The newsletter is out! And the podcast is here for you as well. Check out how to add なんです to your active vocabulary. My tourist recommendation this month is the city of Beppu. Summer is not really the time for onsen, but we can dream of crisp autumn days.

Category Archives: podcast

Collector’s Mindset

I just sent out the February newsletter and podcast. This month I wrote about a phrase I encountered last summer while prepping for my annual Murakami fest. Give it a listen here:

You can see the blog post for that entry here.

One of the phrases really stuck out to me, and it’s one that I’ve tried to incorporate into my active Japanese: あとになってわかったこと (Ato ni natte wakatta koto). I won’t translate it here. Click over to the newsletter to see my explanation. Or better yet, listen to the podcast and hear how I’ve been able to take this phrase and expand it into other usages and patterns, nearly all of which I’ve been able to confirm examples for. Pretty neat, especially since they are patterns that I’d never heard before but was able to construct on my own. This is, essentially, how you learn a foreign language. Imitation, adaptation, and eventually creation. You can confirm your new creations by comparing with other examples online, like the blog post from a new father I found.

In the newsletter I’ve also got some strategies about how to best develop your eye and ear for sentences that are interesting, helpful, and useful.

The hardest part is realizing that a sentence is interesting, but the next hardest step (which is basically just as difficult) is to then prompt yourself to write it down to peruse in the future with the goal of increasing exposure. You’ve got to do both.

__

And I’m glad that I didn’t forget to share the link for this great (and very extensive) Wikipedia page: 最長片道切符 (saichō katamichi kippu). Can you parse that from the kanji alone? It’s three two-character compounds lumped together, and I bet if you take them in reverse order you can figure it out pretty easily.

At any rate, that’s the Wikipedia page that inspired my interest in the book I’ve been reading lately, which I talk about in more depth on the podcast. Fortunately for me I was able to escape the gravity of my Mercari 積読 addiction and get these pages off the shelf and onto my eyeballs. Keep that pedal pressed.

__

On a quick closing note, please do check out my call for comments and opinions at the end of the newsletter. I’m curious to know what readers and listeners are thinking. Do you like having the monthly newsletters mailed to you? Do you prefer that over a blog-style publication? Are you reading both the newsletters and blog posts? If I shifted to a different newsletter platform, would you be willing to read there or do you prefer Substack?

I like the balance between the newsletter and blog with more casual, off the cuff posts here and more feature-style writing on the newsletter, but it would be nice to have more control over the platform (and Substack has some pretty obvious issues). I spent a weekend looking into Ghost as a potential option, but it does seem making a switch would mean taking on another monthly bill and potentially a good amount of tech work (if I were to self-host). I’d love to hear what you think, and if you listen to the podcast I go into a little more details about the tech side of things. If anyone has any experience or thoughts on that side of things, I’d love to hear from you.

The City and Its Uncertain Walls – Review Redux

The English translation for Murakami Haruki’s latest novel The City and Its Uncertain Walls will be published on November 19, and reviews are starting to trickle out, so I thought I’d re-run the review episode of the podcast I put online after reading the Japanese version when it was published in 2023.

I added about 20 minutes of content as an introduction taking a look at two negative reviews (The Guardian and the Financial Times) and one positive review (The Telegraph) along with two interviews (The New Yorker and NPR). I’ll keep an eye on others as they come out and will probably do a quick look at some of them on the next episode of the podcast or in the newsletter this month, but I don’t think I’ll be reading the translation myself. I’ve spent enough time and money on that book.

Check out my full review on Medium and additional comments on the newsletter last year.

The Various Forms of うかがう

The newsletter and podcast are online:

This month, the core topic I looked at was how easy and broadly useful is 伺う (ukagau) is, especially for folks struggling to gain a handhold with keigo: This is your handhold.

伺う means so many different things at once: to listen/hear, to ask, to visit, and to detect/view. There are a number of set phrases that you should start to memorize, and once they become more familiar, you’ll hopefully find yourself reaching less frequently for more complex verb permutations, which gives you more time to become familiar with those complex verb permutations, making them more familiar and less complex, enabling you to reach for them more easily…it’s a cycle, and you just need a way in.

However, 伺う is more complex that it may first appear, likely because of how broadly it can be used. There are actually (at least) three different kanji that get used for うかがう.

The first and most frequent is 伺 which gets used for those core meanings above.

The two additional kanji take on these meanings:

窺う

「そっと(気づかれないように)様子を見る」という意味

“To secretly watch (so that you aren’t noticed”

Kenkyusha also lists several other definitions: to peer into/through something, to watch/wait for an opportunity, to infer/surmise. So it appears as those this meaning can be rather broad as well and loses some of the deference in the other definitions.

