Happy New Year, folks. Yoroshiku and all that jazz in 2015.

Apologies for the delay with the Hard-boiled Wonderland Project. Two more posts in Chapter 21 “Bracelets, Ben Johnson, Devil” and I’ll be finished with half of the novel. Here comes the fourth and penultimate post.

This chapter is starting to feel longer than it actually is—which is very long, at least in the original Japanese.

The Girl in Pink and Watashi continue their subterranean march. They make it into the INKling sanctuary and then begin their climb up the “mountain” to a plateau. Birnbaum makes some judicious cuts of lengthy introspection about fear, accomplishment, and life. This chapter is so long that Murakami himself also makes some cuts from the original text to the Complete Works version.

First, check out how Birnbaum handles the translation when the pair of them decide to kill time on their hike by singing:

From time to time she called out to make sure I kept pace. “You okay?” she’d say. “Just a little more.”

Then, a while later, it was “Why don’t we sing something?”

“Sing what?” I wanted to know.

“Anything, anything at all.”

“I don’t sing in dark places.”

“Aw, c’mon.”

Okay, then, what the hell. So I sang the Russian folksong I learned in elementary school:

Snow is falling all night long—

Hey-ey! Pechka, ho!

Fire is burning very strong—

Hey-ey! Pechka, ho!

Old dreams bursting into song—

Hey-ey! Pechka, ho!

I didn’t know any more of the lyrics, so I made some up: Everyone’s gathered around the fire—the pechka—when a knock comes at the door and Father goes to inquire, and there’s a reindeer standing on wounded feet saying, “I’m hungry, give me something to “eat”; so they feed it canned peaches. In the end everyone’s sitting around the stove, singing along.

“Wonderful. You sing just fine,” she said. “Sorry I can’t applaud, but I’ve got my hands full.”

We cleared the bluff and reached a flat area. …” (214 − 215)

I won’t bother you with the full Japanese of this section because Birnbaum’s translation is basically spot on. He translates the Japanese song “Pechka” in a pretty clever way, but I think it’s clear if you compare it with a performance of the original Japanese that Birnbaum is going for a more upbeat version:

雪の降る夜は

楽しいペチカ

ペチカ燃えろよ お話しましょ

昔々よ

燃えろよペチカ

(Although pechka is a Russian word, the song seems to be a Japanese original by songwriter Kosaku Yamada with lyrics by poet Hakushū Kitahara. Here’s another even more somber version, and if those link fails, there should be some other versions on YouTube.)

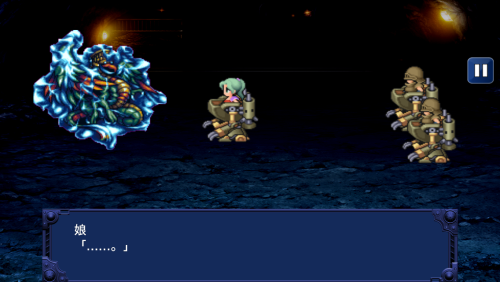

But other than that, there isn’t much worth commenting on…until Watashi finishes singing. As you’ll see in this next ENORMOUS section, Birnbaum has cut a number of songs from the translation, and Murakami also makes some cuts. I’ve marked cuts Murakami made in the Complete Works version in red and provided the slightly altered intro to the Girl in Pink’s song in parenthesis. The original text contains all of the following:

「なかなかうまいじゃない」と彼女がほめてくれた。「握手できなくて悪いけど、すごく良い唄ね」

「ありがとう」と私は言った。

「もう一曲唄って」と娘が催促した。

それで私は『ホワイト・クリスマス』を唄った。

夢みるはホワイト・クリスマス

白き雪景色

やさしき心と

古い夢が

君にあげる

僕の贈りもの

夢みるはホワイト・クリスマス

今も目を閉じれば

橇の鈴の音や

雪の輝きが

僕の胸によみがえる

「とてもいいわ」と彼女が言った。「その歌詞はあなたが作ったの?」

「でまかせで唄っただけさ」

「どうして冬や雪の唄ばかり唄うの?」

「さあね。どうしてかな?暗くて冷たいからだろう。そういう唄しか思いつかないんだ」と私は岩のくぼみからくぼみへと体をひっぱりあげながら言った。「今度は君が唄う番だよ」(「次は君が唄う番だ」)

