I’m in the Japan Times this week with a look at some cool websites that help you define the differences in Japanese words: “使用? 利用? Make use of a dictionary to use your Japanese properly.”

It’s always good to start reading Japanese explanations of things as soon as you are able. The Wool vs. Cashmere explanation is a good example of something that’s pretty interesting, and perhaps not as dull as grammatical explanations.

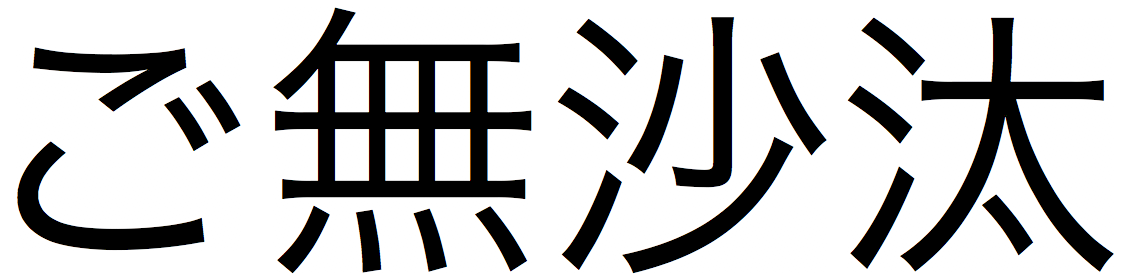

But we need the dull grammatical explanations, too! This is always a good reminder that the 日本語文型辞典 is an awesome resource. Here’s the full quote from the section I cite about the difference between なければならない (nakereba naranai, must) and なければいけない (nakereba ikenai, must):

「なければならない」「なくてはならない」は社会常識やことがらの性質から見て、そのような義務・必要性があるという意味を表す。つまり誰にとってもそうする義務・必要性があるという一般的な判断を述べる場合に用いられることが多い。これに対して「なければいけない」「なくてはいけない」は個別の事情で義務や必要が生じた場合に用いられることが多い。「なければだめだ」「なくてはだめだ」も同様であるが、「なければいけない」「なくてはいけない」よりもさらに話しことば的。

「なければ」の代わりに「ねば」、「ならない」の代わりに「ならぬ」を使うさらに書きことば的な言い方もある。

However, it’s one thing to read these and another thing entirely to put them into practice. The best advice I can give there is to write out a few example sentences of your own, ideally based on some Google sleuthing, and then mindfully attempting to incorporate them into daily usage.

Lately I’ve noticed that Google sleuthing for native phrases isn’t as helpful as it used to be. The Google algorithm seems to be focusing on webpages explaining the phrases rather than random sites that use the phrases.

I’ve been relying far more on Twitter sleuthing, which has been providing excellent results. Let’s see what we can find with the examples above.

A search for なければならない, for examples, gives this example from the great Count Okuma of Waseda University fame:

若い人は高尚な理想を持たなければならない。そしてそれを行う勇気がなければならない ~ 大隈重信 pic.twitter.com/mO3CZN5gsz

— 名言 (@meigen_dic) April 7, 2019

A loose translation of his quote: The young must hold lofty ideals. And they must have the courage to put them into practice.

Definitely seems worthy of social obligation/necessity.

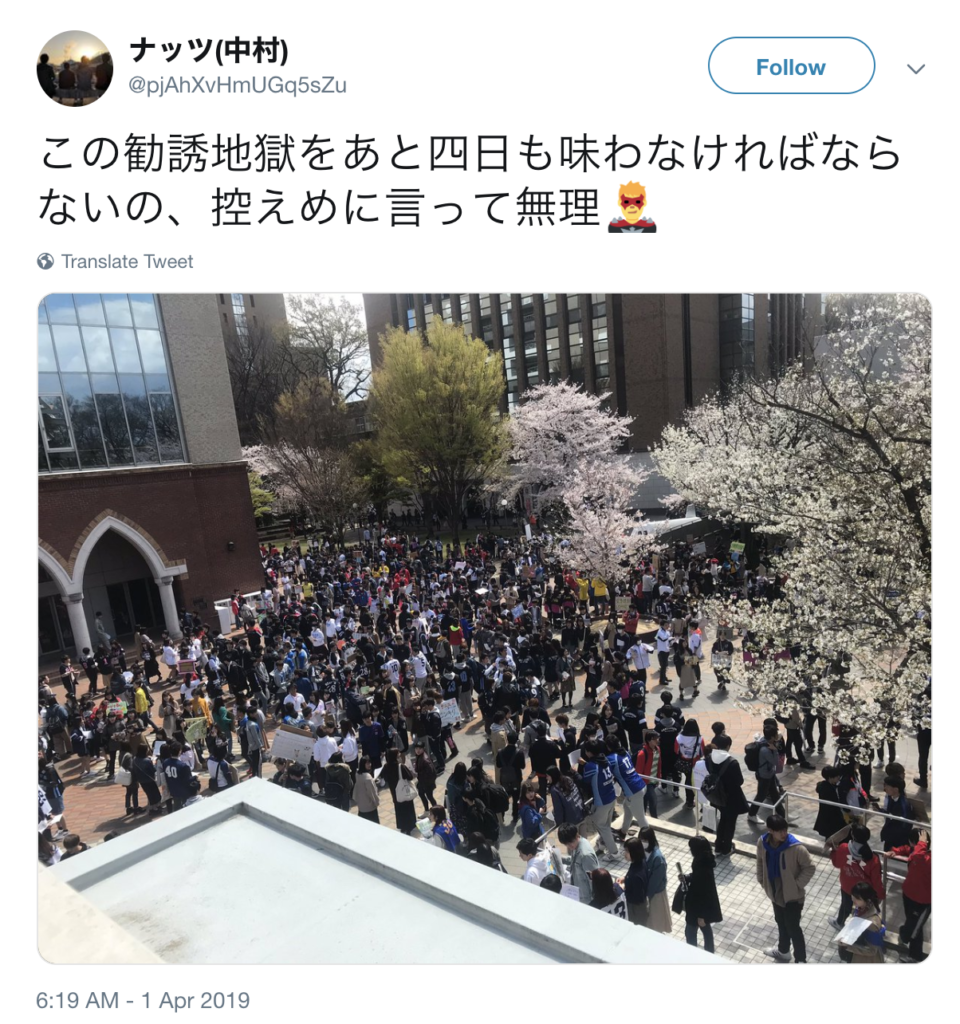

I found one result of this pattern from an account that seems to have gone private, but I left the tweet open in a tab for so long that I was able to screenshot it:

Coincidentally this is also university related—it’s the beginning of the term there, and the clubs are all out in force inviting frosh to join. One upperclassman has had enough:

Another good example of the fact that everyone has to suffer this 勧誘地獄 (kanyu jigoku, solicitation hell), which is one of my new favorite Japanese terms.

On the other hand, the user B太郎 has to have his morning fried chicken from Family Mart and expresses this individual necessity using なければいけない:

B太郎たるもの、朝はファミチキじゃなければいけない。 pic.twitter.com/KLhAOh0B7N

— B太郎 (@Btarou_style) April 6, 2019

Another user desperately needs some sleep:

ねなければいけないなぁ pic.twitter.com/AfJVAJekuP

— 缶 (@723_kn) April 5, 2019

I think this shows that Twitter is a pretty reliable source for native phrases. Are there any other sites you use? Maybe blog sites? Anything else?