Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year Eleven: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year Twelve: Distant Drums

Murakami begins the memoir in Rome, and it quickly becomes apparent that his excuse from the prologue was cover for one of the very real reasons he decided to travel—the trip was an escape from some of the responsibilities of a young, popular writer in the Japanese literary establishment. After five years of writing and three of being a full time writer, Murakami is exhausted and wants an escape of sorts.

He personifies this exhaustion in the form of two bees buzzing in his head, going as far as naming them Giorgio and Carlo.

So he and his wife pack up, ask friends to take care of their cats, rent out their place, and take off for Rome.

He makes it clear that the memoir is made up of nonfiction he wrote for magazines while he was traveling, that the collection was basically serialized to a certain extent, and this introduction feels like he is pumping himself up to get ready to write. To write not only the rest of this memoir but the other fiction he would put together over the subsequent years.

There are some interesting Easter eggs in this part. Take a look:

The biggest problem was that I was tired. How the hell had I even gotten so tired? But no matter how it’d happened, I was tired. At least too tired to write fiction. That was the biggest problem I was facing.

I wanted to write two novels before turning 40. No, “wanted” wasn’t quite the word; I had to write them. That was very clear. But I was unable to get started on them. I knew basically what to write and how to write it. But I couldn’t get it out of me, unfortunately. It even felt like I might never write again. And the bees were buzzing around in my head. They were so loud I couldn’t even think straight.

The phone was still ringing in my head. That was also part of the sound the bees made. The phone. The phone was ringing. Ring ring ring ring ring ring. They were demanding things of me. Do an ad for a word processor or something, they said. Give a lecture at some women’s college, they said. Make some food you like for a feature photo shoot, they said. Do a magazine talk with some writer you’ve never heard of, they said. Give us your comments on sexism or overtourism or some musician who died or the revival of the miniskirt or how to quit smoking, they said. Judge some competition, they said. Write a 30-page “city fiction” story by the 20th of next month, they said. (And what the hell is “city fiction”?)

It’s not like I was particularly angry about any of it. Of course I wasn’t angry. Because these were all matters that had already been determined. Because I was simply being included. It wasn’t anyone’s fault, and no one had messed up. I knew that. In a certain sense, I was even an accomplice in the circumstances. It’s a winding bottleneck you have to go through to get to what I mean, but I still had a hand in it. So I had no right to get angry at anything. At least I don’t think I did. I was the one calling myself. In a certain sense.

That duplicity frustrated me. And left me feeling powerless. (35-36)

いちばんの問題は僕が疲れすぎているということだった。まったくどうしてこんなに疲れちゃったんだろうな?でもとにかく僕は疲れている。少なくとも、小説を書くには疲れすぎている。それが僕の抱えたいちばんの問題だった。

僕は40になる前に二冊の小説を書きたいと思っている。いや、思っているというよりは、書く必要があるのだ。それはとてもはっきりしている。でも僕はそれに手をつけることができないでいる。何を書けばいいのか、どう書けばいいのか、それもだいたいわかっている。でも書き出すことができないのだ、不幸なことに。このままでは永遠に書けないんじゃないかという気さえする。そして頭の中をぶんぶんと蜂が飛び回っている。すごくうるさくて、僕はものを考えることさえできないのだ。

僕の頭の中では、まだ電話のベルが鳴り響いている。それも蜂のたてる物音の一部なのだ。電話だ。電話がなっている。りんりんりんりんりんりん。彼らは僕にいろんなことを要求する。ワープロだかなんだかの広告に出ろと言う。何処かの女子大で講演をしろと言う。雑誌のグラビアのために自慢料理を作れと言う。誰それという相手と対談をしろと言う。性差別やら、観光汚染やら、死んだ音楽家やら、ミニスカートの復活やら、煙草のやめ方やらについてコメントをくれと言う。なんとかのコンクールの審査員になれと言う。来月の二十日までに「都会小説」を三十枚書いてくれと言う(ところで「都会小説」って一体なんだ?)。

