1Q84 comes out next Friday! This will be the first major Murakami release when I’ve been in Japan. I was here when 『東京奇譚集』came out, but most of those stories had been published in magazines beforehand. Also, I had to drive 20 minutes to the closest bookstore to get my copy. This time I should be able to pick it up almost anywhere. I plan on making the rounds Thursday evening to see if anywhere accidentally puts it out early, but I don’t have much hope for that. I’m really tempted to take off from work on Friday. It will depend on what the workload looks like next week. If I take off from work, then the liveblog should begin at around 9AM JST on Friday. If not, probably 7PM. Check back next week on Wednesday or Thursday for an estimated start time.

Category Archives: Murakami

2 Weeks Until 1Q84 Liveblog!

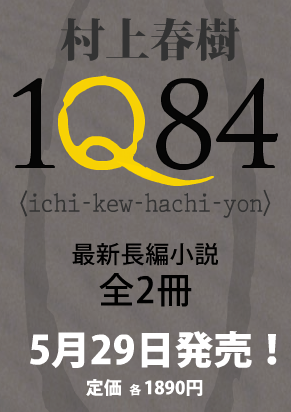

T-minus two weeks and counting until the release of Haruki Murakami’s new novel 1Q84! To commemorate the occasion, I’ll pick up a copy of the book on Friday the 29th and then liveblog it all weekend. For those of you who don’t read any Japanese, maybe this will give you a little taste of the reading experience. You’ll probably have to wait a couple years for the translation. I’ll try to keep the spoilers to a minimum: this will mostly be an exercise in extreme Murakami fanboy-ism.

号外 – One More 1Q84 Thought

I think Dimitry Kovalenin has a livejournal account? If so, that’s awesome. It looks like he might be doing the Russian translation of 1Q84? Also, a commenter on the entry found information in a database of proteins, or something, with the label 1Q84. Apparently the enzyme acetylcholinesterase is also related. This enzyme is active in synaptic transmission and is the target of certain nerve agents…namely sarin gas. Which would make me seriously re-think prediction 3 – maybe he’ll address the Aum attack rather than WWII. Hooray for Google Translations.

Yes, this is all super-otaku, but if you can’t find something in life worth getting crazy about, then you’re probably a really boring person.

Dimitry, if that’s you, I’m sorry about the kumozaru thing, heh.

Predictions for 1Q84 (Updated x2)

As mentioned previously, Shinchosha has announced that Haruki Murakami’s new book will be titled 1Q84 and that it is scheduled to be released in early summer. Here are some of my predictions for the book:

1. It’s going to be a monster. Murakami has admitted that it’s long, longer even than the dreaded Kafka on the Shore. Consider also that it’s been seven years since he wrote Kafka, and during that span he has produced only translations (The Great Gatsby, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Long Goodbye), short stories (Strange Tales from Tokyo, 『東京奇譚集』), a set of memoirs (What I Talk About When I Talk About Running), and a short-ish novel (Afterdark). He’s been busy, for sure, but he started writing in December 2006 (Rubin 338), which means he has probably spent close to two years writing the novel. In the second update to Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, Jay Rubin has speculated that this might be the “comprehensive novel” that Murakami has wanted to write for some time. No pressure.

2. He will not re-work one of his previous short stories or a section of a novel. Murakami has a long history of reworking old stories. Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World reworked a medium-length story titled 「街とその不確かな壁」. The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, Norwegian Wood, and Sputnik Sweetheart all reworked short stories, and with the exception of Sputnik Sweetheart, the reworked versions are stronger than the original and have been received better critically than works he wrote from scratch (Dance Dance Dance, South of the Border, West of the Sun, Kafka on the Shore). Murakami is at his best when he re-explores wells he’s already partially dug. That said, he’s become so popular with international audiences that he can no longer perform this magic without it being obvious. I continue to hope he looked back on his old works for inspiration, but I think 1Q84 will all be brand new. Although… if it is the big fat 総合 novel he says he’s wanted to write, then maybe it will revise an old work. I was torn on this prediction. If he does use an old story as a foundation, it wouldn’t surprise me if it came from after the quake.

