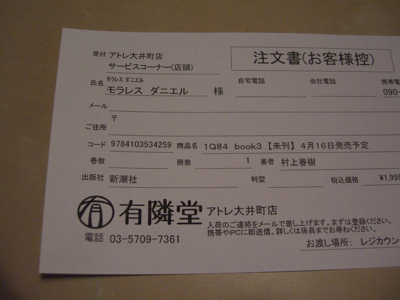

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and mid-October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of unpublished Murakami translation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see the other entries in this series here: 1, 2, 3.

Last week I showed you a passage from a Birnbaum translation that had missing sentences. This week it’s Rubin’s turn to go under the magnifying glass. Here is a section of his official translation of Norwegian Wood:

Three old women were the only passengers on the Sunday morning streetcar. They all looked at me and my flowers. One of them gave me a smile. I smiled back. I sat in the last seat and watched the old houses passing close by the window. The streetcar almost touched the overhanging eaves. The laundry deck of one house had ten potted tomato plants, next to which a big black cat lay stretched out in the sun. In the yard of another house, a little kid was blowing soap bubbles. I heard an Ayumi Ishida song coming from someplace, and could even catch the smell of curry cooking. The streetcar snaked its way through this private back-alley world. A few more passengers got on at stops along the way, but the three old women went on talking intently about something, huddled together face-to-face.

I got off near Otsuka Station and followed Midori’s map down a broad street without much to look at. None of the shops along the way seemed to be doing very well, housed as they were in old buildings with gloomy-looking interiors and faded writing on some of the signs. Judging from the age and style of the buildings, this area had been spared the wartime air raids, leaving whole blocks intact. A few of the places had been entirely rebuilt, but just about all had been enlarged or repaired in spots, and it was those additions that tended to look far more shabby than the old buildings themselves.

The whole atmosphere of the place suggested that most of the people who used to live here had become fed up with the cars and the filthy air and the noise and high rents and moved to the suburbs, leaving only cheap apartments and company flats and hard-to-move shops and a few stubborn holdouts who clung to family properties. Everything looked blurred and grimy as if wrapped in a haze of exhaust gas.

Ten minutes’ walk down this street brought me to a corner gas station, where I turned right into a short block of shops, in the middle of which hung the sign for Kobayashi Bookstore. True, it was not a big store, but neither was it as small as Midori’s description had led me to imagine. It was just a typical neighborhood bookstore, the same kind I used to run to on the very day the boys’ magazines came out. A nostalgic mood overtook me as I stood in front of the place. (Rubin, 64-65)

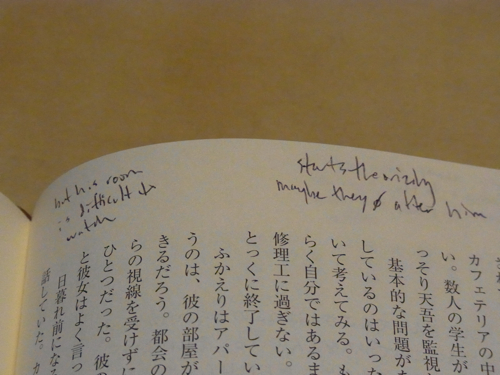

The final paragraph is the only one with missing lines, but I love this section of the book (partly because I love the neighborhood and the streetcar line) and wanted to give some of the development to the missing sentence. In the passage, the protagonist Toru makes his way to Midori’s family-run bookstore. She lives near Otsuka Station, a short ride on a streetcar (in reality the Arakawa Toden line that arcs northeast from Waseda through Otsuka and then down into Arakawa Ward) from Waseda University, the college Murakami attended and used as a model for the university in the novel. As Toru rides the streetcar to visit her he is assaulted by an array of sensory input. But Rubin leaves out the final sentence of the last paragraph, which in Japanese is:

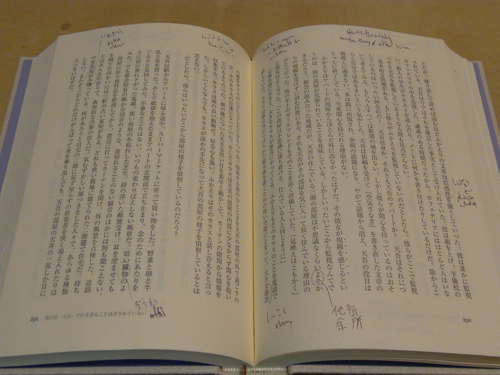

どこの町にもこういう本屋があるのだ。(全作品, 98)

Norwegian Wood is one of the few works that has been translated into English by two different people, so we have the perfect opportunity to see two different sets of translation choices (by professionals, rather than my lousy efforts). In his translation for Kodansha International, Alfred Birnbaum renders this same section like this (I have bolded the additional sentence.):

