I am guilty of gross Murakami-centrism. Despite the fact that I have read a moderate amount of Japanese literature in translation, in Japanese I have not ventured much beyond Murakami’s catalog other than a few short stories and a couple novels here and there.

I’ve known about my deficiency for some time now and have been actively trying to correct it. Whenever I have the chance to talk literature with a Japanese person, I ask them what their favorite book is. This has helped me accumulate a number of books to read, some of which I’ve actually started on.

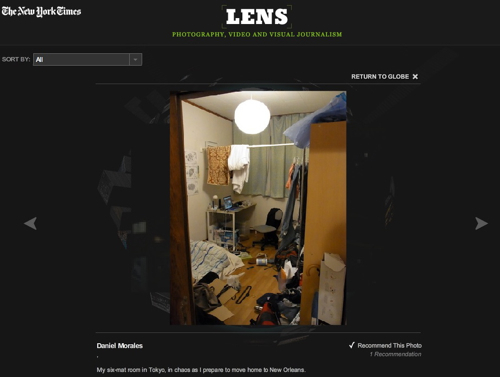

With my return to the U.S. imminent, I’ve packed up all the reading material I’ve accumulated over the past five years and (after trimming the selection a bit) sent everything home. I won’t be studying Japanese or Japanese literature at graduate school, but I’m still determined to continue my study of both on my own.

Because it will be difficult for me to get my hands on Japanese reading material, I put together a reading list with a little help from friends. In addition to the Japanese people I’ve had a chance to talk to, I asked some foreign friends to recommend material I was unlikely to have read. They did an amazing job. I asked the guys at Néojaponisme along with frequent contributor Sgt. Tanuki for recommendations from different eras – pre-Edo, Edo and post-Edo. I had a feeling that some of the crew at Mutantfrog Travelogue had read in areas outside my own specialty, so I asked them for general recs and was pleased with their suggestions. At the end I added a few of my own choices along with the books recommended by Japanese friends. So over the next 2-3 years, this will be the core of my reading list.

Do you have any suggestions? If you could only recommend one Japanese book (preferably something I haven’t read) what would it be?

Néojaponisme:

Matt Treyvaud (pre-Edo):

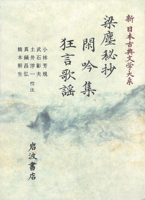

Since I was assigned “pre-Edo,” I’m probably technically obliged to stick to the holy trilogy of Kojiki, Man’yō shū, Genji. I would like to note that all three of these reward casual browsing, and you can enjoy them just fine that way, without dedicating your 30s to reading them all the way through in the original, but it seems kind of pointless to recommend books everyone already knows about. So I’m going to recommend a personal favorite among the lesser-known pre-Edo works: the Kangin shū 閑吟集.

Since I was assigned “pre-Edo,” I’m probably technically obliged to stick to the holy trilogy of Kojiki, Man’yō shū, Genji. I would like to note that all three of these reward casual browsing, and you can enjoy them just fine that way, without dedicating your 30s to reading them all the way through in the original, but it seems kind of pointless to recommend books everyone already knows about. So I’m going to recommend a personal favorite among the lesser-known pre-Edo works: the Kangin shū 閑吟集.

The Kangin shū is a loosely organized anthology of popular songs compiled in the 16th century by a flute-playing hermit (世捨て人). There are bawdy songs and pastoral songs, flip nihilism and sarcastic piety, all in a huge grab-bag of meters and language ranging from stately kanbun to rustic 5/7 lines ending in nō.

Close runner-up: Nifonno cotoba to historia uo narai xiran to fossuru fito no tameni xeva ni yavaraguetaru Feiqe no monogatari, a.k.a. the Jesuit edition of the Heike monogatari 平家物語. The content itself isn’t particularly special, but reading it in contemporary romanization is: it brings into the sphere of your personal experience many oft-overlooked facts about the history of Japanese and even Japan itself.