3. World War II will be a theme. Murakami used the war as a central theme in Wind-up Bird, showing the brutality and meaninglessness of war through the skinning of a Japanese agent and the slaughter of zoo animals. He addressed Japanese unease with the Chinese in “A Slow Boat to China,” one of his first short stories, and his most recent novel Afterdark is almost allegorical for the difficulty of coming to terms with the war: a Japanese salaryman has pains in his fist and a bag of stolen clothes but seemingly no true recognition of the beating he handed out to a Chinese prostitute earlier in book, despite the fact that he remembers the event. This time, however, I predict Murakami will address Japanese brutality in the Pacific more directly. In a recent Japan Times article, he mentions Singapore during the war:

Murakami was frequently in court for the Aum trials and saw cultists who had merely obeyed guru Shoko Asahara’s order to release the sarin. Through this experience, he "seriously thought about" the war, he said. "During the war, no one could say ‘No’ to senior officers’ orders to kill prisoners of war. The Japanese did such things in the war. I think the Japanese have yet to undertake soul-searching."

As an example, Murakami mentioned an article contributed by former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew to a Japanese newspaper in which he related the cruelty of Japanese troops who occupied Singapore during the war. But once the war was over and they became POWs to the British, they became conscientious and worked very hard to clean up Singapore’s streets, Lee wrote.

Taking this into account along with his recent acceptance speech for the Jerusalem Prize and the title of the book, possibly a homonymic salute to George Orwell’s 1984, and Murakami seems poised to undertake some cultural soul-searching.

4. It’s going to be great. I personally thought that the 東京奇譚集 stories were a return to form. (Strangely enough, a return to his 1984 form – Murakami serialized the stories from 『回転木馬のデッドヒート』 in ’83 and ’84, and 奇譚集 is very similar in form and theme to those stories.) Afterdark was experimental, a “concept album” I believe someone said (or maybe that’s what Murakami said about after the quake), so it will be interesting to see where 1Q84 takes Murakami. He’s been busy with translation and his memoirs, and historically he’s kept the same pattern – work on the novel in the early morning, go for a run, translate in the afternoon – when writing some of his big works.

5. There will be a flush of short stories later this year. Murakami never rests as is clear from his running memoir. He’s always training himself for something. He might pace himself at times (translation and short works, he’s admitted, don’t take the same mental toll that novels do), but he is always working on something. Writing short stories happens to be the way he recovers from writing a novel, and if this is a massive novel, perhaps we can expect a bunch of short stories. Once everything for publication is set, I bet he’ll get back to writing short works, which will hopefully be published later this year. 2009 could be the year of Murakami.

Updated:

Found the link to the Houston Chronicle article where Murakami says his new book will be twice as long as Kafka on the Shore. They put it in the archives and switched the original link.

Also, realized most folks from the large amount of traffic might not be able to read 『回転木馬のデッドヒート』. That’s Japanese for Dead Heat on a Merry-go-round, an untranslated collection of Murakami stories I wrote an article about here.

Updated again:

Probably wrong about prediction 3.

号外 – 1Q84

Whoa. So Murakami’s new book has a title: 1Q84. Pronounced いちきゅうはちよん. Check out the link to see his updated Shinchosha page. What a strange title. At first glance it looks like 1984, and with his recent talk of eggs, perhaps this is Murakami versus the man. He’s said it will be longer than Kafka on the Shore, and in the updated version of his book Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, Rubin has speculated that it might be the "comprehensive novel" that Murakami has mentioned as his long-time goal. I heard it was coming out in May, but the site says 初夏 – early summer. Is that May?

Shinchosha is promoting it as his next big mysterious novel – they have links to Hard-boiled Wonderland, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, and Kafka on the Shore. Sadly, I think that’s the order I’d put them in from best to worst, and if 1Q84 has to follow Kafka, it could be crap. やれやれ。

号外 – Uncool Compound – 盗作

盗作 (とうさく) is a pretty straightforward compound; a literal reading provides “stolen-work”, and from there it’s easy to extrapolate to actual meaning – plagiarism.

