I love browsing Japanese bookstores. I come from a family of consumer addicts, so part of the reason is the thrill of being in the position to potentially make a purchase. The other part of it, which I miss a lot these days, is gradually getting to know more about the Japanese literary world.

I took the basic literature classes in college and have been trying to get to know writers better through my Japanese reading group, but you don’t get a sense of the living, breathing 文壇 (bundan, literary world) in the classroom. You have to get out there and see what’s on the shelves and, in particular, in the magazines.

Japan has a pretty decent selection of literary magazines that are all relatively available, especially when compared to the United States. I’m currently in Chicago, the third-largest city in the country, and I have no idea where I would go to get a literary journal. I’m sure I could find out pretty easily, but I’m also certain it would involve an hour’s worth of round-trip travel to and from the bookstore, and that there are probably only a small handful of bookstores where I could find them. Obviously the New Yorker is everywhere, and The Atlantic is also readily accessible, but anything beyond that is going to be a tough find, even something like Harpers.

In Japan, on the other hand, I lived within a 10-minute walk of two bookstores that had just about any magazine available, and I didn’t live near a major train station. There are dozens of bookstores where you could find Monkey Business, and even more where you can get some of the mid-tier publications like 小説すばる (Shōsetu subaru) and other magazines.

I learned about the writers by trial and error, really. You do some 立ち読み (tachiyomi, stand and read) to find something that looks good, make a purchase, and then look for that writer’s name elsewhere if you enjoy it. Recommendations from bookstores and libraries and friends helped, but so did browsing the fold-out 目次 (mokuji, index) at the front of magazines.

There’s something special about that 目次. Generally the cover of a magazine will include some of the big names in the issue, but I found it a fun challenge to try and spot other writers here and there on the folded out index. I was always excited to see 綿矢りさ (Wataya Risa) or 金原ひとみ (Kanehara Hitomi), authors of the first two novels I read in Japanese, or 三崎亜記 (Misaki Aki), who was a personal favorite.

After having been back in the U.S. for nine years now, I was pleasantly surprised to see none other than 村上春樹 (Murakami Haruki) in the June 2019 issue of 文藝春秋 (Bungei shunju) when I was in Japan on business earlier this month.

文藝春秋 is one of the big dog magazines that selects the Akutagawa Prize twice a year. It’s fairly conservative, and Murakami was never selected for the Akutagawa Prize when he was younger (and not as well accepted by the literary establishment). Murakami published stories in 文学界 (Bungakukai), also published by the 文藝春秋 company, pretty quickly (including the very early novella 街と、その不確かな壁), but his first fiction in 文藝春秋 itself didn’t come until the 1990 story “Tony Takitani.” (He did have interviews, essays, and critical writing published there…including a piece about translating Paul Theroux and an interview about the success of Norwegian Wood.)

(As always, Yoshio Osakabe’s now defunct Geocities website is a great place to track down obscure Murakami articles and interviews from the 80s. You can access the cache through Archive.org. See this link.)

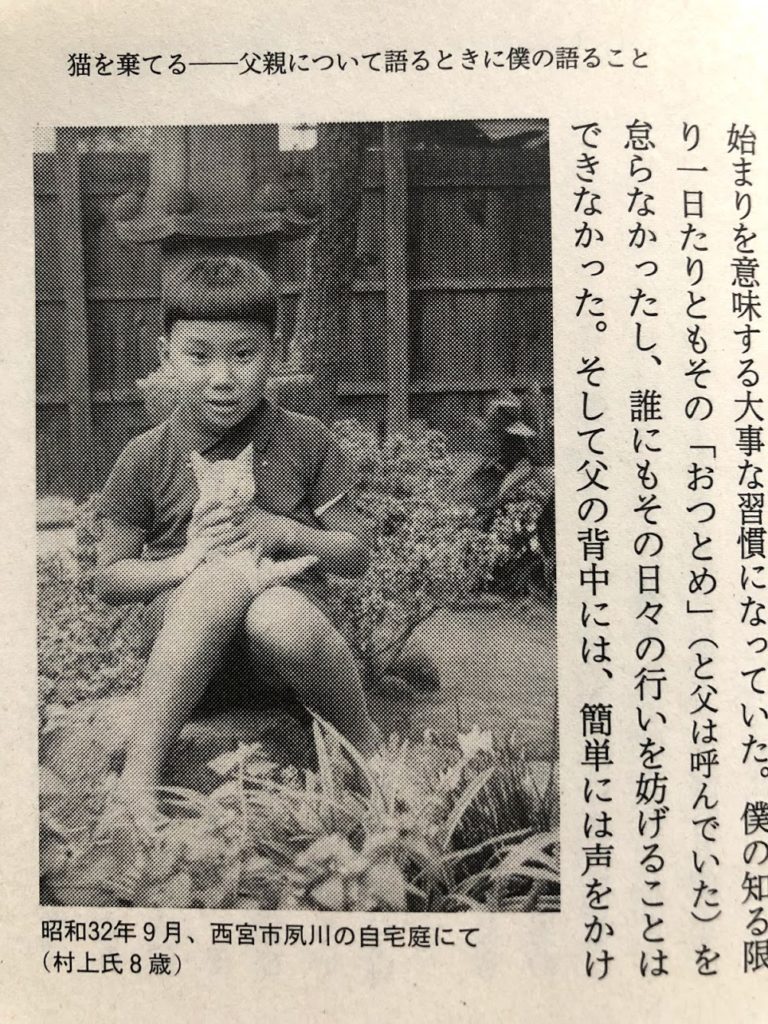

Murakami has a nonfiction piece titled 猫を捨てる−父親について語るときに僕の語ること (Throwing out a Cat – What I talk about when I talk about my father), and it’s the best thing I’ve read by him in a long, long time. It’s 25 pages, so pretty long, but not long enough for the magazine to advertise the 枚数 (maisū, page count) from the manuscript on the cover, which I believe is usually given in terms of 原稿用紙 (genkō yōshi, “official” manuscript paper).

