Well, my 1Q84 review is online. I can’t say enough about the guys at Néojaponisme. They did a fantastic job helping me turn my thoughts on 1Q84 into a cohesive article. Major props to Matt over at No-sword.

This is as good a time as any to give a postmortem on my 1Q84 predictions and add a few thoughts about the book. Some very vague spoiler-ish type material is included, but nothing too critical; still, read at your own risk.

Prediction 1: It’s going to be a monster.

Verdict: Yes

This was a gimme prediction. I needed one to guarantee I didn’t embarrass myself with a bagel. At 1055 pages it’s gigantic, but we all knew that going in; that was one of the few things Murakami DID reveal about the novel. Ben Dooley at The Millions noted that The Wind-up Bird Chronicle is longer, but only when you take into account Wind-up Bird’s belated third volume. It still only edges out 1Q84 by a meager 100 pages or so. If Murakami adds a third volume to 1Q84, it will easily crush Wind-up Bird.

That said, unless Murakami adds a 700 page third volume with 20 new characters and lots of action, Wind-up Bird will still feel longer. There are more characters and more things happen. And there are no coddamn “Little People” in Wind-up Bird (this will make more sense in a few years). 「ほうほう」と俺が言う。

Prediction 2: He will not re-work a previous short story or novel.

Verdict: Yes

Alright! I’m really happy I got this right, but as mentioned in the prediction, I was hoping he would incorporate something old. Using old material forces him to edit and refine. He’s had a lot of success with that technique (Hard-boiled Wonderland, Norwegian Wood, Wind-up Bird, Sputnik Sweetheart), perhaps because it’s the only form of editing he’s getting. In a college class, I once heard a professor compare the relationship between author and editor in Japan to one of sensei and student – the editor accepts the manuscript from the writer and thanks him deeply before taking it straight to the press.

And this book feels like it could lose some weight. If, say, it had been edited down into one volume, then he could have written a kick-ass second volume to wrap things up. But he takes his sweet time, dragging six months of calendar time in the novel out over 1000 pages.

Prediction 3: World War II will be a theme.

Verdict: No

What a terrible call. The answer was sitting there right in that section of the article I quoted, but I didn’t realize it. Murakami does not use WWII as a theme, but he does use religious cults as a theme. Yes, there is one section in the novel where WWII is mentioned, but it’s brief, not fully connected to other sections of the novel, and there is nothing about the brutality of Japanese soldiers in the Pacific. More about the cult topic below.

Prediction 4: It’s going to be great.

Verdict: No

Well, points to me for being optimistic, but this is not one of Murakami’s better works. I think it’s clear from the beginning of my review that Murakami’s best year was 1985. That five-year period from ’82 to ’87 (A Wild Sheep Chase to Norwegian Wood) is just incredible, and ’85 is, in retrospect, the peak. For whatever reason, his post-Norwegian Wood novels have been all over the place, including Wind-up Bird. That’s one thing 1Q84 did to me – it has changed my opinion of Wind-up Bird. I remember enjoying it the two times I read it, but looking back at it through this most recent novel, it seems more like an unstable collage of randomness, not unlike Kafka on the Shore. In all three novels, there are discussions of WWII that don’t really fit in with the rest of the novel. Wind-up Bird is the strongest of the three, but it’s nowhere close to Hard-boiled Wonderland in terms of construction. Murakami’s technique seems to be much stronger on a smaller scale, like afterdark or A Wild Sheep Chase. Hard-boiled Wonderland seems to be an exception since he had to revise an old work and admittedly rewrote the ending after his wife didn’t like it. (Rubin mentions this on page 115 of his book, referring to the supplement to the Complete Works).

Prediction 5: There will be a flush of short stories later this year.

Verdict: Unknown

We’ll have to wait and see what he produces next, but I imagine that he’s already at work on something. He’s a machine.

Prediction 6ish: The Aum attack will be a theme.

Verdict: Kind of.