Sgt. Tanuki (Edo):

I’m going to cheat. If you’re really going to pick one thing from the Edo period to struggle through in Japanese, I think it really has to be Bashō 芭蕉’s Oku no hosomichi 奥の細道 (Narrow Road to Take Your Pick: A Far Province, The Interior, The Deep North, “Oku”). It’s been translated by everybody and her brother (hell, even I gave it a shot), but there’s just nothing like grappling with his prose and poetry in the original. If there’s anything that’ll prove the old saw that poetry is what’s lost in the translation, it’s this.

I’m going to cheat. If you’re really going to pick one thing from the Edo period to struggle through in Japanese, I think it really has to be Bashō 芭蕉’s Oku no hosomichi 奥の細道 (Narrow Road to Take Your Pick: A Far Province, The Interior, The Deep North, “Oku”). It’s been translated by everybody and her brother (hell, even I gave it a shot), but there’s just nothing like grappling with his prose and poetry in the original. If there’s anything that’ll prove the old saw that poetry is what’s lost in the translation, it’s this.

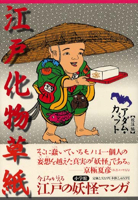

But you don’t need me to tell you about Bashō, so that’s not my pick. I’m going to recommend a book I haven’t even finished yet, but that I’m enjoying the bejeezus out of. That’s Edo bakemono sōshi (江戸化物草紙) by Adam Kabat (アダム・カバット) (from 小学館). This is a book of early 19th century kibyōshi, mostly by Jippensha Ikku (十返舎一九). Ikku’s the guy who wrote Shank’s Mare (a.k.a. Tōkaidōchū hizakurige (東海道中膝栗毛), also one of the books I’d take with me if I was exiled to Sado). Kibyōshi were a kind of comic book, adult-oriented (meaning sophisticated, not salacious, although they could be that, too), popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In the last few years there’s been a lot written about these in English – and this is going to seem pretty incestuous, because the leader in this movement was my grad-school advisor at A School Which Shall Not Be Named, somebody you probably know, too.

But the ones Kabat takes up haven’t been translated, and that’s a shame, because they’re just awesome. They’re part of the late-Edo fad for monsters, a fad that saw both the authentically shocking horror of Yotsuya kaidan (四谷怪談) and the kooky, funny monsters that populate these comix. Both of which feed straight into modern horror and humor manga. I mean, this is where my boy Mizuki Shigeru (水木しげる) got all his shit from.

Kabat’s editing is careful and helpful – he transliterates all the squigglies, and explains everything in modern Japanese, too – and of course part of the fun of the book is rooting for the gaijin who did all this work. But mainly the stories are cute, the illustrations are winning, and the whole package is just a priceless view into the comic imagination of the early 19th century. Very entertaining.

David Marx (post-Edo):

One book of interest is Sōkan no shakaishi (創刊の社会史) by Kōji Namba (難波功士) which looks at social trends through the publication of magazines. It’s a good intro to the history of Japanese youth and consumer culture, and shows why magazines are so important to both.

One book of interest is Sōkan no shakaishi (創刊の社会史) by Kōji Namba (難波功士) which looks at social trends through the publication of magazines. It’s a good intro to the history of Japanese youth and consumer culture, and shows why magazines are so important to both.

Mutantfroggers:

Roy:

I enjoyed the Onmyōji (陰陽師) novel series by Baku Yumemakura (夢枕獏), which is basically historical fantasy with a bit of a Sherlock Homes feel to it, based on the legends of the historical onmyōji Abe no Seimei. I’m sure you’re at least familiar with the film or manga versions, but I really liked the prose versions. Having lived in Kyoto for several years I’m actually very familiar with all the Heiankyo references and found it pretty easy to read, but as a Tokyo resident you may find that you need to read it with Wikipedia handy.