The Sunday morning streetcar was passengerless except for a group of three old ladies, who sized up me and my narcissuses. One lady smiled at me. I smiled back and took a seat at the back to watch the old houses swing past. At times the streetcar practically scraped the eaves. Here a glimpse of ten potted tomato plants on a platform for hanging laundry, where a cat lay sunning itself, there children blowing soap bubbles in a back yard. Somewhere an Ayumi Ishida tune was playing. The smell of curry drifted by as the streetcar threaded an intimate course through the backstreet neighborhoods. A few more passengers boarded at stops en route, scarcely noticed by the old ladies, who huddled together, tirelessly chatting away.

I got off near Otsuka Station and followed Midori’s map down a singularly unremarkable main street. None of the shops along the way seemed to enjoy much turnover. All the stores were old and dark inside. The characters on some signs were not even legible any more. I could tell from the age and style of the buildings that this area hadn’t been bombed in the war. That’s why these shops were still there. Additions and partial repairs only made the buildings more dilapidated.

Most people had left the area to escape the cars and smog and noise and high rents, leaving behind only run-down apartments and company housing and businesses that proved difficult to uproot, or else locals who stubbornly stuck to their longtime residences and refused to move. A haze hung over the place, probably from car exhaust, making everything seem vaguely dingy.

A ten-minute walk down desolation row, I came to a corner gas station, where the map had me turn right into a small shopping street, and midway down that I made out the Kobayashi Book Shop sign. Not a very big bookstore, granted, but not quite as small as I’d imagined from Midori’s description. Your ordinary everyday neighborhood bookstore. The kind of bookstore I’d run to as a boy to buy that latest, anxiously awaited kiddy-zine the day it hit the stands. Somehow, just standing in front of the Kobayashi Book Shop made me feel nostalgic. Surely every town (町) must have a bookstore like this. (Birnbaum 1, 125-126)

The sentence is a throwaway detail, but it does include the Japanese 町, which I wrote about briefly after my thesis rewrite went up on Neojaponisme. In Murakami’s early work, the 街 (まち, machi) is a central theme. Machi literally means town, and Murakami uses it in his early novels to refer to the place where the narrator, the legendary boku, grew up. All of his past is tied up with the machi and it exerts a certain level of control over him because it is where all his memories come from. From Hear the Wind Sing to A Wild Sheep Chase, boku goes through a process of growth into adulthood and a separation from his hometown. He eventually forsakes it, cutting ties with the past and looking toward the future. Nothing is ever named, but the machi strongly resembles Kobe, Murakami’s own hometown.

In Norwegian Wood, both boku and the machi have names, and perhaps this is why Murakami chose 町 rather than the 街 as in his early works. Boku is Toru Watanabe, a student in Tokyo during the turbulent late-60s. Toru is not dissimilar from the old boku. He has the same tastes in music and literature and he spends his time reading novels and watching movies instead of participating in political demonstrations or study groups with activists who are caricatured throughout the novel. The machi in this novel is Kobe, also similar to the machi from the first three novels. Toru grew up there, but when his best friend Kizuki commits suicide he starts to feel a desire to leave. Toru says “I had to get away from Kobe at any cost,” and shortly after that notes “I just need to get away from this town (machi)” (Rubin 24-25). Toru “escapes” Kobe for Tokyo in the same way that the boku from Murakami’s first three novels escapes the anonymous machi for Tokyo.

Escaping to Tokyo also gives Toru the opportunity to establish his own emotional center to the world, a new place that will have new memories associated with it. But it isn’t that easy. The machi he finds after moving to Tokyo are divided, most notably by the two female protagonists. Rubin has noted how Naoko and Midori represent a dichotomy between life and death (Rubin, Music of Words 159). This is further represented by the “machi” they inhabit. Naoko, after a break down, flees from Tokyo to a regimented, sterile sanatorium deep in the hills of Kyoto. Midori’s machi is the opposite – although old and somewhat grimy, it is filled with different smells, sounds and flavors. It’s strongly connected to Toru’s own past (as well as Japan’s collective history), which might explain why he seems confused when talking to Midori at the end of the book; Toru’s process of self-discovery has lead him from his machi hometown to Tokyo, out to the isolation of Naoko’s sanatorium, back to the chaos of late-60s Tokyo, off wandering after Naoko’s death, and then after all of this he still doesn’t know where he is. Judging from the tone of the novel, his attempts to return to Midori and her familiar (nostalgic) machi must have been futile. Otherwise why write the book? The novel’s final, hopeless line is:

僕はどこでもない場所のまん中から緑を呼びつづけていた。(全作品, 419)