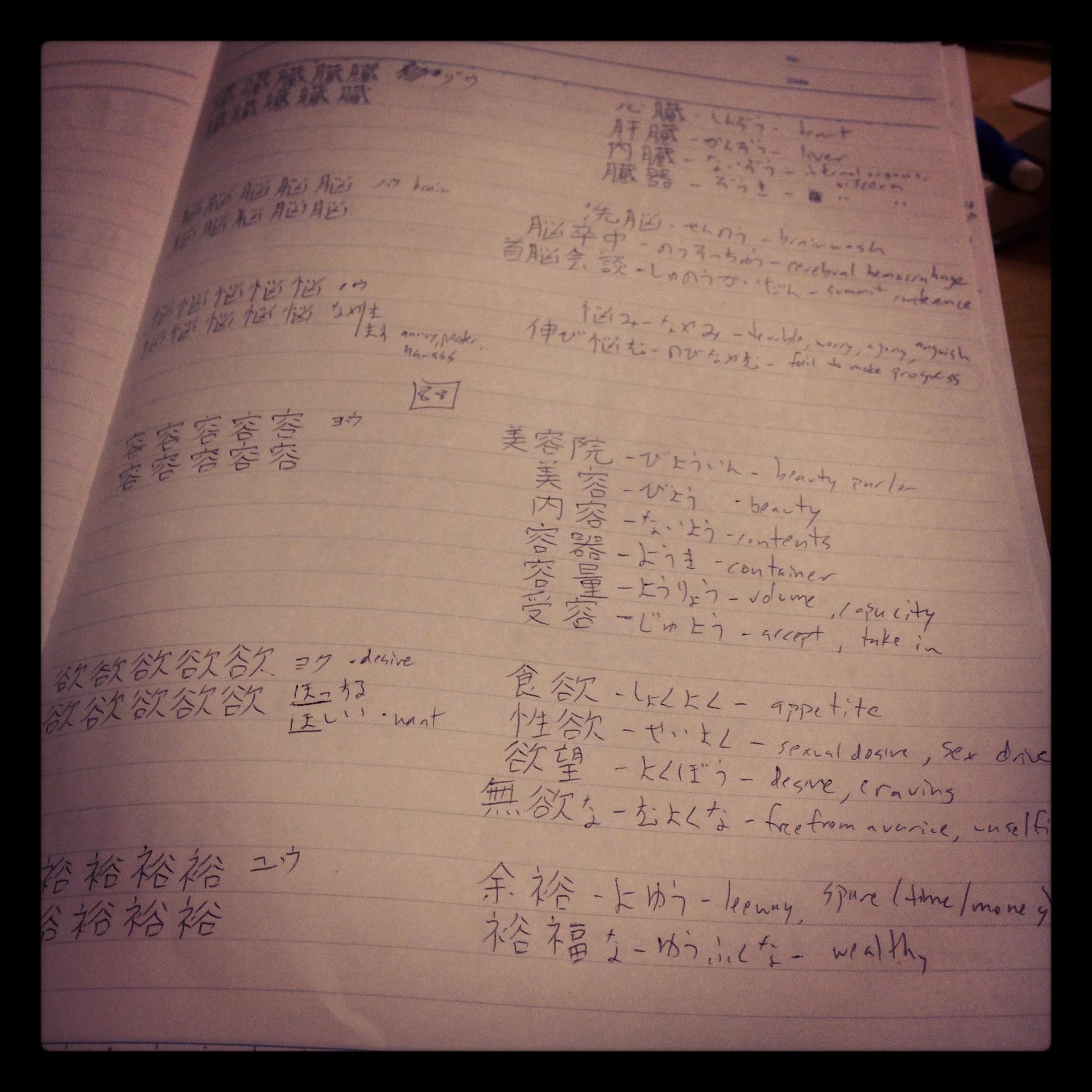

2. When you are practicing your kanji composition, practice writing compounds or short phrases rather than individual kanji. This will hopefully serve to embed the idea that the whole is more important than the parts. For an example of this, see the image at the top of the post: These are my notebooks from study for the JLPT Level 1 test.

And if you haven’t yet, you must read “Kanji as Argo,” over at No-Sword, an amazing take on studying kanji that emphasizes number 1. The money quote:

…if you were learning French, you wouldn’t refuse to look at a French book at all until you’d memorized all possible verb conjugation patterns. (If that was the standard approach, no-one would ever read any French books at all—not even the French.)