Now begins the Fifth Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation once a week from now until the announcement.

For those of you who don’t know how this works, check out the past four years:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

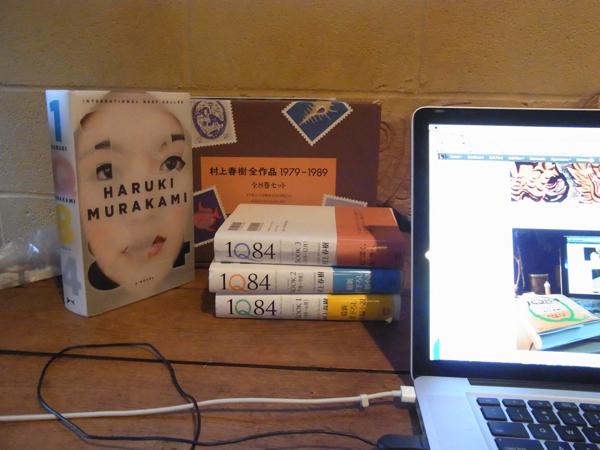

This year, as mentioned on Twitter, I’ll be taking a close look at Dance Dance Dance. Jay Rubin has detailed exactly how he abridged the translation of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle in his book Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, but I don’t think anyone has looked closely at how Birnbaum adjusted his translation of DDD which, rumor has it, also had cuts for publication abroad.

Sadly, I was not able to finish reading the book, so I can’t speak for the translation as a whole; there may be major cuts later in the novel that I’m not aware of, but in the first third of the novel, I was surprised to find only minor compression. I say “minor,” but to translation purists, these may seem like egregious changes. Some amount to Birnbaum’s somewhat fast and loose translation style that created the perfect tone for Murakami’s boku narrator, but others are longer and clearly made for editorial rather than stylistic reasons.

The first major excision comes at the end of Chapter 4. Boku arrives in Sapporo and decides to walk to the Dolphin Hotel from the station. He stops in a coffee shop and feels intensely out of place and lonely. Here is how Birnbaum renders the section:

Of course, by the same token, I couldn’t really say I belonged to Tokyo and its coffee shops. But I had never felt this loneliness there. I could drink my coffee, read my book, pass the time of day without any special thought, all because I was part of the regular scenery. Here I had no ties to anyone. Fact is, I’d come to reclaim myself.

I paid the check and left. Then, without further thought, I headed for the hotel. (21)

In Japanese, however, you can see that Birnbaum has cut the majority of five paragraphs and reconstituted them using the underlined sentences below (Note: I’ve added the underlining):

もちろん東京のコーヒー・ハウスでそのような激しい孤独を感じることはない。僕はコーヒーを飲み、本を読み、ごく普通に時を過ごす。何故ならそれはとりたてて深く考えるまでもない日常生活の一部だから。

しかしこの札幌の街で、僕はまるで極地の島に一人で取り残されてしまったような激しい孤独を感じた。情景はいつもと同じだ。どこにでもある情景だ。でもその仮面を剝いでしまえば、この地面は僕の知っているどの場所にも通じていないのだ。僕はそう思った。似ている―でも違う。まるで別の惑星みたいだ。言語も服装も顔つきもみんな同じだけれど、何かが決定的に違う別の惑星。ある種の機能がまったく通用しない別の惑星―でもどの機能が通用してどの機能が通用しないかはひとつひとつ確かめてみるしかないのだ。そして何かひとつしくじれば、僕が別の惑星の人間だということはみんなにばれてしまう。みんなは立ち上がって僕を指さしなじることだろう。お前は違うと。お前は違うお前は違うお前は違う。

僕はコーヒーを飲みながらぼんやりとそんなことを考えていた。妄想だ。

でも僕が孤独であること―これは真実だった。僕は誰とも結びついていない。それが僕の問題なのだ。僕は僕を取り戻しつつある。でも僕は誰ともむすびついていない。

この前誰かを真剣に愛したのはいつのことだったろう?

ずっと昔だ。いつかの氷河期といつかの氷河期との間。とにかくずっと昔だ。歴史的過去。ジュラ紀とか、そういう種類の過去だ。そしてみんな消えてしまった。恐竜もマンモスもサーベル・タイガーも。宮下公園に打ち込まれたガス弾も。そして高度資本主義社会が訪れたのだ。そういう社会に僕はひとりぼっちで取り残されていた。

僕は勘定を払って外に出た。そして何も考えずにいるかホテルまでまっすぐ歩いた。(45-46)

Here is how my version reads:

Of course I’d never felt that intense loneliness at coffee shops in Tokyo. I had my coffee, read my book, and otherwise spent time there as normal: it was a part of my daily life that I never had to think that deeply about.

In Sapporo, however, I felt as intensely lonely as a man set adrift on an Arctic island. Everything around me was the same as always, the same stuff you’d find anywhere. But if you peeled back the mask, I felt like it didn’t connect with any of the places I was familiar with. It resembled it…but something was different. It was like a completely different planet. A planet where everything was the same – the language, the clothes, the way people looked – but something was decisively different. A planet where some sort of function completely failed to translate – but the only way to know which functions translated and which didn’t was to check them one by one. And if I somehow messed up one of them, everyone would know that I was from a different planet. Everyone would stand up, point me out, and tell me off: You’re different. You’re different, you’re different, you’re different.

That’s what I was thinking about while I had my coffee. A total delusion.

But I was lonely – that was a fact. My problem was that I wasn’t connected to anyone. I had to recover myself. But I wasn’t connected to anyone.

When was the last time I had really loved someone?

Long, long ago. Sometime between the last two ice ages. At any rate, long, long ago. In the historic past. During the Jurassic period, that kind of historic past. Everything was gone. The dinosaurs, wooly mammoths, and saber tooth tigers – all of them. The poison gas tear gas fired into Miyashita Park as well. Then this advanced capitalist society came to town, and I’d been left all alone among it.

I paid the check and went outside. Then I walked straight to the Dolphin Hotel without thinking about anything.

It’s pretty easy to understand why Birnbaum decided to cut these sections: Murakami is just thinking/rambling through his narrator here, developing the intense sense of loneliness by expounding through metaphor, a technique that he used at the end of “The Twins and the Sunken Continent,” in which the narrator imagines being sunk on Atlantis while the twins fly off on a floating continent. It doesn’t advance the plot, nor the character, and I doubt that he returns to the image later in the novel (although that’s something I’ll have to keep an eye out for as I continue reading), other than the link to “advanced capitalist society,” which plays out a little. Still, there’s something fun about reading these sections – they feel like automatic writing, which I’m sure is how Murakami is able to generate some of the awesome imagery, metaphor, and absurdity that he comes up with.

One small editorial note: Miyashita Park is a park in Shibuya, and judging from this blog post, it was the site of protests back in the early 70s. The park’s inclusion here feels isolated and out of place, and it’s probably another reason Birnbaum cut it.

And one embarrassing language note: I’ve finally come to terms with the fact that みんな can mean “everything” not just “everyone” as I insisted in the comments to this post back in 2009. After getting some more reading reps with the word, this has become more clear, and my apologies go out to DBP. Remember, folks: pride doesn’t pay if you want to learn the language. Get over it, and get used to it.