僕は別に腹を立てているわけではない。もちろん腹なんか立てていない。何故ならこれらは既に決定された事項であるからだ。僕はただ単にそこに含まれているだけなのだから。誰が悪いわけでもなく、誰が間違っているわけでもない。それはわかっている。僕だってある意味では、そういう状況に加担している人間のひとりなのだ。かなりまわりくどい意味の隘路を辿って行くことになるけれど、それでもやはり僕だってちゃんとそれに加担しているのだ。だから僕にはそういう物事に対して腹を立てる権利なんてないのだ。たぶん、ないと思う。僕に電話をかけているのは、僕自身でもあるのだ。ある意味では。

そいう二重性が僕を苛立たせる。そして無力感を抱かせる。(35-36)

I love this section. You have a different perspective on the telephone. It comes up so frequently in Murakami’s fiction, which I wrote about it in my review of The Colorless Tazaki Tsukuru, but here it’s kind of a bother whereas in his fiction it generally connects, although can sometimes be ominous.

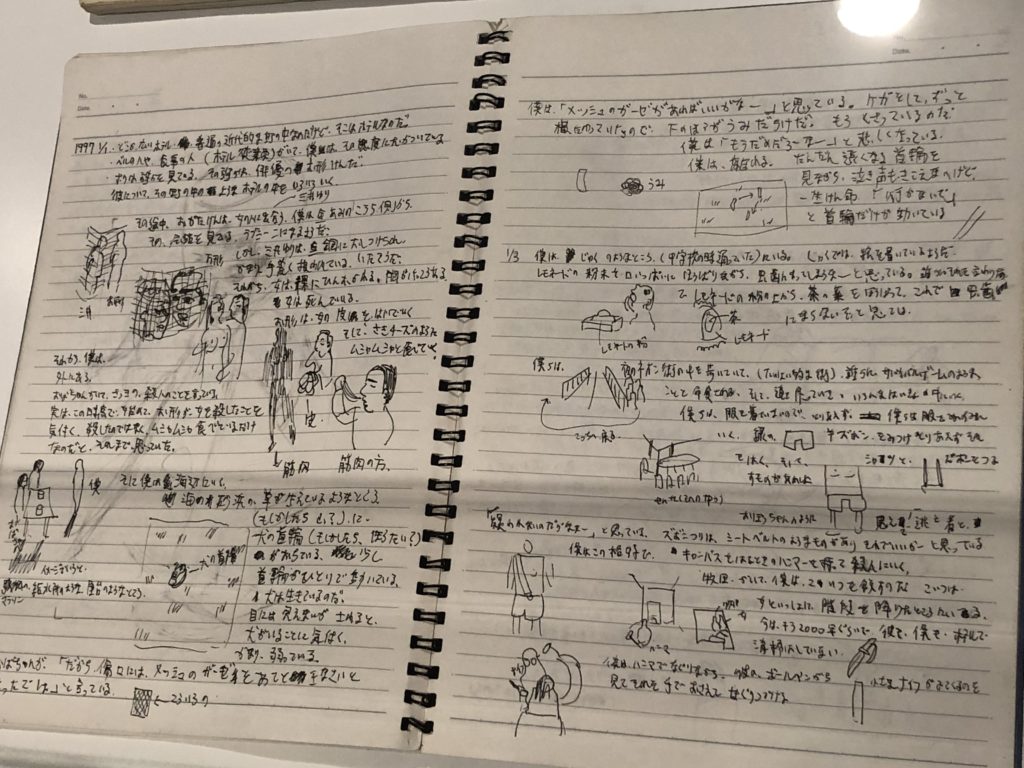

You also get some really interesting hints about the kind of projects he’s working on. He makes a clear reference to the short stories that would become 回転木馬のデッドヒート(Dead Heat on a Merry-go-round), which I wrote about (also over at Neojaponisme). The series was initially titled 街の眺め (Views of the City), and he seems to have figured them out in an effective way despite his skepticism here. He’s even said that the series was critical training for more realistic writing and that without it he wouldn’t have been able to write Norwegian Wood. The series ran from 1983-1985, so it spans the first part of his trip. (Edit: It actually does not, since his trip was from 1986-1989.)

