When I read Books 1 and 2 of 1Q84, I stormed through them, reading an average of 55 pages a day. I then promptly fell ill and did not venture far beyond the edges of my futon for the next week. (Belated apologies to some of the commenters who commented on that first post – I stopped responding once I got sick.) When I went to write my review of the book, I had a hard time remembering what had happened and an even more difficult time locating passages I wanted to quote. Doh.

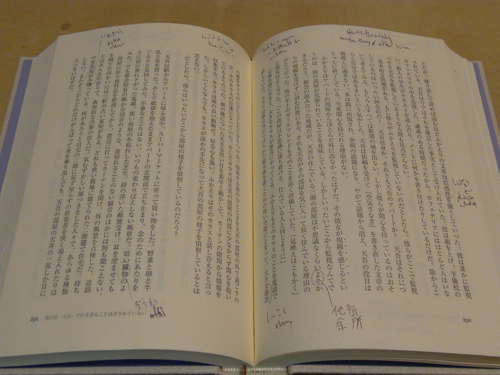

For Book 3, I’m reading at a much more leisurely pace. I’m only on page 348 but have been reading for nearly three weeks, which comes to 16 pages a day. One reason I’ve been reading more slowly is that I’ve been writing more notes. Take a look:

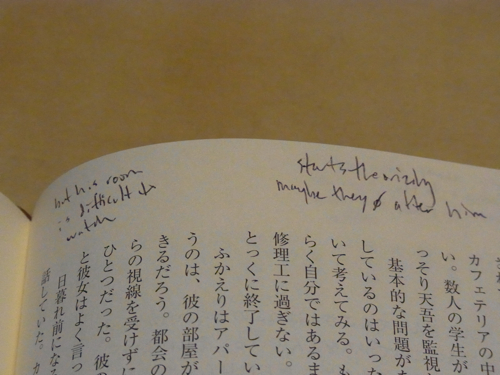

I’m using a technique a graduate student recommended to me when I was writing my senior thesis. At the time I was complaining that it felt like Japanese was going in through my eyes and straight out the back of my head – I didn’t feel like I was retaining anything. He suggested writing little notes above paragraphs to summarize the content. They don’t have to be extensive or detailed, but even a little summary of what is happening can help you 1) make sure you are paying attention while you read, 2) make sure you are understanding what you read and 3) find passages later when you are flipping back through.

If you find an important passage or important line, you can write something more detailed. Fortunately I did that for Book 1 and 2, so I had some things to talk about in my review. For Book 3, I’ve been notating it far more extensively, so it should be much easier for me to remember later and write about.