Now begins the Sixth Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement.

For those of you who don’t know how this works, check out the past five years:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

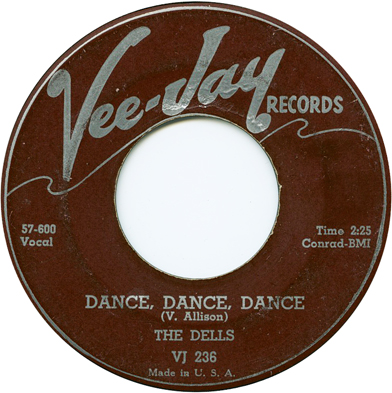

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

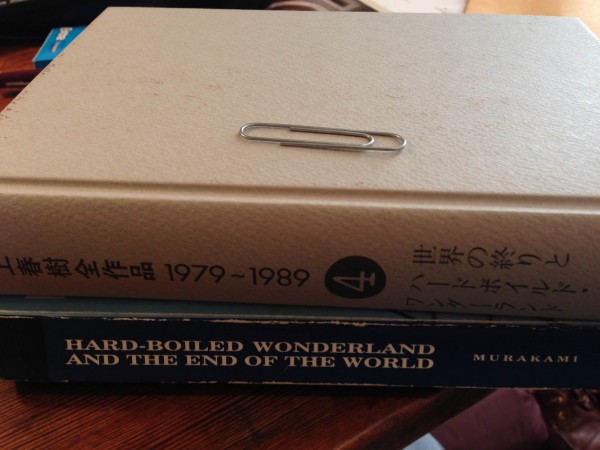

This year I’ll be even lazier than normal and just continue my close comparison of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World with its translation. I’ll be looking at a chapter a week.

This week I’m looking at Chapter 7, which is in the Hard-boiled Wonderland section of the novel. Watashi gets home from his job laundering the data, has a sleep, and gets up the next day to do some shopping and consider his new gift from the old man: a unicorn skull (but he doesn’t know that yet). He checks out some books at the library, hits on the librarian, and then has her bring him books on unicorns after it’s clear that Semiotecs are scoping out his apartment and trying to get the skull.

I am a changed man after reading this chapter.

Why? you may ask. It is because, for the first time in my history of reading Murakami (14 years, now), I have DEFINITIVE PROOF that Murakami makes edits to his manuscripts for the Complete Works editions.

But first, let’s look at the translation. Birnbaum is up to his usual techniques in this chapter:

– He compresses where Murakami sometimes goes long. When Watashi returns from shopping, he details how he puts away all his groceries – wrap the fish and meat, put the coffee and bread in the freezer, put the beer in the fridge, throw out the old veggies, hang the clothes, etc. Birnbaum renders this “Back at the apartment, I put away all the groceries. I hung my clothes in the wardrobe” (76). Capiche?

[Here’s how Rubin translates that section, which is very close to the original Japanese:

Back in my room, I put the groceries away in the refrigerator, tightly wrapping the meat and fish in plastic and freezing some for later. I froze the bread and the coffee beans, too. The block of tofu I floated in a bowl of water. The beer went into the refrigerator along with the vegetables, though I took care to keep the older vegetables closer to the front. I hung my clothes in the wardrobe and lined up the soaps and detergents on the kitchen shelf. (77)

]

– He cuts possibly unnecessary culture drops. Wilhelm Furtwängler anyone?

[Rubin’s translation of the line that was cut:

In contrast to the skull, the rod was heavy and had the same kind of intimidating quality as the ivory baton that Furtwängler had used to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic. (71)

]

– He translates a little more cleverly than Murakami’s Japanese. For example, this passage:

ペーパー・クリップなんてどこにでもある。千円だせば一生使うぶんくらいのペーパー・クリップが買える。私は文房具屋に寄って千円ぶんのペーパー・クリップを買った。(110)

Birnbaum renders this:

Paperclips were indeed used by everyone. A thousand yen will buy you a lifetime supply. Sure, why not. I stopped into a stationery shop and bought myself a lifetime supply. (76)

It’s a neat translation but not precise with the 千円ぶん. He uses the transitive property to translate that as “lifetime supply” rather than “a thousand-yen worth.”

[ Rubin’s translation:

Paper clips were everywhere. For a thousand yen, you could buy a lifetime supply. I stopped by a stationer’s and bought a thousand yen’s worth of paper clips. Then I went home. (77)

]

– He cleans up the end of the chapter. Rather than end with a short declarative statement by Watashi (私は喜んで道順を教えた; I gladly told her the way to my place), he ends it on a line of dialogue by the librarian: “I don’t know why I’m doing this,” she said, “but I don’t suppose you’d want to tell me the way to your place” (82). The translation is cleaner and much more suggestive. [Rubin ends the chapter like this: “Well, then, she said, “are you going to tell me the way to your place or not?” I happily told her the way.”]

This is Birnbaum being Birnbaum. This is why we love him.

I was prepared to write a very different entry because I found what I thought was a very large addition by Birnbaum to the manuscript. On page 73, after Watashi eats lunch at a restaurant, he drinks his post-meal coffee and thinks about the fat granddaughter, then about the last time he slept with a fat girl. I’ll give the section in its entirety here because it’s great:

The last time I’d slept with a fat female was the year of the Japanese Red Army shoot-out in Karuizawa. The woman had extraordinary thighs and hips. She was a bank teller who had always exchanged pleasantries with me over the counter. I knew her from the midriff up. We became friendly, went out for a drink once, and ended up sleeping together. Not until we were in bed did I notice that the lower half of her body was so demographically disproportionate. It was because she played table tennis all through school, she had me know, though I didn’t quite grasp the causal relationship. I didn’t know table tennis led to below-the-belt corporeality.

