I was in the Japan Times this week with a curated look at Aozora Bunko, a great source for public domain literature in Japanese: “Blue Sky Books is a literary treasure trove.”

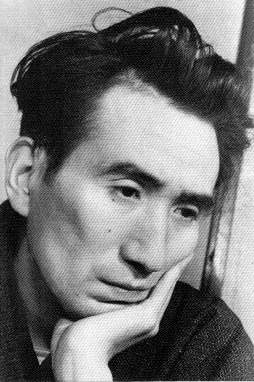

My encounters with Dazai Osamu on Aozora Bunko have been revelatory. I’d only ever read him in translation previously, and nothing ever really struck me (for which I’ll blame youthful ignorance), but I remember a friend at Waseda saying that she loved his sentences, and I can now say that I know what she was talking about.

To try to give you a good example of this, I’ve translated one of his shorter nonfiction pieces on Aozora titled 東京だより (Tokyo dayori, Dispatch from Tokyo). I don’t think I do him full justice, but it was a fun exercise:

Dispatch From Tokyo

Dazai Osamu

Tokyo is currently full of working girls. Morning and evening, on their way to and from the factories, the girls march through the streets of Tokyo in double-file columns singing the songs of industrial soldiers. They wear almost exactly the same clothing as boys. However, the straps of their geta are red, and this lone point leaves them with an aura of femininity. All of the girls have the same look on their faces. You can’t even tell clearly how old they are. When offered up to the Emperor, perhaps all humans are cleanly stripped of all facial features and age. This isn’t only when they march through the streets of Tokyo; when I see these girls laboring or working, each of their features lost and their so called “personal circumstances” also forgotten, it’s even easier for me to understand that they’re exerting themselves for their country.

Just the other day, a friend of mine who is an artist was drafted to work at a factory, and I had to see him about something, so I visited the factory three times. This something was that he is going to draw the cover for one of my fiction collections that should be published soon, but in truth I always make fun of his works, and in the past he asked several times to draw the cover of my collection, but I rejected him outright and said, if I let you draw the cover, even one of my books that wasn’t considered any good to begin with would get even worse and would never sell a single copy, so, yeah, I’ll pass. Actually, his drawings were really bad. But he got in touch with an incredibly solemn request and said he was going into the factory and now was precisely the moment to try to draw the cover for my collection with a fresh mindset, so I quickly set out for the factory to ask him to draw the cover. I didn’t care if it was crap. I didn’t care if the collection was reviewed poorly. None of those things mattered. If drawing the cover for my boring collection lifted his spirits at the factory, then nothing would make me happier. I received his touching correspondence and quickly set out for the factory where he works. He greeted me with great joy and told me about his various plans for the cover. Each and every one was unsatisfactory. It shocked me how cliched and sentimental they were, but, yet, given the situation, the quality of the drawing was not the problem. My next collection might be ruined due to his drawing, but, nevertheless, I couldn’t have cared less about it. Didn’t someone once say, do unto others? He excitedly told me about his boring ideas and then the next time he showed me even more boring drafts of the drawings, so I was frequently summoned and had to go to his factory.

I passed through the gate of the factory, showed the guard the letter from him, and entered the administrative office, where ten girls were quietly attending to administrative duties. I told one of the girls the reason for my visit and had her phone his guard room. He slept in one room of the factory, so he had made sure to inform me of his break times in his letter, and I was able to make a short visit during those break times. Until he got to the office, I sat in a small chair in one corner and stared off into space as I waited, but actually I wasn’t that spaced out. I was surreptitiously observing the ten girls who were working right in front of me. They had already, in almost beautiful fashion, cooly ignored my presence. I’ve been accustomed to being ignored by girls since my childhood, so I wasn’t particularly surprised, but the way they ignored me showed no trace of arrogance; they all simply looked downward and diligently attended to their duties without a shift in attitude revealed on any of their faces, and there was no sign of any change in the quiet atmosphere due to the coming and going of visitors—it was an incredibly pleasant scene; I could hear only the crisp sounds of the abacus and the turning of pages in the ledgers. There weren’t noticeable expressions on any of the girls faces, which made them seem like identically colored butterflies quietly lined up on the branch of a flower, but there was one who, for some reason, had an unforgettable impression. This is a rare phenomenon when it comes to working girls. I stated previously that there weren’t even slight distinguishing features between each of the working girls, but there was the one in the administrative office of that factory who had a completely different sense from the other girls. There was nothing all that different about her face. It was longish and tan. There was nothing different about her clothes either. She was wearing the same black work uniform as everyone. There was nothing different about her hairstyle either. There was nothing different about anything about her. Nevertheless, she was beautiful and vividly different from the others, as though a green butterfly was mixed in amongst black swallowtail butterflies. Yes. She was beautiful. She wasn’t wearing any makeup. Still, she was completely different and beautiful. I couldn’t help but be intrigued. I must confess that while I waited for the artist in that office, I was looking only at that mysterious girl’s face. I settled myself down and came to the most plausible conclusion that it was her bloodlines. Her father or mother had noble blood for many generations in the distant past, therefore she gave off this strange scent despite having no discernible features. I sat alone intrigued and sighed thinking of how important bloodlines are for humans, but I was wrong. My lone conclusion was completely off. The reason she was so prominently, mysteriously beautiful lay within a solemn—even sublime—urgent reality. One evening, when I was leaving through the front gate of the factory after completing my third visit, I happened to hear the girls singing behind me and turned around to see them come out from the factory courtyard in double-file lines, loudly singing the songs of industrial warriors. I stopped to watch the energetic group go by. And then I was astonished. The girl from the office came walking with crutches, slightly behind everyone else. As I watched, my eyes began to burn. The girl who should’ve been beautiful, her legs were deformed from birth. Her right leg right around her ankle—no, I can’t bring myself to say it. She passed by me silently on the crutches.

The piece is striking for its variety of sentences. Dazai has total control and jumps back and forth between shorter and longer phrases. There is some repetition of terminology (such as 事務所), but I think they can be chalked up to linguistic differences.

I wasn’t quite sure what to make of 男子意気に感ぜざれば. I found a few instances of 人生意気に感ず, which has a few good explanations here and here, so I made up something that seems to fit. Let me know if you see any other blatant mistakes.

Dazai has a long list of shorter pieces on Aozora that are manageable reads in addition to longer works like 人間失格 (Ningen shikkaku, No Longer Human). There are also a number that are related to the war, which are interesting…I don’t think I’d read many primary texts about the war experience in Japan. I think this piece can be read as a subtle critique of the war effort and its effect on the populace.