I enjoyed the Onmyōji (陰陽師) novel series by Baku Yumemakura (夢枕獏), which is basically historical fantasy with a bit of a Sherlock Homes feel to it, based on the legends of the historical onmyōji Abe no Seimei. I’m sure you’re at least familiar with the film or manga versions, but I really liked the prose versions. Having lived in Kyoto for several years I’m actually very familiar with all the Heiankyo references and found it pretty easy to read, but as a Tokyo resident you may find that you need to read it with Wikipedia handy.

Adamu:

1940-nen taisei (1940年体制) by Yukio Noguchi (野口幸雄) is a “pop economics” book about how the structure of many Japanese institutions we know today – regional newspapers, banks, labor practices, etc. – are largely a product of the wartime economy. A very interesting take from a former finance ministry bureaucrat.

1940-nen taisei (1940年体制) by Yukio Noguchi (野口幸雄) is a “pop economics” book about how the structure of many Japanese institutions we know today – regional newspapers, banks, labor practices, etc. – are largely a product of the wartime economy. A very interesting take from a former finance ministry bureaucrat.

My additions to the list:

Mahoro ekimae Tada benriken (まほろ駅前多田便利軒) is a novel written by Shion Mitsuura (三浦しおん) who I don’t know very much about. She regularly gets published and serialized in major magazines, but the photo on the cover was what first drew me to the book. The librarian at the junior high school in Nishiaizu always put her favorite books out on display, and this one caught my eye. Eventually I picked up a copy for cheap at Book OFF, but I still haven’t gotten around to reading it. It may be a little superficial to judge a book by it’s cover, but sometimes books that look good end up being a nice find. Speaking of which…

Mahoro ekimae Tada benriken (まほろ駅前多田便利軒) is a novel written by Shion Mitsuura (三浦しおん) who I don’t know very much about. She regularly gets published and serialized in major magazines, but the photo on the cover was what first drew me to the book. The librarian at the junior high school in Nishiaizu always put her favorite books out on display, and this one caught my eye. Eventually I picked up a copy for cheap at Book OFF, but I still haven’t gotten around to reading it. It may be a little superficial to judge a book by it’s cover, but sometimes books that look good end up being a nice find. Speaking of which…

I introduced Kōhī mō ippai (コーヒーもう一杯) by Naoto Yamakawa (山川直人) last year, but I still haven’t found the time to read Volume 5 (the final volume) yet, so I included it in one of the boxes I sent back. I love the visual texture of Yamakawa’s drawings; they match perfectly with the tone of the stories, which is always very mellow and nostalgic. Reading this manga is like slowly immersing yourself in a 45C bath. Not any old bath, but an old-school aluminum tub on the second floor of a wooden building that rattles whenever a train goes by. And when you get out of the bath, you have a cold jar of coffee-flavored milk to cool yourself down. I found this manga randomly at Tsutaya before boarding a flight from Fukushima to Osaka. I was looking for SOIL, another serial published by Beam Comics, but they didn’t have the latest volume, so I picked this one instead.

I introduced Kōhī mō ippai (コーヒーもう一杯) by Naoto Yamakawa (山川直人) last year, but I still haven’t found the time to read Volume 5 (the final volume) yet, so I included it in one of the boxes I sent back. I love the visual texture of Yamakawa’s drawings; they match perfectly with the tone of the stories, which is always very mellow and nostalgic. Reading this manga is like slowly immersing yourself in a 45C bath. Not any old bath, but an old-school aluminum tub on the second floor of a wooden building that rattles whenever a train goes by. And when you get out of the bath, you have a cold jar of coffee-flavored milk to cool yourself down. I found this manga randomly at Tsutaya before boarding a flight from Fukushima to Osaka. I was looking for SOIL, another serial published by Beam Comics, but they didn’t have the latest volume, so I picked this one instead.