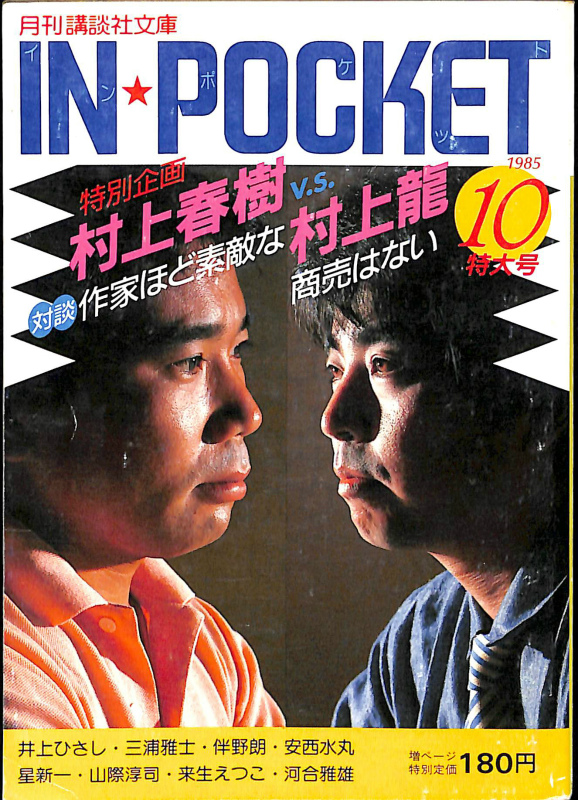

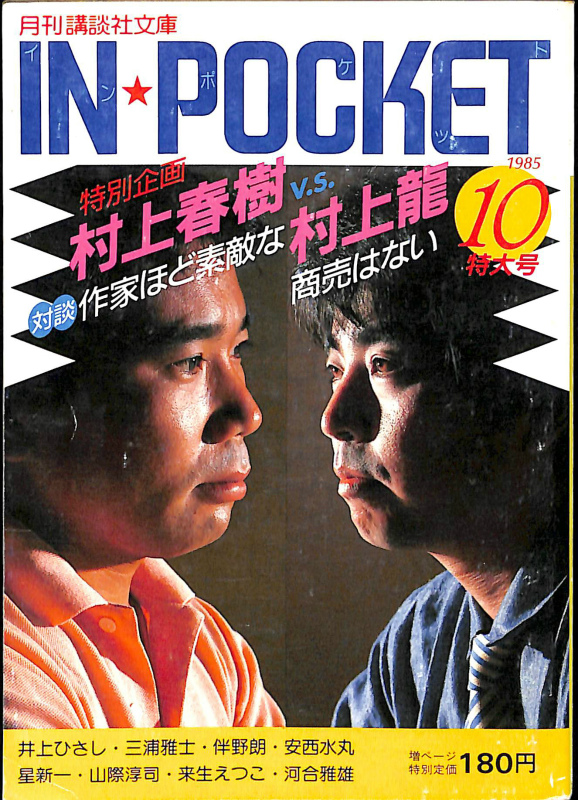

It’s also interesting that Murakami brings up 対談 (taidan) which I’ve translated as “magazine talk.” There’s nothing that really equates with the 対談 phenomenon in the U.S….except maybe podcasts? They are conversations between two people, often writers or intellectuals, and the transcript is edited and then printed in the magazine with photos of the writers looking very serious and intellectual. Murakami did one with Murakami Ryu that was republished in a hardcover format.

He also did at least 17 others between 1980 and 1984, which is about one every 2-3 months. I can’t tell whether that’s a lot or a reasonable amount, but combined with all the other asks on him and the essays and fiction he was also being asked, it was probably somewhat of a burden. I can’t imagine that these are as easy as showing up and having a chat with someone.

I wonder if he had a particular writer in mind with that line or if it was just kind of a random throwaway line.