The story starts and ends with stories about cats and Murakami’s father. I won’t spoil them because they are worth seeking out (although you can surmise the content of one from the title), but they create the very typically Murakami sense of mystery within reality.

Murakami’s father was the second of six sons to the priest of Anyōji Temple in Kyoto. When Murakami’s grandfather was hit and killed by a tram, there was a discussion amongst the family about who would take over the temple. It had to be one of the four sons remaining with the family (two had been sent off as adopted children to other temples and had changed their names).

The 長男 (chōnan, oldest son) ends up taking on that responsibility, but nearly all of the six sons had received education as priests, and Murakami’s father had even been sent away to a temple to be adopted until he got sick from the cold in Nara and was sent back home. Murakami nicely weaves this story of his father being “thrown out” in with the cat and the sense of generational trauma that he imagines his father must have later experienced during the war.

His father didn’t talk about the war very much, and Murakami admits that he didn’t resolve to look into the details until five years after his father’s death and that for a long time he didn’t want to because he was under the impression that his father’s division had participated in the Nanjing Massacre.

It turns out, Murakami’s father’s timing was extremely fortunate. He was conscripted three times into the 16th Division and released all three times after a term of service. He joined after the division participated in the Nanjing Massacre and was discharged twice, once in August 1939 and then again in November 1941 after only two months. Murakami wonders whether his father would have been discharged that second time—allegedly by a friendly officer who thought he would serve the country better as a student—after Pearl Harbor, just a month later. The division was quickly sent to the Philippines and ended up being almost completely decimated there.

Murakami includes haiku his father wrote and sent from the battlefield. I won’t try and translate or interpret them, but this one is interesting and draws in his religious background:

兵にして僧なり月に合掌す

Despite his father’s lucky timing, he still encountered the realities of the brutal war. Murakami recalls the only conversation they had about it in which his father described how Chinese prisoners were executed by decapitation.

He then transitions to life after the war. His father gave up studies and became a teacher after Murakami’s mother became pregnant. He wasn’t happy with his life, he drank and was difficult, but Murakami never directly experienced any harm from this. They did have a falling out, which Murakami describes in more depth than I can remember seeing in the past. Yet he still seems to hold back—the specific disagreement is never described:

そのような父と子の葛藤の具体的な側面については、僕としてはあまり多くを語りたくないので、ここではごく簡単に触れるだけにする。細かく話しだすとかなり長い、そして生々しい話になってしまうから。でも結論だけを言うなら、僕が若いうちに結婚して仕事を始めるようになってからは、父との関係はすっかり疎遠になってしまった。とくに僕が職業作家になってからは、いろいろとややこしいことが持ち上がり、関係はより屈折したものになり、最後には絶縁に近い状態となった。二十年以上まったく顔を合わせなかったし、よほどの用件がなければほとんど口もきかない、連絡もとらないという状態が続いた。

I personally don’t want to get into the details of the dispute between a father and child, so I’ll just touch upon it briefly here. If I were to go into the details, it would end up being a long and raw story. But to sum it up, I married young and once I started working, I was almost completely estranged from my father. In particular, once I became a working writer, a lot of complicated issues came up, which twisted our relationship even further, and in the end we had nearly broken off relations. We didn’t see each other for 20 years, and unless there was a significant issue, we continued not talking or communicating.

Murakami writes nicely about this generational divide:

おそらく僕らはみんな、それぞれの世代の空気を吸い込み、その固有の重力を背負って生きていくしかないのだろう。そしてその枠組みの傾向の中で成長していくしかないだろう。良い悪いではなく、それが自然の成りたちなのだ。ちょうど今の若い世代の人々が、親たちの世代の神経をこまめに苛立たせ続けているのと同じように。

Perhaps all of us breathe in the air of our own generation and are forced to live with the burden of its inherent gravity. And we are forced to grow within the trends of that framework. It’s neither good nor bad, it’s just the natural way things come about. Just as the younger generation today continue to earnestly fray the nerves of their parents’ generation.

One other thing of note is that Murakami admits to dreaming! He says his father’s dissatisfaction with his grades growing up has left him with stress dreams:

今でもときどき学校でテストを受けている夢を見る。そこに出されている問題を僕はただの一問も解くことができない。

Even now I occasionally have dreams in which I’m taking a test. I’m unable to solve even a single problem of the questions being given.

Murakami has famously claimed that he doesn’t dream (in a New York Times interview amongst other spots). But he’s also claimed that he’s never been hungover, which seems like a stretch.

At any rate, this is a good piece and worth reading. It’s certainly better than Killing Commendatore, which also happens to address the Nanjing Massacre. Perhaps that’s what drew it to Murakami’s attention, although from his telling, he has been looking into his father’s war history since 2013, well before KC was published.

And if you’re not reading Murakami, you should get out there and scan some 目次 for things you are interested in reading. Do enough repetitions and you’ll start to find the names more familiar and likely some pretty interesting literature.