覗う

「何かを通してのぞいて様子を見る」という意味

“To peer through something”

While 窺 can mean “peer into/through” something, this kanji tends to take on more of those meanings because it’s also associated with the verb のぞく (nozoku), which is the more frequently used word for “peek/peer” and gets used with compounds like 覗き穴 (nozokiana, peephole).

Kanjipedia also notes that 候, 偵, and 覘 are also used in various situations with うかがう, but judging from my cursory searches, these are less frequently encountered.

I think the best way to understand these as a whole is to think of all these additional kanji as (most likely) an extension of the “view/detect” definition in intricate different ways that writers can choose to take advantage of. I imagine that うかがう gets used in hiragana form pretty regularly as well, so keep an eye out for that as well.

Airbag Expressions – 確認

This month in the newsletter I wrote about 確認 (kakunin), a really useful word in so many different ways. Give the podcast version a listen here:

While writing the newsletter, I realized that 確認 can absolutely be used as an エアバッグ表現 (airbag hyogen, airbag expression). I haven’t written about this topic in a while, but I did many, many years ago when I was first getting the blog going. One of my college professors used to teach these phrases as a way to lead into a request. Given that requests require the use of social capital and there are many different levels of social interaction in Japan, it’s easy to mess up a request and/or shock someone by making a sudden request. However, if you use an airbag expression to deploy a linguistic airbag before making the request, you’re much more likely to be successful and prevent any “injuries.”

Over time I’ve started thinking about this more broadly. How can you prepare someone for what you are about to say? How can you improve the odds that you will be understood? What pieces of language enable a conversation partner to predict what you’re going to say next?

確認 is one of these magical words. Just utter 確認したいですが (kakunin shitai desu ga) and you’ve created a template for the conversation to come. Your conversation partner can clearly see what’s up the road, and all you have to do then is populate that road with the question that you’re trying to answer. Your partner will then guide you the rest of the way by providing the answer to what you’re looking for.

I’d forgotten that I wrote about this on the blog (and in the Japan Times) a long time ago as well, but I don’t think I’ve been able to put this idea into words as effectively as I have been above.

How much did Norwegian Wood weigh?

In the newsletter this month I did a check-up on my kanji study. The prognosis? DOA.

I haven’t done a serious kanji repetition for over a year now. I don’t regret the two years I spent using an Anki deck to go through the 常用漢字 (jōyō kanji, ordinary use kanji), but I do wonder whether daily writing in a journal from the very beginning of my studies—23 years ago this summer—would have had a bigger benefit. Just write! Write every damn day! Write any kanji you know, not with the goal of learning more (which you’ll do naturally if you’re in a college course, or on your own separately through dedicated kanji study), but with the goal of creating your own, organic system of repetition.