「『自転車の唄』でいいかしら?」

「どうぞ」と私は言った。

四月の朝に

私は自転車にのって

知らない道を

森へと向った

買ったばかりの自転車

色はピンク

ハンドルもサドルも

みんなピンク

ブレーキもゴムさえ

やはりピンク

「なんだか君自身の唄みたいだな」と私は言った。

「そうよ、もちろん。私自身の唄よ」と彼女は言った。「気に入った?」

「気に入ったね」

「つづき聞きたい?」

「もちろんさ」

四月の朝に

似合うのはピンク

それ以外の色は

まるでだめ

買ったばかりの自転車

靴もピンク

帽子もセーターも

みんなピンク

ズボンも下着も

やはりピンク

「ピンクにたいする君の気持ちはよく分かったから、話を先に進めてくれないかな」と私は言った。

「これは必要な部分なのよ」と娘は言った。「ねえ、ピンク色のサングラスってあると思う?」

「エルトン・ジョンがいつかかけていたような気がするな」

「ふうん」と彼女は言った。「まあいいや。つづき唄うわね」

道で私は

おじさんに会った

おじさんの服は

みんなブルー

髭を剃り忘れてるみたい

その髭もブルー

まるで長い夜みたいな

深いブルー

長い長い夜は

いつもブルー

「それは僕のことかな?」と私は訊いてみた。

「いいえ、違うわ。あなたのことじゃない。この唄にあなたは出てこないの」

森に行くのは

よしたがいいよ、あんた

とおじさんは言う

森のきまりは

獣たちのためのもの

それがたとえ

四月の朝であったとしても

水は逆に流れたりはしないものだ

四月の朝にも

それでも私は自転車で森へ向う

ピンクの自転車の上で

四月の晴れた朝に

こわいものなんて何もない

色はピンク

自転車から降りなければ

こわくない

赤でもブルーでも茶でもない

まっとうなピンク

彼女が『自転車の唄』を唄い終えた少しあとで、我々はどうやら崖をのぼりきったらしく、広々とした台地のようなところに出た (377-382)

“You’re pretty good,” she said, complimenting my singing. “I’m sorry I can’t clap for you. That was a great song.”

“Thanks,” I said.

“Sing one more,” she prodded.

So I sang “White Christmas.”

I’m dreaming of a White Christmas

With white snowy scenes

A gentle heart

And old dreams

Are the present

I give to you

I’m dreaming of a White Christmas

Even now when I close my eyes

The ring of the sleigh bells

And the bright snow

Fill my heart with memories

“That was nice,” she said. “Did you make up those lyrics?”

“I just sang it randomly.”

“Why do you only sing songs about winter and snow?”

“Dunno,” I said. “Wonder why. Maybe it’s so cold and dark down here those are the only songs I can think of.” I dragged myself from hole to hole in the boulders. “Now it’s your turn to sing.” (“Next it’s your turn to sing.”)

“Is it okay if I sing ‘The Bicycle Song’?”

“Sure,” I said.

On an April morning

I got on my bicycle

And headed into the woods

Down a strange path

I’d just bought the bike

And it was pink

The handlebars and seat too

Everything was pink

Even the brakes and the tires

They were all pink

“You’ve really captured your spirit with this song,” I said.

“Yes, of course,” she said. “It’s my song. Do you like it?”

“I do.”

“Do you want to hear the rest?”

“Of course.”

On an April morning

Pink suits me

All other colors

Are no good

My brand-new bike

My shoes were pink

My helmet and sweater too

Everything was pink

My shorts and underwear too

They were all pink

“I’m starting to understand how you feel about the color pink,” I said. “Do you think you could move the story along a little?”

“This part is necessary,” she said. “Hey, do you think they have pink sunglasses?”

“I feel like Elton John has probably worn some at some point.”

“Hmm,” she said. “Ok. I’ll sing the rest.”

On the road

I met an old man

All of the man’s clothes

Were totally blue

He’d also forgotten to shave

And his beard was blue

A deep blue

Like a long, lonely night

Long, long nights are

Always blue

“Is that me?” I asked.

“No, it’s not. It’s not about you. You aren’t in this song.”

Hey you

You shouldn’t go to the woods

The old man said

The rules of the woods

Are for the beasts

And even on an April morning

Water won’t flow in the opposite direction

Even on an April morning

But I still headed for the woods

On my pink bicycle

On a clear April morning

There was nothing that could scare me

And if I never got off my bicycle

That was the color pink

I wouldn’t be scared

Not red or blue or brown

But proper pink

Shortly after she finished singing “The Bicycle Song,” we appeared to clear the bluff and come to a wide open plateau-like area.

I’ve translated the songs pretty literally without much attention to poetics or anything, so I’m sure there are some places that make the Japanese original seem even stranger than it actually is, but WHAT was Murakami thinking with this passage? I mean, he writes it himself: Do you think you could move the story along a little?

My best guess is that Murakami wasn’t thinking when he wrote these sections and that they are examples of his writing style, unadulterated by any editing whatsoever. It’s clear that he’s trying to use them to connect Watashi’s world with Boku’s—there’s the snow, woods, reindeer (which are kind of like unicorn, right?), and beasts—but it’s just too indirect and never goes anywhere. Far too random to be anything but annoying additions that Japanese readers have to slog through. Ugh. And Murakami only chose to cut “White Christmas” in his edited version!

I’m not sure if there’s anything else to mention about this passage other than that Birnbaum’s cuts are significant improvements.