With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see past entries in the series here.

On to Chapter 8. We’re back in the End of the World, and we’re with Boku at his residence where he’s playing chess with the Colonel.

(On a ridiculous side note far too early in this blog post, I’ve always wondered if the Colonel was, by any chance, inspired or influenced by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, notably El coronel no tiene quien le escriba, which is a story about a poor, retired colonel waiting to receive his pension.)

No major cuts, additions, or revisions in this section, but I will take a look at a few places where Birnbaum uses his standard operating procedure.

While they play chess, Boku asks the Colonel about the Town and the Gatekeeper and meeting up with his shadow. Eventually, he asks, “Yet what does he have to fear from me?” (84)

The Colonel pauses and then says, in Japanese:

「君と君の影くっついてしまうことを心配しているんだよ。そうなるとまたはじめからやりなおしということになるからね」(120)

Birnbaum’s translation:

“He fears that you and your shadow will become one again” (84)

He cuts the second sentence, which should be something like:

“If that happens, he’d have to start over again from the beginning.”

Not a very substantial line, but it is a little more ominous than the official translation allows. It might be the first implication that there’s a point to the separation process, a goal that the Gatekeeper has in mind. Sure, the Gatekeeper’s been gruff and basically wouldn’t admit that he’d let Boku see the shadow, but there was no threat of death to the shadow, or even of a finality of a process. An interesting little line to cut.

[Rubin’s version:

“He’s worried that you and your shadow will get back together. If that happens, he has to do the whole thing over from scratch.” (84)

]

In the next section, Birnbaum has, I think, nicely rendered a metaphor that otherwise would have been awkward in English. Here’s the translation first:

“These next few weeks will be the hardest for you. It is the same as with broken bones. Until they set, you cannot do anything. Believe me” (85)

In Japanese, Murakami writes:

「ここのしばらくが君にとってはいちばん辛い時期なんだ。歯と同じさ。古い歯はなくなったが、新しい歯はまだはえてこない。私の意味することはわかるかね?」 (121)

My translation:

“The first little while will be the hardest part for you. Same as with teeth. Your old teeth have fallen out, but the new ones haven’t grown in yet. You get what I mean?”

I feel like a smoother translation might incorporate “baby teeth” somehow, but I’m not sure. At any rate, the broken bones metaphor feels much more natural, and while it may be more of a “localization” than a translation, I guess it works. What do y’all think?

[Rubin’s version:

“The next little while is going to be the toughest for you,” he said. “It’s like teeth. You’ve lost your old teeth but the new ones haven’t grown in yet. Do you see what I’m saying?”

]

And I have to point out cuts in the final paragraph of the chapter again. Birnbaum (or possibly his editor at Kodansha International?) makes strategic cuts to the final lines to create an in media res ending. Check out the translation:

“Good move,” says the Colonel. “Parapet guards against penetration and frees up the King. At the same time, it allows my Knight greater range.”

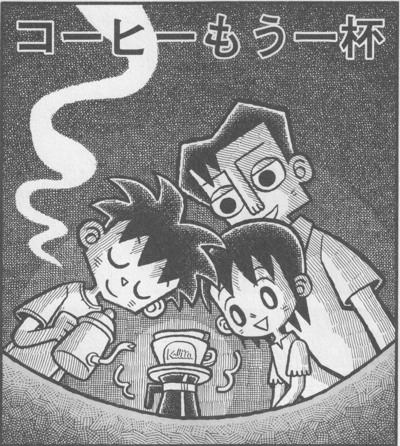

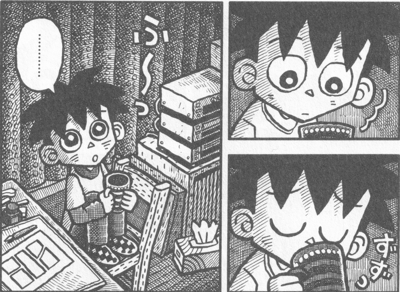

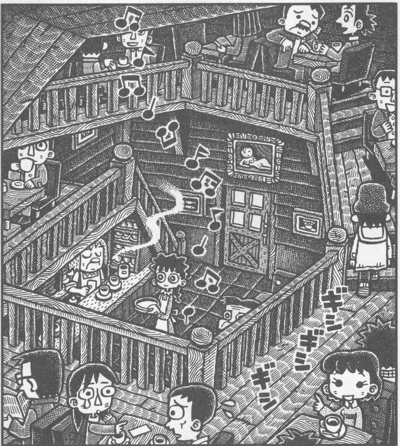

While the old officer contemplates his next move, I boil water for a new pot of coffee.

And the original text:

「上手い手だ」と老人は言った。「壁で角を防げるし、王も自由になった。しかしそれと同時に私の騎士も活用できるようにもなったな」

老人がじっくりと次の手を考えているあいだに僕は湯をわかし、新しいコーヒーをいれた。数多くの午後がこのように過ぎ去っていくのだ、と僕は思った。高い壁に囲まれたこの街の中で、僕に選びとることのできるものは殆ど何もないのだ。

You can see from the size of the second paragraph alone that there’s a lot of additional text in Japanese. I’ll add my translation of it to Birnbaum’s first line:

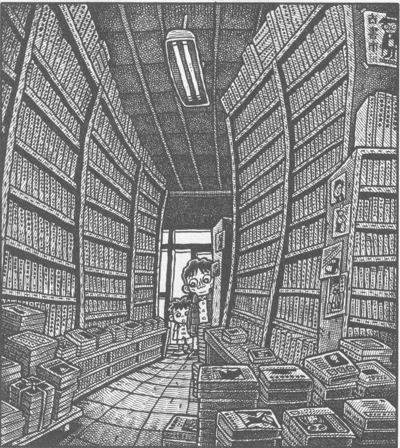

While the old officer contemplates his next move, I boil water for a new pot of coffee. Countless afternoons must pass this way, I think to myself. There is almost nothing for me to choose here in the Town surrounded by the tall Wall.

I was tempted to get fancy with that last line and write something like this: “There’s almost nothing arbitrary” or something like that. Or maybe “There’s nothing left for me to decide in the Town surrounded by the insurmountable Wall.” But no matter how you render it, nothing is quite as good as ending with Boku going for another pot of coffee. I’ve mentioned the importance of coffee in previous blog posts, and here again it serves to connect the two parts of the story and to suggest an endlessness to the End of the World.

[Rubin’s version:

“Good move,” the old man said. “You’ve blocked my horn with your wall and freed up your king. But at the same time, you’ve also given my knight a chance to move.”

While he gave careful thought to his next move, I boiled water and made a new pot of coffee. Lots of afternoons will go by like this, I thought. I have almost nothing to choose from in this town surrounded by its high walls.

]

And I guess one final interesting point in the section is Birnbaum’s decision to name the chess piece “Parapet” instead of “Wall.” I like the word choice, which sounds much more like a board game piece, but I don’t like how it dissociates it with the Wall that surrounds the town. It doesn’t matter as much in translation, however, since Birnbaum cuts the last line.

Some very interesting parts of a small chapter.

[Rubin’s translations added on 2025.09.07.]