After seeing Dmitri Kovalenin’s livejournal and his commenter’s research showing that 1Q84 is some kind of weird gene-thing, I brought up the fact that the Aum attack could be a topic. Well, cults definitely take up a good part of Book 1, but not for the reason we thought – sarin gas has nothing to do with the book. So I’m giving myself half a point here. It seems like Murakami tries to address the cult mindset, combine that with the idea of a similarly powerful groupthink situation, and the fuck everything up with some weird fucking moral quandary (that involves baby-raping, no less). (Yes, baby-raping. Well, more like statutory “rape.” But that can be our little secret until the translation comes out.)

The cult theme, however, gets dropped for the most part in Book 2, so I guess this should really only be a quarter of a point, which means…

2.25/5 = EPIC FAIL! (Although I could end up 3.25/6 depending on how his short stories pan out.) Oh well. It was fun. It pains me even to think it, but Murakami may be losing a step. But hey hey hey, don’t think about that, let’s look at one of his old short stories!

“The Twins and the Sunken Continent” is a great little short story. It was almost unreal to sink back into that same mellow tone courtesy of Murakami’s infamous boku. I started reading the story a year and a half ago but didn’t get around to finishing it until earlier this year. Some bloggy blog blog type thoughts:

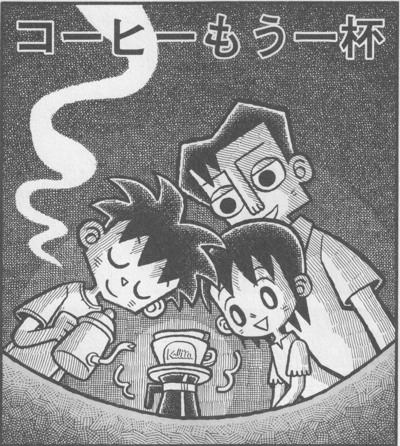

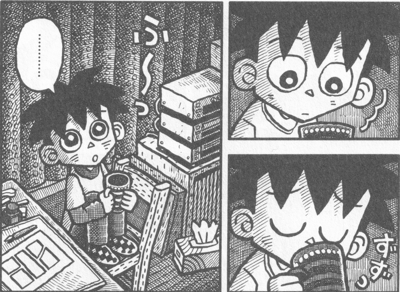

– There’s this amazing scene where boku has returned to his office after seeing the photo of the twins. The place is a mess, but before he starts cleaning he chills out with a cup of coffee that he is forced to stir with a pen because the spoons are dirty. Such a simple scene, but it’s one of my favorite parts of the story, I think because the physical mess of the office mirrors his mental confusion, and he just kind of sits with it for a few moments, quietly enjoying a cup of coffee, before he begins to pick up the pieces.

– I’ve always been jealous of how Murakami narrators can just throw down their cups of coffee. The boku here has one at a cafe, and then two more, maybe three, in short order back at the office. And if he was visiting a client, you can bet that they probably served him a cup, too! Hard-boiled Wonderland has that great scene where he drinks a thermos of coffee and eats sandwiches with the old scientist. I start twitching after two cups and then go into an extreme crash an hour or two later, which is why I normally drink coffee in the afternoons, tea in the morning. Sometimes I wish I could drink coffee like boku, but maybe it’s healthier that I can’t.

– I find it very interesting that Murakami decided to write about his old boku after writing Hard-boiled Wonderland. As mentioned in the article, he wanted to go back and see the character again (along with the Sheep Man) after finishing Norwegian Wood (which resulted in Dance Dance Dance). “The Twins and the Sunken Continent” shows that it wasn’t just a one time thing. For the first 10 years of his career, it was a pattern that mirrors the way he goes from long novels to short stories.

– Loss is the main theme that this story shares with 1Q84. It’s kind of spooky how similar the language is. In both case he’s using 失われている. It’s a stranger choice of words in 1Q84, and I think Murakami uses it purposefully to stand out. It will be very interesting to see how it gets translated. In “The Twins,” it’s much more natural.

– Also interesting that Murakami uses the Sun and the Moon as his poles of reality in “The Twins.” In 1Q84, there is a very similar metaphor at play, and a change in the poles signifies a drastic change in reality.

