It’s finally time – here are my Murakami Novel Power Rankings! I spent the last two months re-reading Murakami’s novels, and I feel prepared to put them in order from least successful to most successful. Obviously this is a subjective exercise, but I would also argue that this is the correct order.

Even as recently as a year or two ago, I would have had my personal favorite Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World at the top of the list, so regular readers may be surprised to learn that it is not. Take a listen to see where I ranked it.

One thing that became clear to me while re-reading these novels is that the central dynamic in Murakami’s writing is immediacy vs controlled narration. He often puts the reader in the driver seat with the narrator, following them around during routines or waiting long periods of time for something to happen. I’ve noticed this a lot in genre fiction, which I think may partially explain why Murakami has a ravenous following and why many readers love books like Kafka on the Shore, which I would argue over rely on immediacy to generate reader interest.

Many readers are looking for that kind of experience, of following around a character having weird experiences. But I think there’s an exhaustion in this technique, which even Murakami himself recognizes. He has the instinct to vary this, even in his earliest novels; in Pinball, 1973 he alternates between the immediacy of the Rat’s experience struggling with life with more controlled narration of his Boku narrator’s implied grief for the loss of Naoko. Kafka also gets this alternating treatment as well as Hard-boiled Wonderland, and in both cases one half of the narrator is steeped in immediacy while the other has more controlled narration.

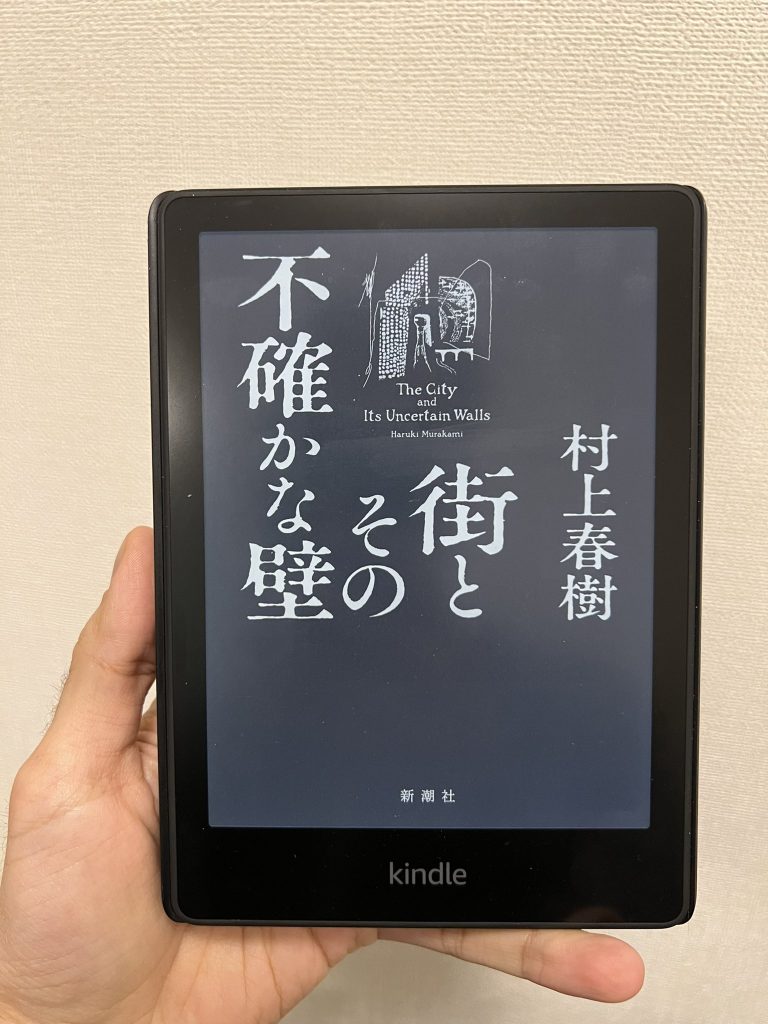

Given that Murakami is likely delivering an extension of Hard-boiled Wonderland next month, it will be very interesting to see what choices he makes with immediacy in the book and whether he decides to vary the narration as he did in 1985.