Perhaps plagiarism is too harsh a charge, but however you measure it, the Japan Times seems to have poached research from a Néojaponisme article I worked on. Roger Pulvers uses Dimitry Kovelenin’s mistranslation of kumozaru in his Counterpoint column today. It’s awfully similar to the Néojaponisme piece, even down to the use of the monkey proverb:

Dmitry Kovalenin, the excellent Russian translator of the works of Haruki Murakami, once tripped over the translation of kumozaru, meaning the spider monkey that is native of Central and South America. Kovalenin assumed, it seems, that Murakami was referring to a mythical animal, so he used a bizarre made-up equivalent of "spider" and "monkey" in Russian. Another Japanese proverb tells us that "even monkeys fall from trees"; and Kovalenin was man enough to bring this particular fall to light himself by acknowledging it publicly.

The worst part is that Pulvers gets it wrong; as far as I know, as far as the transcript reads, Kovalenin did not in fact “man up.” He boasted about the clever translation and was then called out by other translators at the convention.

I guess there’s a chance that Pulvers came up with the research independently, but there are only three hits for "Dimitry Kovalenin" and "kumozaru" on the Internet (make that four) and judging from the rest of the article, he doesn’t seem that creative: the column is a mish-mash of anecdotes, held together by the general theme that “bad pronunciation can make you say funny/rude things”. He sprinkles this with two suggestions – face the speaker when interpreting and use common sense.

I wish the Japan Times would pay me to write stuff like that.

号外 – Whoa

"He just finished a novel, ‘twice as long as Kafka on the Shore,’ he says, which will be published in Japan in May."

From this interview.

号外 – Oops!

I’ve got another Murakami-related piece online over at Néojaponisme. Just a funny little extract from a Murakami conference. Dimitry Kovalenin clearly hasn’t been to a zoo for a while. Although, in all fairness, spider monkeys don’t live in Russia – too cold, no onsen.

It is unclear when Kovalenin did his translation of the story, but nowadays there are several things he could have done in terms of fundamental groundwork for the translation, none of which would have taken much time.

A search for くもざる (kumozaru in hiragana) turns up a variety of strange images, including the cover of the collection and a few monkey pictures, but Google also suggests that you might be looking for クモザル (“もしかして:クモザル”). Search for the katakana version and you’ll find nothing but real monkeys.

Google Images is quick and easy way to research what a word means and implies to people. And it’s good for more than just people, places and animals; a search for 派手, a word that can sometimes be difficult to translate in natural-sounding English, is revealing. An image search will never tell you what a word means, but it can provide you with some usage clues.

Wikipedia entries are all cross-linked with their foreign counterparts. A list of languages for a given entry is provided in the left sidebar. This makes it an excellent tool for translation research

Of course, this doesn’t always work. A Wikipedia search for くもざる currently brings up only three results – the Asahiyama Zoo, Murakami Haruki, and Anzai Mizumaru. Even クモザル is a little confusing; it is included within the Japanese entry for Atelidae, “one of the four families of New World monkeys.” But if you browse through that section, クモザル亜科 is listed as one of the species, and there are half a dozen examples of spider monkeys.

Professor Numano was quick on the draw with his Kōjien citation, so I’m guessing he looked it up in an electronic dictionary. Go ahead, get yours out now. I already checked mine, and it’s nearly identical to the definition that he gave in Japanese. (オマキザル科の哺乳類。数類があり、中米から南米北部の森林に生息。) SPACEALC, a useful online dictionary that often generates a horde of contextual examples, also gives spider monkey as the definition.

Wikipedia does not list Yoru no kumozaru as having been published in Russian, so perhaps Kovalenin translated it especially for the symposium and dodged a bullet by discovering his mistake quickly. As they say in Japan, even monkeys fall from trees. The translator’s burden is a heavy one – very little of the credit for success and all of the blame for failure. Modern resources and looking up every damn word you are unsure about can help ensure that you don’t win the Miss Translation pageant.

Still No Nobel

A day has gone by, and Murakami still hasn’t won the Nobel Prize. I’ve got a small piece about Murakami and the Nobel over at Néojaponisme.

He really came out of no where in 2006 to contend, at least in the bookmakers, for the Nobel. There was a strong push for him that spring, although push might be too strong, as someone has to be pushing. Supposedly the symposium I mention was to help increase his chances, but I think the other prizes he won were more important. That and the fact that he’s translated into a ridiculous number of languages.

I’m taking a Murakami vacation until his next book comes out. That vacation starts now.

号外 – 2009

Alas, Murakami was not selected for the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2008. It went to some French guy instead. The wait for 2009 begins now.