Year 1: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year 2: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year 3: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year 4: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year 5: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year 6: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year 7: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year 8: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year 9: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year 10: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year 11: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year 12: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense, Rotemburo

Year 13: Murakami Preparedness, Pacing Norwegian Wood, Character Studies and Murakami’s Financial Situation, Mental Retreat, Writing is Hard

Year 14: Prostitutes and Novelists, Villa Tre Colli and Norwegian Wood, Surge of Death, On the Road to Meta, Unbelievable

Year 15: Baseball on TV, Kindness, Murakami in the Asahi Shimbun – 日記から – 1982, The Mythology of 1981, Winning and Losing

Year 16: The Closet Massacre, Booze Bus, Old Shoes, Editing Norwegian Wood, Prophecy

Year 17: Athens Marathon 1987, Infinite Appetites, Black Monday, Vibes-cation

Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

The final week of Murakami Fest 2024.

This next chapter, ペトラ (Petra), is a bit of a return to form. It’s a few pages longer than the previous chapters and Murakami hits the ennui notes that he’s been going for over most of the book, painting a subtle, muted portrait of offseason travelers taking things as they come in Europe.

After exhausting the sights in Mitilini, they take a bus to Petra where they take a room with a family through what may be the Women’s Cooperative of Petra. Murakami refers to it as 農業婦人会 (Nōgyō fujin kai, women’s agricultural association). They have lunch at a restaurant, see an uzo distillery, buy postcards, have coffee, watch the sunset, and then return to their hotel room where Murakami drinks brandy and reads Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Not a bad way to spend the vacation.

It’s a nice chapter, with a few delicate portraits of the people they run into. Here’s how he ends things:

“You’re Japanese?” she said. “I met a lot of Japanese in Australia. They’re a clever people.” She shook her head sadly. Then she gazed out past the fields, almost like she could make out Australia just past the horizon. “Visit again sometime,” she said. “It’s quiet here. Next time you can take it easy.”

We will, I said. We want to visit during the summer next time.

“You don’t have children?” she asked, like she’d suddenly remembered.

We don’t, I responded.

She looked at us and then smiled. “But you’re still young.”

We packed our things and paid the bill. She seemed very embarrassed to take the money. I don’t know why. Maybe she hadn’t yet adjusted to working with customers like that. I gave her some coins from Japan and told her it was for the girl who had shown us the way. She thanked me and stared at the coins in her palm. “Sayonara,” we said. Then we left her behind in her silent, puddle of sadness.

That’s everything that happened in Petra.

「日本の方ですね。オーストラリアで沢山日本の人見ました。クレヴァーな人達」そして彼女は哀しげに首を振る。それから畑の向こうの方に目をやる。そのむこうにオーストラリアが見えるかしら、という風に。「また来て下さい」と彼女は言う。「ここは静かでいいところです。今度はゆっくりと来てくださいね」

そうする、と僕らは言った。今度は夏に来たいものですね。

「お子さんはいらっしゃらないの?」とふと思いついたように彼女は尋ねる。

いない、と僕らは答える。

彼女は僕らの様子を見て、それからにっこりと笑う。「でもまだお若いですものね」

僕らは荷物をまとめ、勘定を払う。お金を受け取る時、彼女はとても恥ずかしそうにする。どうしてかはよくわからない。まだそういう客を相手にする仕事に慣れていないのだろうか。僕は案内してくれた女の子にと言って日本から持ってきた小銭をあげる。彼女は礼を言って、手のひらに乗せたその小銭をじっと見る。「さよなら」と僕らは言った。そして彼女をその物静かなみずたまりのような哀しみのなかにそっと置き去りにした。

それがペトラの町で起こったことの全てである。 (310)

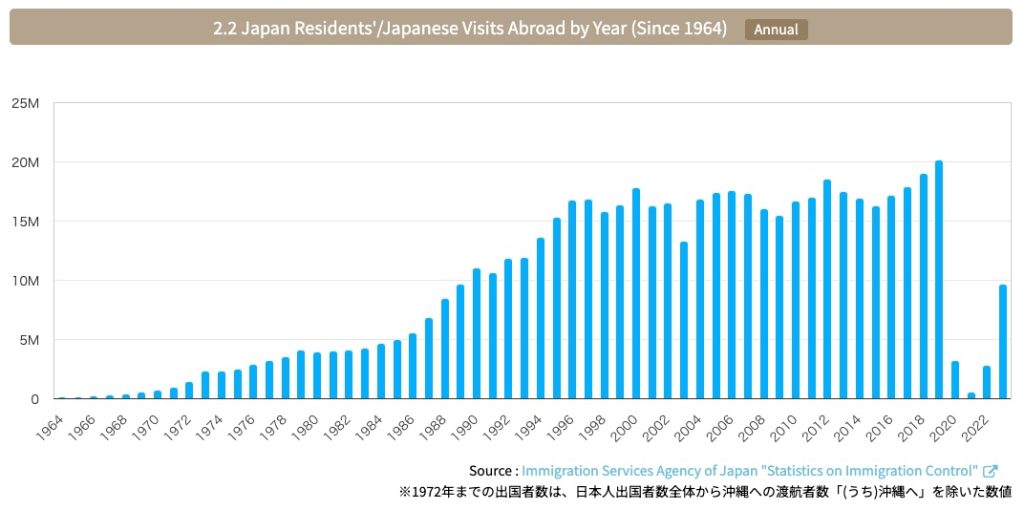

It’s starting to become more apparent that this is Bubble Era Japan. Obviously, the whole book is premised on this fact. Murakami, a mid-tier writer with a small but dedicated readership, could afford to close up shop in Japan, giving up many if not all of his regular writing gigs (one of the main points of the trip), and move to the Mediterranean for three years, living on a restricted budget. Room and board is 1,800 yen for the night and 500 yen for breakfast for two. Dinner for two is 1,300 yen and includes fish, salad, and wine. This only works if the yen is super strong. I’m sure that Norwegian Wood’s runaway success changed the equation a little, but it doesn’t seem to have hit yet. Something to watch for in coming chapters.