If you’re interested in finding out, I’ve picked out all the 対談 Murakami did. This comes from Osakabe Yoshio’s now-defunct website that tracked all of his publications. It’s cached on Archive.org if you want to track it down. Here are the 対談 with English dates added:

May 1980:

happy end 通信 1980年5月号 Vol.2 No.4

対談: 映画月評 「出逢いを見て考えたこと」 (対談相手: 高橋千尋) 表紙と裏表紙

December 1980:

小説現代 1980年12月

対談: [特別企画-小説・ジャズ・野球] 「一九八〇年の透明感覚-村上龍Vs.村上春樹」

November 1981:

平凡パンチ 1981年11月2日号 第18巻第42号

原作者対談:映画ってなんだ!?」 『遠雷』立松和平Vs『風の歌を聴け』村上春樹 P27-29

December 1981:

対談: Hot Dog Press 1981年12月10日 第3巻第19号 No.37 P16-18

対談: HUMAN HOT INTERVIEW SPECIAL 「風の歌を聴け」 原作者 村上春樹 VS. 監督 大森一樹

April 1982:

朝日ジャーナル 1982年4月2日号 24巻 P26-32

対談: 「大衆化した「大学」はどこへ行く–「300万人の大学」執筆者 (漂う「大学」の脱出路)」 天野郁夫; 樋口恵子; 村上春樹

April 1982:

GORO 1982年4月22日号 第9巻第9号

カルチャー・ショック対談: 村上春樹VS糸井重里 湯村輝彦・イラスト P160-163

July 1982:

ユリイカ 1982年7月号 14巻 P110-135

対談: 特集 チャンドラー 川本三郎との対談 「R.チャンドラー あるいは都市小説について」

February 1983:

小説現代 1983年2月号 P222-233

対談: (五木寛之) 「言の世界と葉の世界」

May 1983:

クロワッサン 1983年5月10日 P48-51

対談: (道下匡子) 「あるとき、いちばん嫌いな人(ヤツ)を好きになってしまった!」

May 1983:

平凡パンチ 1983年5月30日号 第20巻第20号 P32-33

WIDE SPECIALならためて YMO でございます。 「創作作法対談 村上春樹氏とー坂本龍一」

July 1983:

「話せばわかるか」 (糸井重里対談集)1983年7月30日

対談: (糸井重里) 「1982.2.22 村上春樹と六本木・瀬里奈で話した」 エッセイ集

February 1984:

イラストレーション 1984年2月号 No.26 P34-40

対談: 特集:安西水丸・透きとおる影 対談:村上春樹vs水丸

February 1984:

GORO 1984年2月23日

対談: (安西水丸) 「男にとって”早い結婚”はソンかトクか」

February 1984:

ビックリハウス 1984年2月号 第10巻第2号 (通巻109号) P98-102

対談: (安西水丸) 「千倉における朝食のあり方」 安西水丸氏に聞く?T 小竹文枝・イラスト

March 1984:

ビックリハウス 1984年3月号

連載エッセイ: 人はなぜ千葉県に住むのか??D 対談: (安西水丸) 「千倉における夕食のあり方」

May 1984:

朝日ジャーナル 1984年5月25日 26巻 P43-47

対談: (筑紫哲也) 「若者たちの神々」 P81-82

Sometime in Fall/Summer 1984 (or February 1982?):

文庫版「話せばわかるか」(糸井重里対談集)

対談: (糸井重里) 「1982.2.22 村上春樹と六本木・瀬里奈で話した」

March 1985:

国文学 1985年3月号 30巻 P6-30

対談: (中上健次) 「仕事の現場から」(都市と反都市<特集>)

October 1985:

NEXT 1985年10月

対談: (島森路子) 村上春樹の世界 話題作「世界の終わりとハードボイルド・ワンダーランド」を手がかりに

October 1985:

IN★POCKET 1985年10月号 第3巻第10号 P4-74

対談: (村上龍、司会: 島森路子) 「作家ほど素敵な商売はない」 宮内忠敏/野上透/塚越亘/景山正夫・写真

February 1986 (and maybe February 1994):

「風の対話」 1986年2月

文庫版「風の対話」は 1994年2月4日 河出書房新社 (河出文庫)

対談: 五木寛之対談集 「ワンダーランドに光る風」

June 1986:

「on the border」 最新エッセイ+対談 1982-1985/オン・ザ・ボーダー 中上健次・著 1986年6月

対談: (中上健次) 「仕事の現場から」 P88-136

June 1986:

波 1986年6月 P6-11

対談: (中野圭二/村上春樹) 「アーヴィングが世界を見れば」

December 1989:

シネマ・ストリート パート2 (安西水丸著) 1989年12月12日

対談: (安西水丸) 「私の嫌いなもの・恐いもの」 285-299