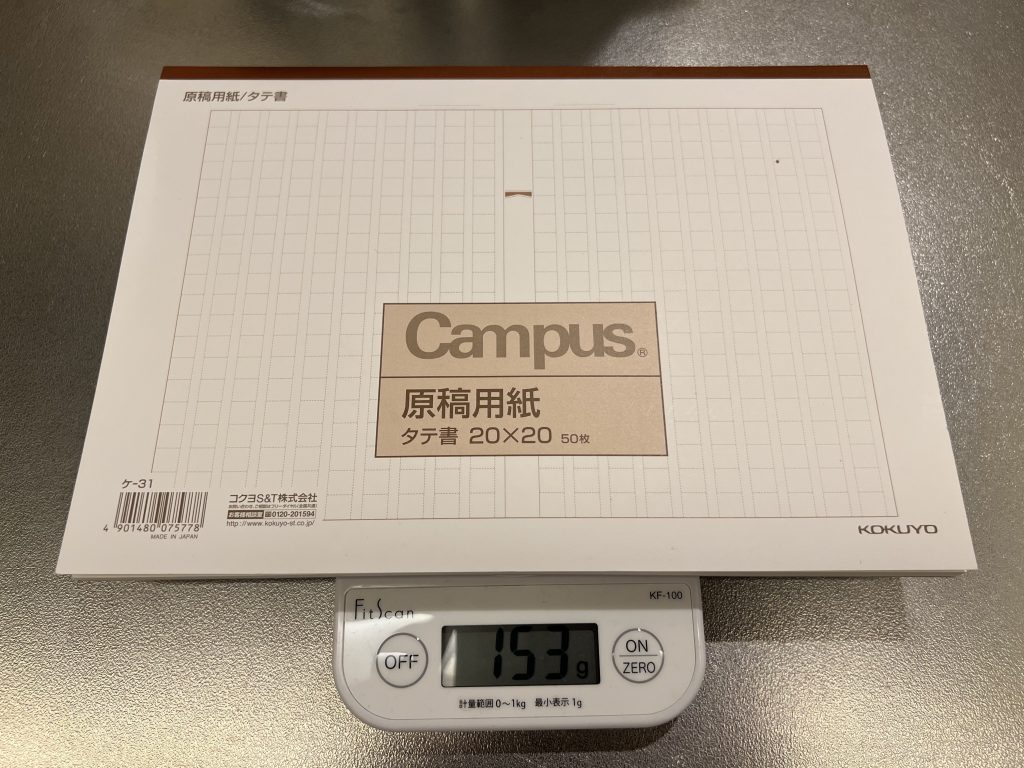

One of the main motivations behind this practice, which I did for a few months last year before a trip home in November, was to buy some cool 原稿用紙 (genkō yōshi, manuscript paper) notebooks, the same kind that Murakami used when he was writing his early novels, including Norwegian Wood.

Thanks to his book 遠い太鼓 (Distant Drums) which I’ve been slowly reading through over the past few years, we know a lot of detailed information about Murakami’s process of drafting and editing Norwegian Wood. We know that it was 900 manuscript pages; that he finished a draft on March 7, 1987, in a marathon 17-hour writing session in Rome; that the next day he started writing out a second draft of the novel; and that he completed the revision/redrafting process on March 26. This means that on March 26, he was in Rome with at least 1,800 manuscript pages.

The notebooks I’ve been using have 50 pages each, which means that this would have been 36 notebooks if Murakami was using something similar. Each one of these notebooks weighs 153 g, which means that the 36 that Murakami was lugging around could potentially have weighed 5,508 g or 5.5 kg = 12.14 lbs, which the internet tells me is about the same weight as four human brains. In a more useful comparison, this is about the size of one slightly larger than average cat.

So Norwegian Wood doesn’t quite meet chonk status, especially when you divide the two drafts in two to get the 6.7 lbs that Murakami delivered personally to a Kodansha employee at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair.

Color me a little surprised. I never knew you could fit so much on a single manuscript page. Even The Wind-up Bird Chronicle was only 2,500 pages total, according to the internet, which means it would have weighed 7.65 kg = 16.87 lbs. A bit chonkier to be sure.

Fortunately for Murakami, he switched to a word processor well before that novel, so he would not have needed to lug notebooks around the U.S. as he was writing.

Check out more on kanji and notebooks in the podcast this month:

The State of 文芸誌

The newsletter is online, which means so is the podcast:

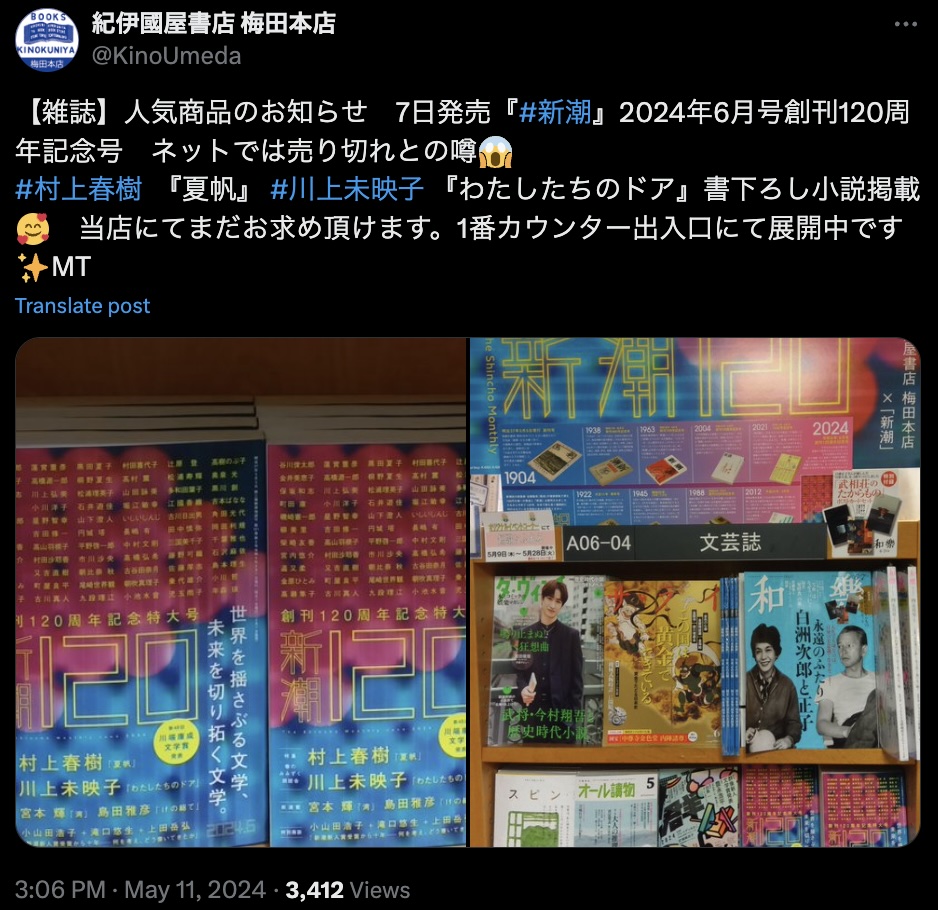

This month I wrote about the 文壇 (bundan, literary world), which is most easily accessible in monthly literary journals. These journals have somehow survived in print, unlike just about every literary journal in the U.S. which are now mostly small-run projects other than the New Yorker. I looked but can’t seem to find any statistics about publishing numbers for 文芸誌 (bungeishi, literary journals). The eye test does suggest that if these magazines aren’t thriving, they at least aren’t going extinct; you can find massive volumes (several hundreds of pages each) with serious writers at every bookstore in the country, and volumes like the 120th anniversary edition of 新潮 (Shinchō) that I mention in the episode seem to be selling out online. I’d recommend running to a physical store if you’re still looking for a copy. (And it’s kind of a shame that these magazines aren’t digitized.)

This reminds me of when I was studying abroad in Tokyo. One night I was walking home from Shinjuku to the apartment where I was temporarily staying near Waseda. I came upon a stack of magazines illuminated by a street light. The one on top was a copy of 文藝春秋 (Bungeishunjū), the copy with the Akutagawa Prize-winning stories from Wataya Risa and Kanehara Hitomi that I’d just read that semester.

I took it home with me and eventually brought it back to the U.S., but sadly I threw it out while moving at some point between New Orleans, Chicago, Yokohama, and Osaka. It’s kind of nice to know that I could always get a new copy for 400 yen on Mercari if I wanted to, which seems to be the going rate.

The latest copies of Shinchō seem to be going for around 2,500 yen or so. Probably netting just a few hundred yen minus fees and shipping. I’m not sure why the 転売ヤー (tenbaiyaa, resellers) would even bother at that point. I imagine that prices will probably settle down at some point, so if you make it to a physical bookstore and they aren’t there, just give it a little time, and I’m sure you’ll get one for a reasonable price.

There are likely other magazines with 随筆 (zuihitsu, miscellaneous writing/essays) available, but even if you have to go to the library to peep some of these, it’s probably worth it.

Sentence Diagramming

I just sent out the newsletter for April. This month I focused on diagramming Japanese sentences. This is something I’ve been trying to do recently to get a better sense of Japanese sentences with the goal of improving my writing. The basic idea is this: Can you break down a Japanese sentence into its most fundamental structure so that you can understand it more easily? And once you’ve done that, could you compose your own sentence by filling in the blanks? Or could you reverse this process as a way to proofread and revise sentences you’ve written to test their seaworthiness?

The simplest example of this is this:

AはBです。

And the second simplest (and perhaps the most frequently analyzed in linguistic circles) is this:

XはYがZです。

These are pretty easy to make sentences from:

夏は暑いです。

Summer is hot.

京都は観光客が多いです。

Kyoto has a lot of tourists.

But just because the structures are simple doesn’t mean that we need to make simple sentences! These examples have the same structure:

冷凍した肉が腐っているときのサインは、以下の通りです。

Here are some of the signs that your frozen meat is rotten.

カフェインは、飲食物の成分として作用が非常に強いです。

Caffeine as an ingredient in food and drink has incredibly strong effects.

The first I found in this article about freezing meat. The second I adapted from this article about the health benefits of caffeine. (I excised it off from a slightly more complicated sentence.)

Both of these articles I discovered thanks to the Edge browser, as I mentioned in the newsletter. I really can’t recommend using its localized news features enough.

I know this stuff isn’t great literature, but I do think it makes excellent study material. It’s low stakes, simple sentences, with vocabulary that’s useful in everyday life about topics that you are already familiar with. If you’re looking for somewhere to start, here’s another perfectly good place: 適量のコーヒー (tekiryō no kōhī). An additional article about the health benefits of caffeine.

So consider this month a call to action. Both to myself and to you. Can you read more Japanese articles, and can you be more mindful of the sentence structure as you’re reading?

Go give the newsletter a read for more details. And check out the podcast where I go over the strategy and talk about the Murakami translation publication dates, which I forgot to mention last month (in the pod: I did mention it in the newsletter).

