This year has been a bit of a wash so far in terms of my own productivity. I caught COVID in early January, fell into a Murakami hole from February to May, and am now fully immersed in Hyrule. I can’t recommend Tears of the Kingdom (TotK) highly enough. I probably need to take a break from it (as of May 30, I’m about 50 hours in), but it is…unparalleled in terms of breadth.

If you haven’t played it yet and are trying to avoid spoilers (which I’d recommend if possible), it’s probably best not to read on. I won’t be saying much, but I’ll be saying something.

I’ve been consuming a ton of media about Tears of the Kingdom as well. Polygon’s article “Tears of the Kingdom is saving me from my checklist obsession” captures an aspect of the game that I also felt about Breath of the Wild, which I played and then set aside before eventually picking back up and finishing. I liked it enough to start a second game last fall (which was also derailed by Murakami). I think I enjoyed it even more the second time. I had the right state of mindfulness to enjoy the game for what it was whenever I happened to be playing it. I didn’t force it along the path. I tried to take it as it came. Whether that was doing a quick shrine puzzle at lunch, exploring a landscape and hunting down Koroks in an area I’d never been before, or advancing the story. BotW is mindfulness condensed into game form. (I also played it English. I’ve realized that I need to play games in English first to understand mechanics so that they don’t feel like study.)

TotK feels denser, and some have argued that it doesn’t have the same open, empty, almost lonely “vibes” as BotW. One of these is The Bad End podcast episode about TotK.

I’d agree with that statement for the most part. BotW feels much more, for lack of a better word, wild. The same sense of mindfulness is, I think, critical to enjoying TotK, but the game perhaps doesn’t distill it as purely as BotW.

That said, I do think TotK does have vibes. It’s just that all of the TotK vibes are stored in a single place: The Depths. This is what I hate to spoil for anyone (which is why I won’t post a screenshot). Essentially, Nintendo created an abstract almost blank wilderness in TotK and set it underneath Hyrule, totally confounding all expectations they created for the game; nearly every trailer and promo for the game heavily emphasized the sky islands, and in a true miracle, most everyone writing about and reporting on the game seems to have maintained an embargo for content about the Depths. While the sky islands do play an important part of the game and have their own unique atmosphere (I love the Philip Glass-inspired minimalist brass soundtrack), I think the Depths captures that sense of the unknown, the expansive, the surprising, and the dangerous that BotW offered us for the first time. It doesn’t hurt that the music for the Depths is hands down the best in the game.

I do think that the next Zelda game will have to reboot the series entirely: I don’t know if the center will hold for much longer. I’m sure there’s something that Nintendo could add to expand the game, maybe even to the degree that TotK expands BotW (?!), but I wonder whether that’s the best idea.

The Bad End podcast is one of the very few complex critical voices I’ve seen discuss TotK, and some aspects they are slightly down on are the story (I laughed out loud when they asked why Zelda hadn’t looked in the basement before) and the mechanics (I think asking whether missiles and homing devices and Minecraft dynamics belong in Zelda is a fair question, but the game is still great for these additions).

But I’m not sure I understand the “Permaweird” angle they take. The podcast uses Venkatesh Rao’s article “The Permaweird” to discuss Hyrule as an encapsulation of the (need for a?) permanent state of crisis in the world.

(The theory itself to me feels like an extremely complicated form of bothsidesism, to be honest. It feels like a true crisis when Republicans are actively disenfranchising minority voters, attempting to make it illegal to be part of the LTBTQ community, and continuing to support the gun lobby, so I can’t help feeling gaslit whenever someone tries to criticize the need for collective urgency. The Bad End is using the theory in a different sense, I think, although I’ll admit I may not fully understand their approach.)

I prefer to use “One Punch Man” as a metaphor for TotK. If you haven’t seen the anime, you should drop what you’re doing and watch it immediately (between sessions of TotK, of course), but basically it’s a send up of “Dragon Ball Z” and other famous anime combined with the satirization of trade associations. The central element it criticizes is the relentless need to find a larger threat, a more evil villain, a more pressing disaster, a more intense voice actor.

To a certain extent, the stakes in Zelda—as in superhero movies—will always be 0 or 100. The world will either end or it won’t. Evil will triumph or it won’t. Otherwise, what’s the point, really?

This is why superhero franchises reboot constantly. A reboot allows them to start fresh without needing to one up (One Punch, as it were) the stakes.

For now, however, TotK has miraculously managed to one up the stakes. Nintendo made a shrewd decision when they used Calamity Ganon as the BotW villain. Calamity Ganon is more abstract and cloud-like than Ganon has been in many Zelda entries. TotK seems to surpass this, ironically, by making Ganon more of a human threat.

Maybe there’s another angle they can take, something that would make me want to spend another 100+ hours in a Hyrule that looks and feels very similar to BotW and TotK, but I’m starting to get the sinking feeling that if they did, I might not be pulled back into the world in quite the same way.

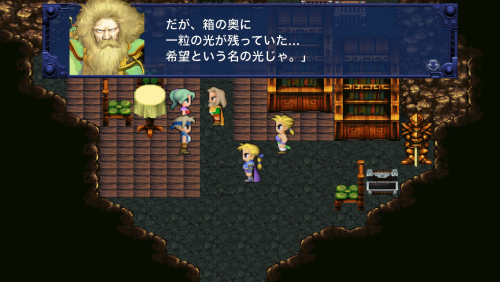

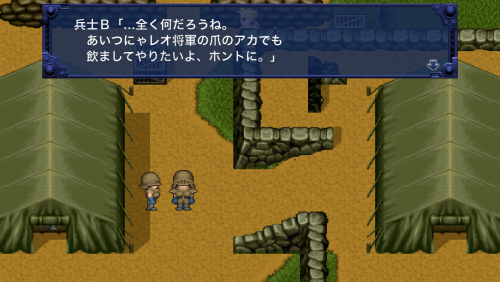

Apologies for the lack of Japanese content this month. I can say that TotK enables you to easily select the Japanese language voice track in the settings so that the cutscenes play almost like an anime. And don’t forget that playing the game in Japanese (and “cheating” in Japanese) is a perfectly good way to study.