Still, her plumpness was charming. Resting an ear on her hip was like lying in a meadow on an idyllic spring afternoon, her thighs as soft as freshly aired futon, the rolling flow of her curves leading gracefully to her pubis. When I complimented her on her qualities, though, all she said was, “Oh yeah?” (73)

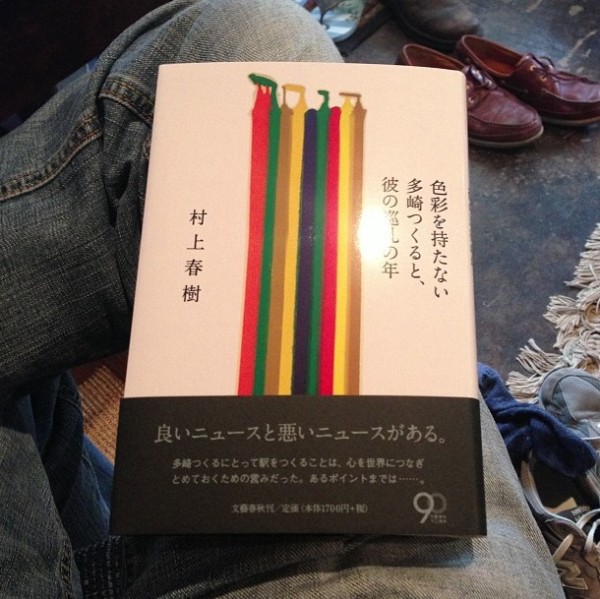

This passage is nowhere to be found in the Complete Works edition. I was prepared to discuss how this might have been an attempt by Birnbaum to give the book a little more fleshed out (excuse the pun) back story (excuse the pun) and connect it with a Japanese historical timeline. But just to be safe, I decided to pull out my paperback and hardback copies of the book (yes, I have, like, five copies of this book; it’s a sickness).

And there it was. The passage is complete in both of the pre-Complete Works versions. Birnbaum makes a few minor adjustments, but it’s nothing out of the ordinary. All within his standard operating procedures. After this paragraph, however, Birnbaum does cut two smaller paragraphs that go on longer about sleeping with fat females.

For what it’s worth, here are those two extra paragraphs in Japanese:

もちろん全体がむらなく太った女と寝たこともある。全身が筋肉というがっしりした女とも寝たことがある。はじめの方はエレクトーンの教師で、あとの方はフリーのスタイリストだった。そんな風に太り方にもいろんな特徴があるのだ。

このようにたくさんの数の女と寝れば寝るほど、人間はどうも学術的になっていく傾向があるみたいだ。性交自体の喜びはそれにつれて少しずつ減退していく。性欲そのものにはもちろん学術性はない。しかし性欲がしかるべき水路をたどるとそこに性交という滝が生じ、その結果としてある類の学術性をたたえた滝つぼへと辿りつくのだ。そしてそのうちに、ちょうどパブロフの犬みたいに、性欲から直接滝つぼへという意識回路が生まれることになる。でもそれは結局、私が年をとりつつあるというだけのことなのかもしれない。

Here’s my translation:

I did also sleep with a fat woman whose body was more evenly distributed. And with a woman who was a total beefcake – muscles all over. The former taught electric organ, and the latter was a freelance stylist. So even being fat has its own little quirks.

The more women you sleep with, the more scientific you end up being about the whole thing. The pleasure of the act of intercourse itself starts to fade away. Of course there’s no science in sexual desire. However, when sexual desire follows its appropriate course, it produces the waterfall of sexual intercourse, and as a result, it does lead to a pool filled by a sort of science. And soon enough, just like Pavlov’s dog, it creates a consciousness circuit that leads directly to that pool. Or maybe it’s just that I’m getting old.

[These sections are entirely cut from Rubin’s translation because they only exist in the original version of the novel.]

I’m not sure if I’m following Watashi’s thought process here, but that might be the point: maybe he’s supposed to sound like a guy who’s tired and confused, drinking a cup of coffee and thinking about women he slept with, possibly whom he had feelings for…or not.

The passage is more important than I initially suspected. I understand why Birnbaum cut it – Murakami does sound a bit rambly, as is his tendency – but it’s got the consciousness circuit and the waterfalls! As we all know (SPOILER ALERT!), Watashi will fall into an endless consciousness circuit because of his shuffling. And the book is heavy with waterfalls. There were waterfalls in Chapter 1 (Watashi thinks about Houdini going over Niagara Falls while trapped in the elevator), the waterfall covering the old man’s lab, and the sound of the Pool in the End of the World (which he notes is different from a waterfall). Not hugely important in terms of the overall book, but consistent enough to be called imagery and thematically significant.

Which makes me wonder why Murakami cut it in the Collected Edition. Did he think he sounded lazy or imprecise? Or did he cut the two other women because they aren’t as well developed characters, which then required the cutting of the other paragraphs?

Perhaps seeing Birnbaum’s cut in translation convinced Murakami to trim the entire section in the Collected Works manuscript? Or maybe he felt the reference to the Asama-Sansō incident was out of place when he compiled his Collected Works in the the early 90s. We may never know unless the Paris Review lets me interview the man.

[Rubin’s translations added on 2025.09.07.]