Just a quick post this month. I’m in the Japan Times with a piece inspired by a conversation I had with a colleague during a business trip in June: “Get in tune with the sound of Japanese vocabulary.”

I found some interesting links on sound symbolism in Japan. Most of the research seems to involve onomatopoeia and how sound is representative of the meaning. That’s not exactly what I had in mind when I was writing the piece, but it’s interesting nonetheless.

And as a random aside—although I guess it counts as listening practice—I went to the first Cinema Saturdays program at Wrightwood 659 yesterday where they showed the Japanese documentary 愛と法 (Of Love and Law).

Wrightwood 659 is a gallery in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood designed by Tadao Ando. The gallery is in an old brick building right next to the Eychaner house. I believe the Eychaner house was the first residence Ando designed in the United States, and Fred Eychaner founded Wrightwood 659.

The building was gutted, and they let Ando work his magic inside.

It’s been open since fall of 2018, and they’ve had a few nice exhibits so far, including an Ai Weiwei exhibit (before they actually opened as Wrightwood?) and one with a look at Ando and Corbusier’s buildings. Tickets are $20, but they release a lot of free tickets if you follow their email list. Definitely worth a visit, even if only to sit in the beautiful lobby space for a few minutes.

The Cinema Saturdays program was organized with Frameline San Francisco LGBTQ+ International Film Festival, the largest and longest running LGBTQ+ film festival in the world.

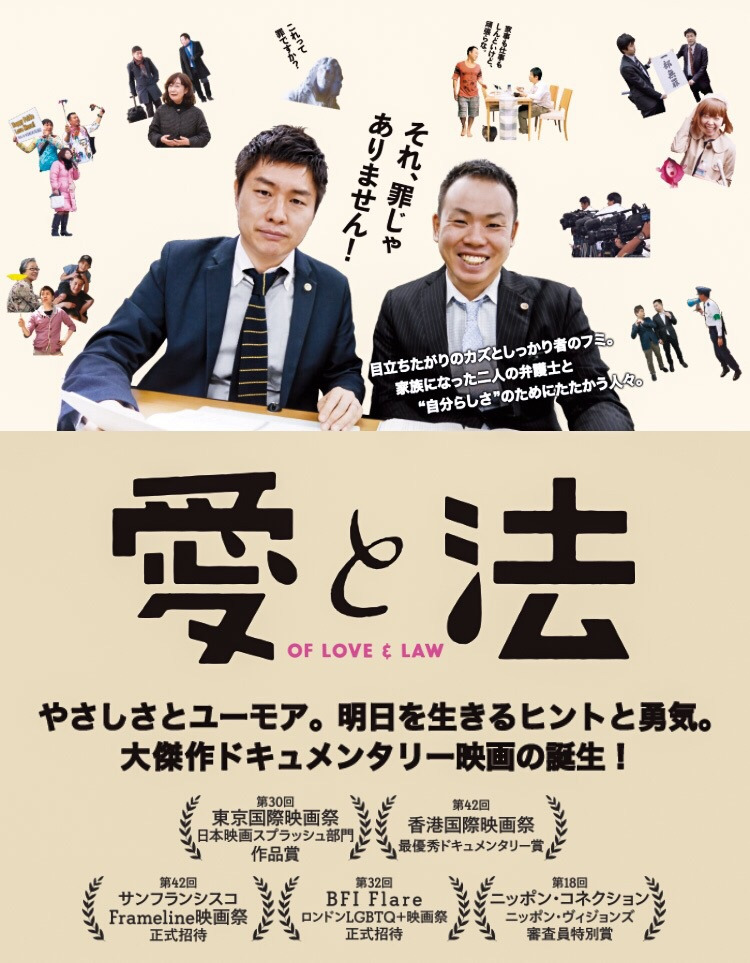

愛と法 (Of Love and Law) is a great documentary about the Nanmori Law Office run by Masafumi Yoshida and Kazuyuki Minami, a gay couple.

I really liked the way they rendered 愛 and 法 on the title screen, which is recreated on the website for the movie:

You have the literal “eye” within the “ai” of love, and the drop of water for the さんずい in law, which reflects the many tears in the film.

The movie itself was kind of incredible. The law firm has been involved in a number of headline cases including the teacher in Osaka who would not stand during the national anthem and Rokudenashiko and her artwork, so the film is able to intersperse their personal struggles from the mundane (the regular bickering of a married couple) to the more profound (debating with attendees at one of their workshops over whether gay people can ever be “family” in Japan) with the legal struggles of others seeking the freedom of expression in Japan. The overall impression leaves the viewer with a sense that the persecuted have a suffocating existence in Japan, but that there is hope and that hope needs to be defended.

Definitely worth seeking out! And Wrightwood 659 is worth a visit. Check the website for more information about the other Cinema Saturdays showings over the next three weeks.