After an overnight bus to Morioka and then another 2.5 hour ride from Morioka through the mountains to Ofunato on the coast, I arrived at the All Hands Volunteers base near the Sakari area of town yesterday at around 11am. I was oriented along with one other volunteer who was also on my bus.

All Hands has set up a command center in the Welfare Building in town. What I’ve seen of the main building is a small, generic Japanese office building. A room on the first floor has been cleared out and spread with temporary tatami mats. It’s being used as the main office and a common area. There is a big board with a list of teams and tasks, a corner where the All Hands staff works busily, wireless Internet that seems slow but more or less reliable, several Japanese kerosene heaters, and a shelf of luggage for the people who are living on the second floor. I haven’t seen the second floor yet, but I imagine it’s a big open area, converted office spaces, with mattresses and sleeping bags laid out.

One of the staff members drove me up to the other living area, Fukushi no Sato Center, which is about a 10-15 minute drive back up toward the mountains from base. I’m not sure how the numbers are split, but there are around 60 volunteers right now. The center is a rehabilitation center/old folks home which is currently housing some evacuees as well. It has a medium-sized Japanese-style bath on the first floor across from what looks like a dining hall. The second floor has a common room and several empty rooms where volunteers and evacuees are sleeping.

After a full day of travel, all I could manage was a quick walk down to the stores before a bath and bed. The walk was made quicker by a local lady who offered to give me a ride when I looked confused. She was an English teacher, eager to talk, and very friendly. Everyone here has been incredibly thankful for the help.

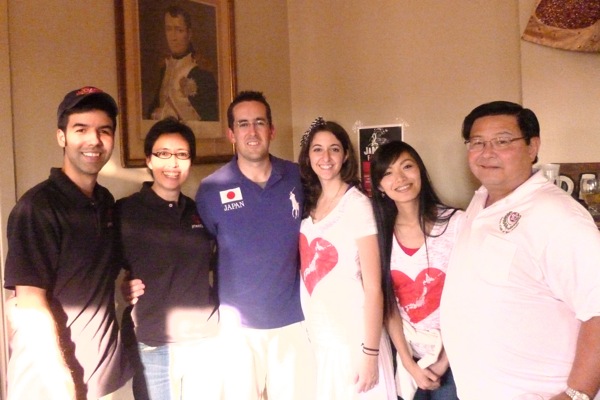

I passed out early and was up equally early. We left the Fukushi no Sato Center at 7:30 and had breakfast at the Sakari Base where we ate pancakes and had a meeting. I introduced myself along with the other new recruits and folks returning from breaks. I found out that one of the All Hands staff members is an alum from my high school. He graduated in’87, me in ’00. It’s a small, strange world. They also explained all the jobs and after we signed up.

I signed up with for a project titled “Ditch Bitches.” We were ten people and split into two groups, one of which was cleaning a larger canal with running water, the other of which was cleaning the roadside ditches in one of the neighborhoods hit by the tsunami. In the countryside, roads within towns and villages are all lined with knee-deep concrete drainage ditches. They are affectionately called “gaijin traps” because they are uncovered and foreigners have a tendency to drive into them and get stuck. In a bigger city like Ofunato, they are covered with heavy concrete slabs or grated metal drain covers. We pried all of these open and spent the day digging the mud and debris that accumulated in them. We dug up all sorts of things – broken tile and glass mostly, but also spoons, forks, iPods, broken CDs, little unopened bottled and can drinks, knicknacks, all of it covered in mud. At one point in a particularly deep, muddy section, we unearthed a mysterious frozen white liquid that was wrapped in some kind of packaging. It was still frozen after all this time.

We worked from 8:30 to noon, had an hour for a very satisfying bento lunch, and then worked until 4:30. The weather was nice – sunny and breezy, although the breeze did blow in a strong smell of rotten fish (or rotten something) that kind of lingers over the area of Ofunato near the coast, despite the fact that we were not in the immediate harbor area.

The area we were was still somewhat intact. There were a good number of buildings that are standing, and these increase dramatically as you move away from the coast toward higher ground tucked into the area between mountains.

Some houses had the first and second floors boarded up, some just the first floors, but many of the buildings had upper floors that haven’t needed to be gutted. But there are also empty lots where buildings have been completely swept away. In the distance I could see the NTT building closer to the coast that where we were, and it was large enough to still be there, but its windows too were boarded on the lower floors. On all the empty lots there are neat piles of collected metal, including some cars and appliances. We were dumping all our mud and debris on one of these empty lots using wheelbarrows. As I was wheeling one load to the dump site, I saw a plaque in the road that was marking the spot where the tsunami from the 1960 earthquake in Chili reached; needless to say, the recent tsunami went far beyond that spot.

My whole body is sore, and when I finish I will have forearms like Popeye. For now, I am glad to have Ibuprofen and glad to have been helpful.

After work, we bused back to the Sakari Base, had dinner, and did the evening meeting where team leaders reported back about the day and we all signed up for jobs tomorrow. I was tempted to sign up for something new to see a different part of the city and a different project, but I’m sort of a completionist and we didn’t quite finish all the ditches that we started today. I just hope that I don’t have to man up and jump in the canal tomorrow because I would come home very dirty. I’ll be wearing my work pants tomorrow, so it won’t be too much of an issue if I have to.

So now there’s just enough time to hop in the tub and then pass out in my sleeping bag before tomorrow. I’ve been outed as a snorer, which I don’t think bodes well for my restfulness tonight – rookies probably get a one day stay of leave on being disturbed for their snoring.