Apropos of plugging my Japanese Reading Group, which is entering its fifth consecutive year (!), and of getting in a November blog post before things get crazy with homebrew club festivals, cider brewing, and the holidays, here is my translation of the reading we did for October, a real gem of a story:

Snow Day

Kanoko Okamoto

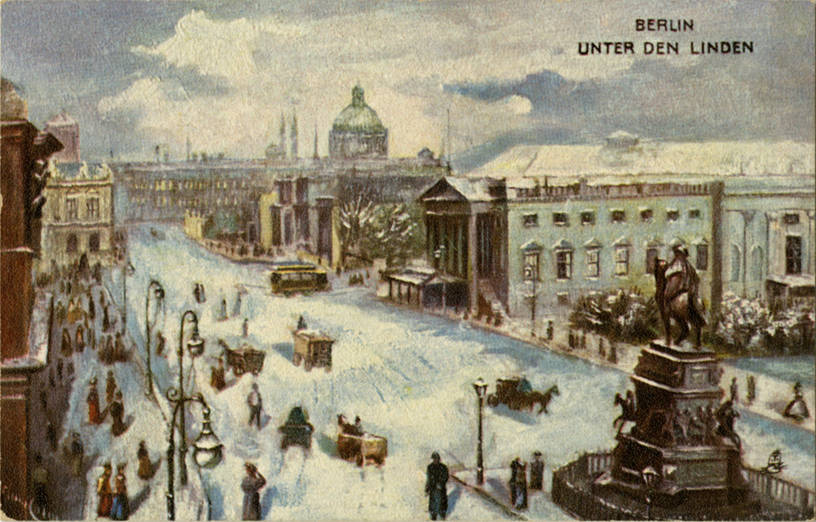

One winter we were living in a big, old apartment on Kaiserdamm in Berlin. Outside the snow was falling in waves. Inside, our heater had a large chimney that went through the ceiling, and we kept filling it with firewood. There were only rumbles from the trains and the honk of car horns; not even the dogs were barking in the midday quiet elicited by the snowfall. There was a loud knock at the door. “Who could this be with all the snow?” I thought as I opened the door. A group of three workers trundled in, made up of a young man, a middle-aged man, and an old man.

“We’re here to fix the electrical lines.”

They were all quite friendly looking. I hadn’t expected them, so I was taken aback for a moment, but I quickly came to my senses and showed them inside. I came to like the workers in Berlin soon after arriving there (I got to Berlin at the start of summer). Most of them were cheerful and had a true naïveté. I don’t know how many times I saw workers packed into the back of a truck smile and wave at us foreigners as they passed by. These lovely people had willingly taken on a working life, so whenever presented with the opportunity, we treated them with kindness and never for a moment behaved with the caution typical of some foreigners. At first glance, the workers’ clothes seemed disheveled, but when I looked closer, it was clear they had fastidious German cleanliness—that is to say, their wives or daughters had done an excellent job of washing them and patching them back together.

They finished the electrical repairs. I could see from the window that the snow was still coming down outside. When I offered them a fur rug, they sat down without protest and faced the heater. Unfortunately our maid caught a cold two or three days earlier and had taken off work. My husband the whole time was in the far room, completely absorbed in cartoons he was working on to send to Japanese newspapers. I made tea on my own and offered it to them.

“I’ll get you some cigarettes, Japanese cigarettes,” I said and started to get up to get some Shikijima cigarettes from my husband.

As I did, the middle-aged man said, “We don’t need cigarettes, miss. [Westerners have a tough time telling how old Asians are.] Instead, sing a Japanese song for us.”

“Do you sing songs in Japan, miss?” the old man asked in such a gentle way.

I adjusted the way I was sitting and granted their request right away. I had everyone close their eyes and I sang “Katyusha” in Japanese style without letting my voice quiver. The young man said it was Russian style, which impressed upon me Germans’ nature as a people of music. Next, to prove I could sing a truly Japanese song, I sang, “Quickly, quickly quickly, up and over the waves!*”

The middle-aged man complained again: “Miss, that sounds like a men’s college song. We wanted a Japanese woman’s song…something you yourself might usually sing.”

Ah, of course, I thought to myself, and then, with a renewed focus, I sang for them in an unadorned tone: Sakura, sakura, across the spring sky, as far as the eye can see. Is it mist or clouds? Fragrant in the air. Come now, come now, let’s go and see them*.

They stood up happily and praised the elegant, sweet melody. “We’ll tell all our buddies,” they said, complimenting me as they slung their tools over their shoulders. Then they glanced out the window at the snow that continued to fall and fall so evenly and headed for the door. Until—

The young man who had been silent to that point stopped and turned to me with a look of pleading in his eyes.

He said, “Could I have a stamp? Just one Japanese postage stamp. I collect them from around the world.”

I peeled off several stamps from the envelopes of letters dear to me that had arrived from home and placed them into the palm of his poor hand, gnarled and rough from an intense life of labor.

This is such a well constructed short. It starts and ends with vivid images—the quiet of snow-covered streets, filling the stove, the chimney piercing the ceiling (which must’ve been so striking for Japanese at the time), peeling off stamps from letters, and the final zoom into the worker’s palm.

Okamoto is a strangely intertwined figure. Her brother studied with Junichiro Tanizaki, she was close with Yosano Akiko, she married a famous cartoonist, and her son was Tarō Okamoto, a famous artist known for the Tower of the Sun. Sadly she died at 49 of a brain hemorrhage and most of her works were published posthumously.

Check out the other readings for our reading group here, and feel free to contact me about joining us (we meet online via Google Hangouts) the second Tuesday of each month at 6:30 CST.