I was in the Japan Times twice recently.

The first is an extended look at いい歳 (ii toshi, decent/sensible age), which I initially examined in my May newsletter: “What exactly does it mean when someone tells you to ‘act your age’?”

And for the second, I mined a survey from a comedy site and a Quora question about the funniest Japanese words: “‘PPAP,’ ‘golden jewels’ and other words that make the Japanese giggle.”

I’ve been putting off this post because I’ve had my hands full the last month traveling, translating, writing, and catching up on ye olde podcast, but I was inspired to get something in shape after seeing this tweet:

I was a little surprised by how much hate it was generating. Yes, I get that “Zoom harassment” (making fun of someone’s room during a Zoom call) and “blood type harassment” (deciding someone will act a certain way based on their blood type) are ridiculous. They are evidence of annoying coworkers.

But two of the others seemed to have more potential for actual harassment, at least based on the U.S. definition. The “confession harassment” in particular seems to present potential overlap with sexual harassment. A lot of the replies in the thread don’t seem helpful:

“Try it, the worst she can say is no”

“Imagine getting shut down by your crush but then you’re also guilty of harassment”

Even if these are jokes, they aren’t good looks!

Not that you absolutely can’t date someone at work, but unwanted attention can absolutely become harassment.

いい年 makes an appearance under “age harassment,” which isn’t the typical “age discrimination.” I thought I explained convincingly why いい年 likely disproportionately affects those who already face so much harassment at work. The best response when asked any questions like these is often, “What do you mean by that?” Generalizations will generally fall apart under scrutiny like this.

And I’ll briefly mention here something I didn’t have the space to get to in the article about the funniest words: There were a lot of country names included in the list, which made me feel kind of meh. There’s nothing less funny than laughing at “foreign” sounds just because they sound foreign to you.

At any rate, Happy Tanabata, y’all!

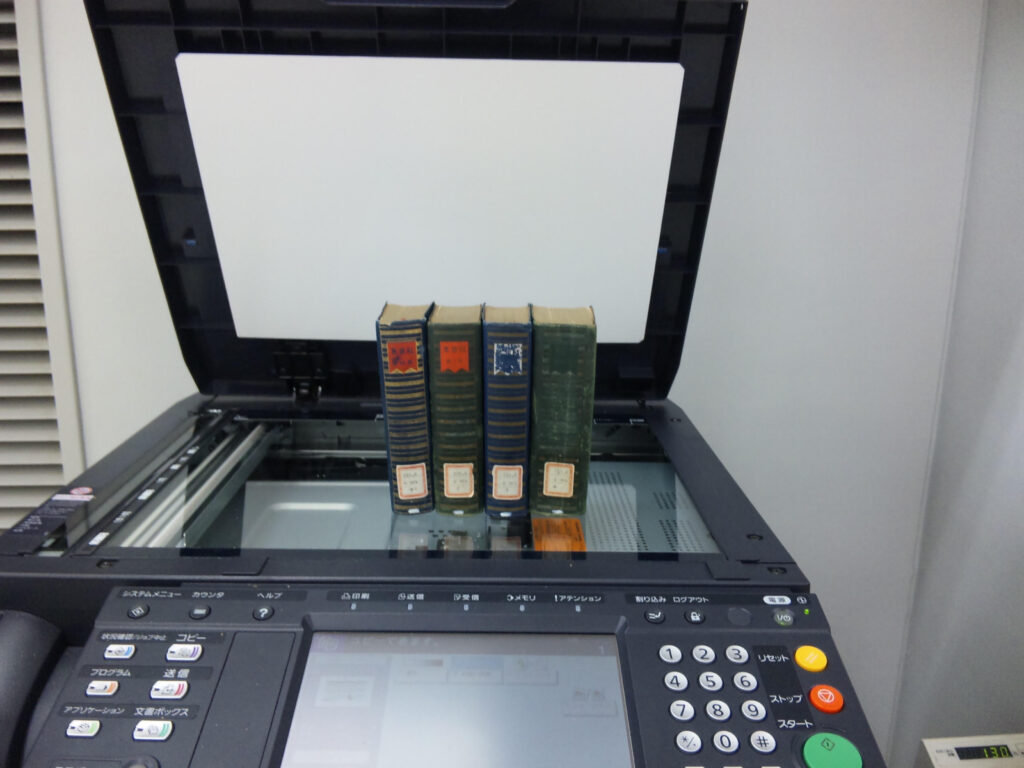

Courtesy of Molly, this is a photo of Ozaki Kōyō’s four-volume 紅葉集 (Kōyōshū), pub. Shun’yōdō (春陽堂) 1909 and how one who access the original text (in its original binding!).

Courtesy of Molly, this is a photo of Ozaki Kōyō’s four-volume 紅葉集 (Kōyōshū), pub. Shun’yōdō (春陽堂) 1909 and how one who access the original text (in its original binding!).

Brian Epstein is a patent attorney with

Brian Epstein is a patent attorney with