お湯割り

In the newsletter this month I wrote about 角ハイ (kakuhai). This is a combination of 角瓶 (kakubin), Suntory’s flagship whiskey, and ハイボール (highball), a mixed drink made from liquor and usually some kind of carbonated beverage, often soda water. Go give it a read. 角ハイ has a pretty interesting story.

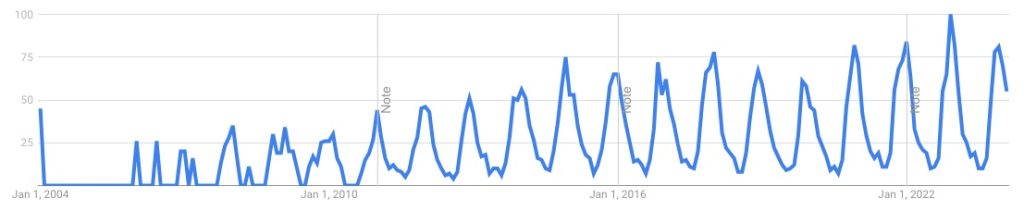

I talked about it over on the podcast as well, and one thing I mention there that I left out of the newsletter is the Google Trends information I found for お湯割り (oyuwari, cutting alcohol with hot water):

The general trend is a gradual increase from the mid-2000s, although several Japanese websites note that お湯割り started to become more popular in the 1970s, well before Google was tracking data. What’s more interesting to me, however, is the fact that searches for お湯割りvary by season! There’s some variance within the ハイボール uptrend that I used in the newsletter, but it’s nowhere near as clearly defined as お湯割り. You can see very distinct peaks and troughs which resemble the graphs you see for the number of flu cases over the course of the year.

I guess this makes sense. When the weather gets cold, people get interested in drinking お湯割り, and when people get interested in drinking お湯割り, they start Googling to figure out how to make one.

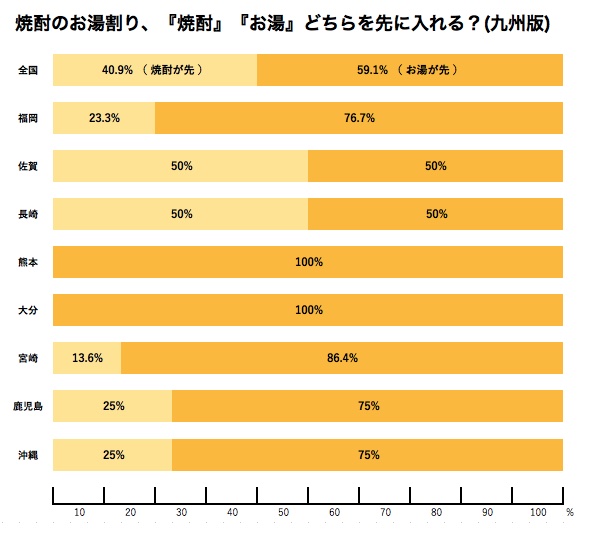

I’ve done the hard work for you and can point you to this website, which has this interesting set of data:

As you can see, most people in Kyushu pour the hot water in first. The site advises a temperature of 66 Celsius (150 Fahrenheit).

How to Japanese Podcast – Episode 48 – The 1,000-yen Haircut and まとめる

On the podcast this month, I continued the conversation about value in Japan, specifically looking at the 1,000-yen men’s haircut, which I think is one of the worst values in Japan, and the 2,000-yen men’s haircut, which is one of the better values in Japan.

These are cuts that are available at what I call “value barbers” and “extreme value barbers.” I don’t have a good sense of anything outside these two establishments, other than that anything beyond these two seem to go up in price dramatically quite quickly; there doesn’t seem to be much in that 2,000-5,000 yen range, although I did have the my worst (non-self afflicted) haircut in Japan at what I might call a “value luxury barber” for around 4,000-5,000 yen.

Let me know what you think and whether I’ve missed anything. I was able to give some good advice for getting a men’s haircut in Japan, but I’m especially clueless about the salon experience for women. I’d be curious to know what the customs are like there.

The one kind of “set custom” that I may have forgotten to mention on the podcast is the kind of 義理マッサージ (obligatory massage) that barbers give customers: After applying hair tonic at the very end of a cut, the barber then will rub your shoulders, clamp your hands together, and then give you a quick bump on each side (and maybe the top of the head?). I sometimes feel a little awkward enjoying this.

And over on the newsletter I wrote about the verb まとめる (matomeru, bring things together). I talked about this at the end of the podcast as well. Give it a listen!