Welcome to the Tenth Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see past entries in the series here:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter

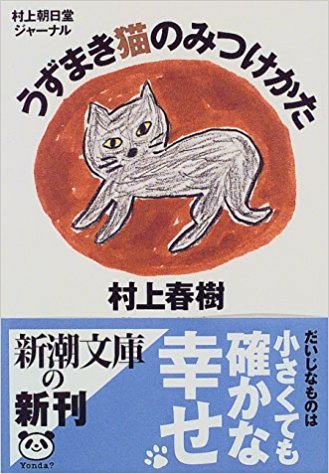

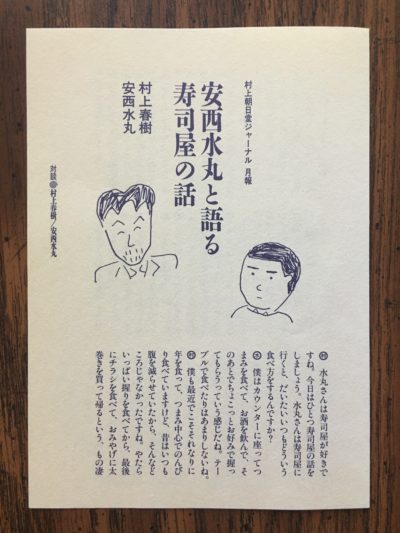

Today I’m looking at one last section of a conversation between Murakami and Anzai Mizumaru, a special pamphlet included with the essay collection Uzumaki neko no mitsukekata.

In this section, they’re talking about the types of customers at sushi restaurants:

村 客の立場から見て、寿司屋で僕がいちばん好きな客っていうと、やっぱり不倫のカップルですね。男が四十代後半から五十代、女が二十代後半っていう感じ。ひそひそっと隅っこで意味ありげな話なんかしてね。いかにも寿司屋らしくていいですよ。サマになるし。だいいち静かだし。

(オガミドリ)へへえ。

村 「これからやるんだな」ってカップルって、雰囲気でわかりますよね。

水 もちろんわかるね、ふふふ。

村 でも僕は個人的には、寿司を食ってからやるよりは、やってからゆっくり食べる方がいいですね。

水 そんなのいないよ、普通は食べてからやるもんだよ。

村 そうかなあ、僕が変なのかなあ。でもさ、やってる最中にこの女はさっきトロとあなごとウニを食ったな、なんて思い出すと感興がそがれませんか?お腹の中にそういうのが入っているのかしら、とかさ。ちょっと生臭くない?

水 そんなこと、誰も思わないよ。それにさ、終わってから寿司食べたりしたら、その方が逆に生々しいよ、ちょっと思い出したりしてさ(笑い)。それじゃブニュエルの世界だよ。

村 でもさ、終わったら腹減りませんか?

水 減らないよ。あとは寝るだけだよ。セックスしたあとで寿司食うなんて、そんな奴いないよ。村上君くらいだよ。

Mura: As a customer, my favorite sushi restaurant customers are definitely the adulterous couples. The ones where the men are in their late-40s to 50s and the women are in their late-20s. They sit in the corner and seem to be whispering conversation laden with meaning. That seems just like a sushi restaurant. So fitting. Mostly because it’s quiet.

(Ogamidori: Hehe)

Mura: You can tell the couples that are going to go do it when they leave.

Mizu: Of course you can, haha.

Mura: But personally, doing it and then taking your time to eat is better than eating sushi and then doing it.

Mizu: No one does that. Usually you eat and then do it.

Mura: You think? Maybe I’m weird. But look, doesn’t it turn you off when you realize right in the middle of doing it that this woman was just eating fatty tuna, anago, and uni? That all of that is in her stomach? It’s not a little too fishy for you?

Mizu: Nobody thinks that. And conversely it’s fishier to eat sushi after you finish, thinking about what you did (laughs). That’s like something out of Buñuel.

Mura: But don’t you get hungry when you finish?

Mizu: Nope. I just go to sleep. Nobody goes to eat sushi after having sex. Only you!

This brings to mind a lot of Murakami’s fiction. Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (in which characters have a massive dinner—not sushi—and then have sex; and in which the pleasure of taste and sex are both dulled in the End of the World), “The Second Bakery Attack” (in which a couple wakes up in the middle of the night with “an unbearable hunger”), “Nausea 1979” (in which a character becomes nauseous and is unable to keep down food for months at a time, possibly due to his many affairs with the wives of close friends).

There must be some other connections with novels, I just haven’t reviewed them recently. Sex and food are tightly linked as physical pleasures and sustenance in Murakami’s works.

So it’s funny to learn that Murakami is on team Fuck First! This is a term coined by advice columnist Dan Savage (also here, NSFW!). I have to say I’d agree with him. It makes me queasy to do anything too athletic on a full stomach, although I wouldn’t say that sushi in particular makes me feel weird. Usually it’s pretty light fare, so it might be the ideal Fuck After cuisine. Mexican food, on the other hand, is not.

(I was unable to find an image of a 不倫カップル at a sushi restaurant, but I did manage to find this interesting blog post where the writer seems to overhear a couple similar to the one described by Murakami. Worth a read.)

Thus ends Murakami Fest 2017! I’ll be out of the country for the announcement this year, although I’ll be on European time, so perhaps I’ll manage to watch somehow. If not, this will be the first time in 10 (?) years that I’ve missed the announcement live. If he ends up winning this year (unlikely since Dylan won last year), you will hear the やれやれ I emit over the Belgian lambic/French wine/British bitter/Scottish Scotch/Irish dry stout/whatever it is I happen to be drinking during the announcement as it echoes around the world.