Tōkaidō chintara tabi (東海道ちんたら旅) is a random book that I came across when walking home from Oimachi one rainy evening. I was walking by the Nikon factory and happened to turn my head to the left just as I passed the book. It was absolutely soaked, but I rescued it and let it dry out. It’s still in readable condition and looks like a set of travel stories written by Shōichi Ozawa (小沢昭一) and Shintarō Miyakoshi (宮腰太郎).

Tōkaidō chintara tabi (東海道ちんたら旅) is a random book that I came across when walking home from Oimachi one rainy evening. I was walking by the Nikon factory and happened to turn my head to the left just as I passed the book. It was absolutely soaked, but I rescued it and let it dry out. It’s still in readable condition and looks like a set of travel stories written by Shōichi Ozawa (小沢昭一) and Shintarō Miyakoshi (宮腰太郎).

And finally for recommendations from Japanese friends. I haven’t read most of these, so the stories of how I met these people are probably more interesting than a summary of the books themselves. If you know anything about these books, let me know what you think.

I made friends with a Japanese guy who works at a translation company in Tokyo. When we met at a beer bar, he was amazed that I was interested in Thelonious Monk. He’s a good bit older than me, but between Monk, other music and literature, we had enough in common to become pretty good friends. He loves Jazz and the Beat poets, so much so that he ran off to India at some point in his 20s, inspired by Alan Ginsberg. When I asked about his favorite Japanese author, he quickly recommended Shichirō Fukuzawa (深沢七郎). “He writes amazing sentences,” he said. He recommended Narayama bushikō (楢山節孝), for which Fukazawa won the first Chūōkōron Prize in 1956. So far I’ve read the first two stories, including the title story, but I need to go back and read it more closely and finish the other stories in the collection.

I made friends with a Japanese guy who works at a translation company in Tokyo. When we met at a beer bar, he was amazed that I was interested in Thelonious Monk. He’s a good bit older than me, but between Monk, other music and literature, we had enough in common to become pretty good friends. He loves Jazz and the Beat poets, so much so that he ran off to India at some point in his 20s, inspired by Alan Ginsberg. When I asked about his favorite Japanese author, he quickly recommended Shichirō Fukuzawa (深沢七郎). “He writes amazing sentences,” he said. He recommended Narayama bushikō (楢山節孝), for which Fukazawa won the first Chūōkōron Prize in 1956. So far I’ve read the first two stories, including the title story, but I need to go back and read it more closely and finish the other stories in the collection.

Fukazawa is also famous for Furyū mutan (風流夢譚), which you can read more about over at Tokyo Damage Report. The work satires a radical takeover. During the takeover, the royal family is beheaded in front of a crowd. The story outraged conservatives, and one even attacked (UPDATE) the editor of Chūōkōron at his house (UPDATE), killing a maid and injuring his wife. Fukazawa was forced into hiding. Tokyo Damage Report has a translation of the story and a link to the Japanese original.

Two years ago I went with my roommate to his house for New Year’s dinner. It was the 2nd of January, not exactly New Year’s Day, but the food wasn’t exactly おせち料理: His dad is from Fukui, so they always serve up giant crabs as the appetizers. One of the guests was a slightly hefty Japanese guy with long, unkempt gray hair. He seemed to make a living mostly by tutoring high school and junior high school students, but he admired Albert Einstein (even taking fashion tips from him; hence, the hair) and fancied himself an academic in general. I went again this year with my brothers, and he not only questioned each of them about their respective fields of interest (biology, sculpture) but also managed to carry on decent conversations about both topics. His recommendation was Ao-oni no fundoshi o arau onna (青鬼の褌を洗う女) by Ango Sakaguchi (坂口安吾). A couple days later, extremely hungover after nomi-hoe-down action in Shimokitazawa, I walked an hour and a half from my apartment to Tonki Tonkatsu in Meguro to have 初カツ – the first tonkatsu of the New Year. Along the way I passed the Book OFF in Gotanda. I looked for Sakaguchi but could only find the collection of short stories Hakuchi (白痴). I was so out of it that I didn’t realize 青鬼の褌を洗う女 was included in the collection. The title (“The Woman who Washes the Blue Oni’s Loincloth”) makes the story sound intriguing, so I’m looking forward to reading this. No spoilers!