– The dream discussion sequence is also classic Murakami – a character desperately trying to use language to explain something that is totally unreal but vital. If you look back through his works, I’m willing to bet that every single one uses storytelling in this way somehow. This is probably why he’s so much stronger in the first person – Murakami, I think, has strong doubts about the ability of language to accurately describe reality, or unreality, but that struggle is interesting, and it’s something that almost all of us have experienced at some point.

– There’s also an interesting music connection that I failed to mention in the review. In 1Q84, Bach’s “The Well-Tempered Clavier” comes up, and actually the novel itself is structured in the same way – two volumes of twenty-four. (Someone far smarter than I am will explain what this means. A scary thing to think about is the fact that there are actually 96 pieces of music in “The Well-Tempered Clavier” – both prelude and fugue for each major and minor key. Is Murakami going to write another 1000 pages?) In “The Twins,” boku puts on a piece of lute music by Bach as he cleans his office.

– Reading this story, I got the feeling that the twins weren’t real people. They seem much closer to Murakami’s poor aunt from the story “A Poor-Aunt Story” – a physical representation of an emotional state, one that is different for everyone. Rubin argues that the poor aunt stands for “everything unpleasant that we push out of our minds by subtly suggesting things we ought to know but have managed to suppress” (Rubin 60). (There must be some long German word that has the exact same meaning. Anyone? Bueller?) The twins, then, represent an idealized past, one that is lost and can never be reclaimed. Life with the twins was easy – boku had a pleasant life at home uncomplicated by sex; simply compassion and warmth. The twins with another man look different because to that man the situation that makes him feel the same as boku did is different. The two of them feel the same emotion, but they require different input for them to get to that emotion. The twins are the physical representation of that emotion.

On second thought, they could also represent a point in life where one is finally comfortable being alone (but lonely) in the world, assuming that the twins weren’t real people and that boku was living alone. This may require further more sober contemplation.

とりあえず、以上です。

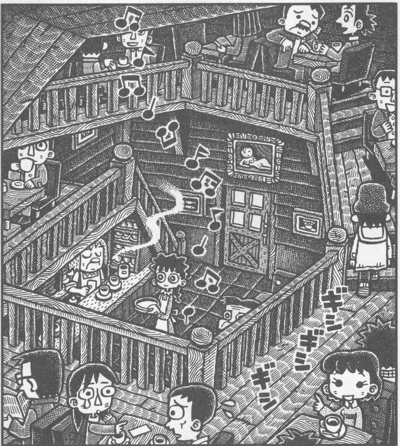

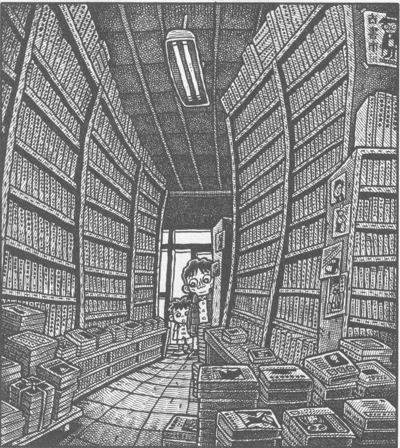

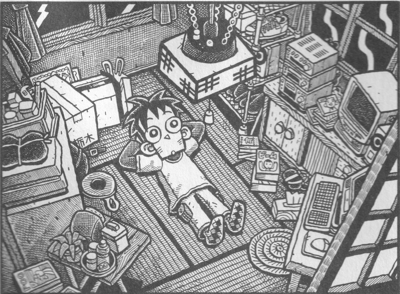

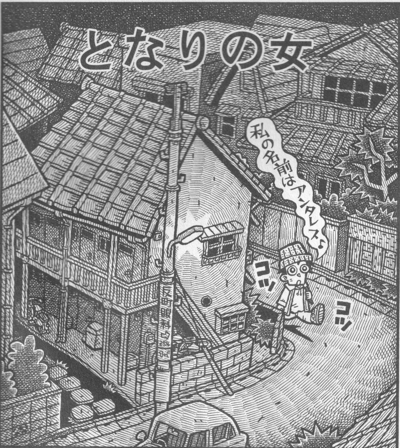

(Graphic courtesy of Ian Lynam and Neojaponisme.)