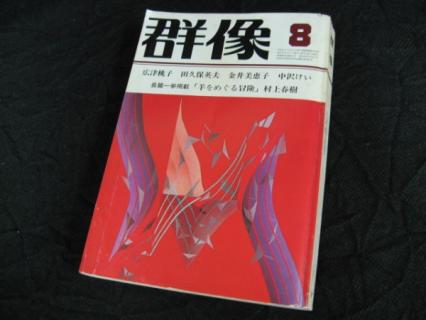

It took me long enough, but I finally finished Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World Chapter 25 “Meal, Elephant Factory, Trap,” a 31-page monstrosity during which the scientist explains exactly what he did to Watashi: install a new cognitive system (an edited version of his core identity) into his head which was used as a black box for shuffling data. Unfortunately, because his laboratory was destroyed, the scientist no longer has the ability to remove Watashi from the extra circuit he installed, which means Watashi will be stuck in that circuit (in his story called “The End of the World”) when the junction between the circuits breaks.

The chapter is a lot of pseudo-sci-fi mumbo jumbo, and I think I enjoyed it more when I first read it. The good news is that it’s more fleshed out than the “Little People” from 1Q84. And Birnbaum does some remarkable work in translation. There are minor cuts here and there as well as a few colorful renderings.

The most interesting cut comes toward the end of the chapter. Here is Birnbaum’s version:

“No, not annulled. Your existence isn’t over. You’ll enter another world.”

“Interesting distinction,” I grumbled. “Listen. I may not be much, but I’m all I’ve got. Maybe you need a magnifying glass to find my face in my high school graduation photo. Maybe I haven’t got any family or friends. Yes, yes, I know all that. But, strange as it might seem, I’m not entirely dissatisfied with this life. It could be because this split personality of mine has made a stand-up comedy routine of it all. I wouldn’t know, would I? But whatever the reason, I feel pretty much at home with what I am. I don’t want to go anywhere. I don’t want any unicorns behind fences.” (217)

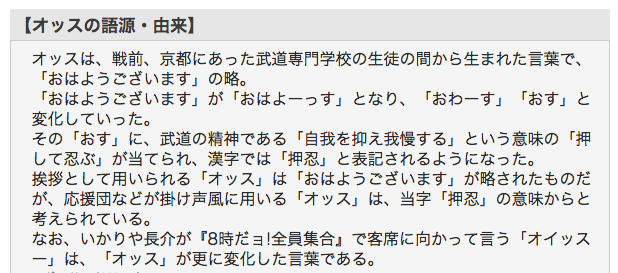

Here’s the original and my translation with the cuts highlighted in red:

「いや、あんたの存在は終わらんです。ただ別の世界に入りこんでしまうだけです」

「同じようなものですよ」と私は言った。「いいですか、僕という人間が虫めがねで見なきゃよくわからないような存在であることは自分でも承知しています。昔からそうでした。学校の卒業写真を見ても自分の顔をみつけるのにすごく時間がかかるくらいなんです。家族もいませんから、今僕が消滅したって誰も困りません。友だちもいないから、僕がいなくなっても誰も悲しまないでしょう。それはよくわかります。でも、変な話かもしれないけど、僕はこの世界にそれなりに満足してもいたんです。どうしてかはわからない。あるいは僕と僕自身がふたつに分裂してかけあい万歳みたいなことをやりながら楽しく生きてきたのかもしれない。それはわかりません。でもとにかく僕はこの世界にいた方が落ちつくんです。僕は世の中に存在する数多くのものを嫌い、そちらの方でも僕を嫌っているみたいだけど、中には気に入っているものもあるし、気に入っているものはとても気に入っているんです。向うが僕のことを気に入っているかどうかには関係なくです。僕はそういう風にして生きているんです。どこにも行きたくない。不死もいりません。年をとっていくのは辛いこともあるけれど、僕だけが年とっていくわけじゃない。みんな同じように年をとっていくんです。一角獣も塀もほしくない」 (396)

“No, you won’t stop existing. You’ll just enter into a different world.”

“It’s the same damn thing,” I said. “You know, I get it—without a magnifying glass, my existence is undetectable. It’s always been that way. It takes forever to find me in my graduation photo. I don’t have any family, so if I disappear, nobody will be hard off. I don’t have any friends, either, so no one will be sad when I’m gone. I get that. But, and this may sound strange, I was satisfied in my own way with this world. I don’t know why. Maybe I’ve been able to have some fun with everything because this split between me and my self was a nonstop comedy routine. I don’t know. But being in this world was comfortable. I hate a lot of things that exist in this world, and I think they may hate me as well, but there are some things I like, and the things I like I really like. Independent of whether or not they like me back. That’s how I live. I don’t want to go anywhere. I don’t need immortality. Getting older is tough sometimes, but it’s not like I’m the only one. Everyone gets older in the same way. I don’t want unicorns or fences.”

Not a massive cut. I wonder what these “things” are. Critics might say they’re the lifestyle choices that Murakami includes in a lot of his fiction, which makes the joke on Watashi…he still hasn’t gotten over having his apartment smashed up by the goons. A more generous reading might call them cultural objects, or art. They don’t feel quite like people.

There’s one other passage worth mentioning at the end of the chapter. There are no cuts, but Birnbaum does drop an F-bomb to show Watashi’s anger. Very interesting translation choice. And as Watashi finally blows his cool, this section also feels like an “Oscar moment” that might win an actor the award or at least a nomination. Here is Birnbaum’s translation:

“As far as I can see, the responsibility for all this is one hundred percent yours. You started it, you developed it, you dragged me into it. Wiring quack circuitry into people’s heads, faking request forms to get me to do your phony shuffling job, making me cross the System, putting the Semiotecs on my tail, luring me down into this hell hole and now you’re snuffing my world! This is worse than a horror movie! Who the fuck do you think you are? I don’t care what you think. Get me back the way I was.” (274)

And the original Japanese:

「だいたいこのことの責任は百パーセントあななにあります。僕には何の責任もない。あなたが始めて、あなたが拡げて、あなたが僕を巻きこんだんだ。人の頭に勝手な回路を組みこみ、偽の依頼書を作って僕に車夫リングをさせ、『組織』を裏切らせ、記号士に追いまわさせ、わけのわからない地底につれこみ、そして今僕の世界を終わらせようとしている。こんなひどい話は聞いたことがない。そう思いませんか?とにかくもとに戻してください」 (397)

As you can see, the “Who the fuck do you think you are?” corresponds to そう思いませんか (“Wouldn’t you agree?”) in Japanese. A pretty dramatic shift in tone there, and not undeserved. Birnbaum gives Watashi a bit more fire and brimstone here.

This is especially notable (and funny) because earlier in the chapter, (in a section that was heavily adjust by Birnbaum [or his editor]) there is an exchange of dialogue where the scientist hesitates to tell Watashi the truth because he is afraid Watashi will get angry. Watashi then says he won’t get angry…a promise he breaks here at the end of the chapter.