Two years ago I went with my roommate to his house for New Year’s dinner. It was the 2nd of January, not exactly New Year’s Day, but the food wasn’t exactly おせち料理: His dad is from Fukui, so they always serve up giant crabs as the appetizers. One of the guests was a slightly hefty Japanese guy with long, unkempt gray hair. He seemed to make a living mostly by tutoring high school and junior high school students, but he admired Albert Einstein (even taking fashion tips from him; hence, the hair) and fancied himself an academic in general. I went again this year with my brothers, and he not only questioned each of them about their respective fields of interest (biology, sculpture) but also managed to carry on decent conversations about both topics. His recommendation was Ao-oni no fundoshi o arau onna (青鬼の褌を洗う女) by Ango Sakaguchi (坂口安吾). A couple days later, extremely hungover after nomi-hoe-down action in Shimokitazawa, I walked an hour and a half from my apartment to Tonki Tonkatsu in Meguro to have 初カツ – the first tonkatsu of the New Year. Along the way I passed the Book OFF in Gotanda. I looked for Sakaguchi but could only find the collection of short stories Hakuchi (白痴). I was so out of it that I didn’t realize 青鬼の褌を洗う女 was included in the collection. The title (“The Woman who Washes the Blue Oni’s Loincloth”) makes the story sound intriguing, so I’m looking forward to reading this. No spoilers!

When I worked as a project manager for a translation company, I only got to go to one real enkai with clients. The only reason I was invited was that the client was supposed to be bringing its English native staff member – thus, the proliferation of foreigners. Sadly, the guy had too much work and wasn’t able to make it. That left me, the Japanese coordinator and the Syatch (which is what we call the 社長) meeting with the Japanese head of translation (who drank like seven beers and then went back to work) and a higher-up producer, I think, who had studied in Wisconsin and even been engaged to an American woman. For some reason it didn’t work out. His English was great, as you can expect, and he had even been to New Orleans during his stay in the U.S. (As we were leaving he asked me about the “titty bars” – that’s how good his English was.) He asked me about my interest in Japan, and as always I mentioned Murakami as the main reason I started studying the language. When I had the chance, I asked him who his favorite author was. He answered Seichō Matsumoto (松本清張). I can’t remember what novel he recommended or why, but on the way to New Year’s dinner this past January, I found Hansei no ki (半生の記) at the station bookstore while I was waiting for my roommate. I picked it because it was the shortest of his books and also because it’s a collection of stories. I think it’s nonfiction, or at least 私小説, which blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction.

When I worked as a project manager for a translation company, I only got to go to one real enkai with clients. The only reason I was invited was that the client was supposed to be bringing its English native staff member – thus, the proliferation of foreigners. Sadly, the guy had too much work and wasn’t able to make it. That left me, the Japanese coordinator and the Syatch (which is what we call the 社長) meeting with the Japanese head of translation (who drank like seven beers and then went back to work) and a higher-up producer, I think, who had studied in Wisconsin and even been engaged to an American woman. For some reason it didn’t work out. His English was great, as you can expect, and he had even been to New Orleans during his stay in the U.S. (As we were leaving he asked me about the “titty bars” – that’s how good his English was.) He asked me about my interest in Japan, and as always I mentioned Murakami as the main reason I started studying the language. When I had the chance, I asked him who his favorite author was. He answered Seichō Matsumoto (松本清張). I can’t remember what novel he recommended or why, but on the way to New Year’s dinner this past January, I found Hansei no ki (半生の記) at the station bookstore while I was waiting for my roommate. I picked it because it was the shortest of his books and also because it’s a collection of stories. I think it’s nonfiction, or at least 私小説, which blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction.