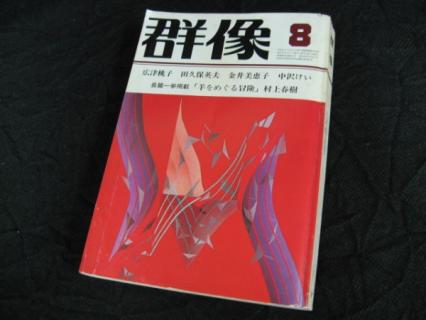

I read Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World Chapter 30 “Hole” at least a month ago (perhaps even more…I can’t remember if I read it before or after I went to Japan in March) but didn’t write up a post about it, so I’m only now going through it again and trying to figure out my impressions.

Fortunately it’s a short End of the World chapter. Boku awakes in his room and the old men are shoveling outside, digging a hole purely to dig a hole, according to the Colonel. The Colonel tells Boku that his shadow is dying and that he should go visit, and Boku resolves to do so. It’s just a small chapter to move things along.

Birnbaum (or his editor) make a number of minor cuts here and there, compress a few passages, and rearrange small pieces of the text. I guess the biggest change is the treatment of the musical instrument. In the English translation, Birnbaum has Boku discover the name of the instrument:

The room is now warm. I sit at the table with the musical instrument in hand, slowly working the bellows. The leather folds are stiff, but not unmanageable; the keys are discolored. When was the last time anyone touched it? By what route had the heirloom traveled, through how many hands? It is a mystery to me.

I inspect the bellows box with care. It is a jewel. There is such precision in it. So very small, it compresses to fit into a pocket, yet seems to sacrifice no mechanical details.

The shellac on the wooden boards at either end has not flaked. They bear a filligreed decoration, the intricate green arabesques well preserved. I wipe the dust with my fingers and read the letters A-C-C-O-R-D-…

This is an accordion!

I work it, in and out, over and over again, learning the feel of it. The buttons vie for space on the miniature instrument. More suited to a child’s or woman’s hand, the accordion is exceedingly difficult for a grown man to finger. And then one is supposed to work the bellows in rhythm. (314-315)

Birnbaum did this in the previous chapter as well, but as you can see above it’s a bit more blatant. In the Japanese original, Murakami uses a complex kanji compound for accordion (手風琴) the entire time. He does switch to the katakana version of the word (アコーディオン) in this passage, but the effect is not the same. Here is the Japanese and my translation:

部屋があたたまると僕は椅子に腰を下ろしてテーブルの上の手風琴を手にとり、蛇腹をゆっくりと伸縮させてみた。自分の部屋に持ちかえって眺めてみると、それは最初に森で見たときの印象よりずっと精巧にしあげられていることがわかった。キイや蛇腹はすっかり古ぼけた色に変わっていたが、木のパネルに塗られた塗料は一カ所としてはげた部分がなく、緑に描かれた精緻な唐草模様も損なわれることなく残っていた。楽器というよりは美術工芸品として十分に通用しそうだった。蛇腹の動きはさすがにいくぶんこわばってぎこちなかったが、それでも使用にさしつかえるというほどではなかった。おそらくそれはかなり長いあいだ人の手に触れられることもなく放置されていたのに違いない。しかしそれがかつてどのような人の手によって奏され、そしてどのような経路を経てあの場所まで辿りつくことになったのかは僕にはわからなかった。すべては謎に包まれていた。

装飾の面だけではなく、楽器の機能性をとってみてもその手風琴はかなり凝ったものだった。だいいちに小さい。折り畳むとコートのポケットにすっぽりと入ってしまう。しかしだからといって、そのために楽器の機能が犠牲になっているわけではなく、手風琴が備えているべきものはそこには全部きちんと揃っていた。老人たちが穴を掘りつづける音はまだつづいていた。彼らの四本のシャベルの先が土を噛む音が、とりとめのない不揃いなリズムとなって妙にはっきりと部屋の中に入りこんできていた。風が時折窓を揺らせた。窓の外にはところどころに雪が残った丘の斜面が見えた。手風琴の昔が老人たちの耳に届いているのかどうか、僕にはわからなかった。たぶん届きはしないだろう、と僕は思った。音も小さいし、風向きも逆になっている。

僕がアコーディオンを弾いたのはずいぶん昔のことだったし、それもキイボード式の新しい型のものだったから、その旧式の仕組とボタンの配列になれるにはかなりの手間がかかった。小型にまとめられているせいで、ボタンは小さく、おまけにひとつひとつがひどく接近していたから、子供や女性ならいざしらず手の大きな大人の男がそれを思うように弾きこなすのはかなり厄介な作業だった。そのうえにリズムをとりながら効果的に蛇腹を伸縮させなくてはならないのだ。 (456-457)

Once the room warms, I sit in a chair at the table, take the accordion in my hands, and slowly move the bellows in and out. Now that I’ve brought the instrument to my room and have a chance to look at it, I understand that that it is much more elaborately finished than I thought from my initial impression in the forest. The keys and bellows have colored with age, but the paint on the wood panels has not flaked at all, and the delicate arabesques painted in green remain unharmed. It could pass as a work of decorative art more than an instrument. The bellows have predictably stiffened somewhat and are awkward, but it isn’t enough to impede its usage. It must have been left untouched for quite a long time. However I don’t know what kind of people played it long ago nor how it made its way to that place. It’s wrapped in mysteries.

The instrument’s functionality, in addition to its decoration, is also quite refined. Most importantly, it’s small. Folded up, it could fit cleanly into a coat pocket. Which isn’t to say that that any functionality has been sacrificed; everything you would expect an accordion to have is there.

The sound of the old men digging the hole continues. The noise of four shovel tips biting into the earth turns into a ceaseless, irregular rhythm and echoes with a strange clarity throughout the room. The wind rattles the window every now and then. Outside the window I can see the slope of the hill, covered here and there with snow. I can’t tell whether the sound of the accordion reaches the old men. I imagine it doesn’t. The accordion is quiet, and the wind blows in the opposite direction.

It’s been a long time since I played the accordion, and it was one with a newer style of keyboard, so it takes some effort to get accustomed to the way the old style works and the layout of the buttons. The buttons are small because they’re fit into the compact form, and what’s more they’re extremely close together; I’m not sure about women and children, but it’s incredibly difficult work for a grown man with large hands to have a command of the instrument as he would like. And on top of that I have to make sure to move the bellows in rhythm.

As you can see, BOHE has compressed a good portion of the text, rearranged, and added his own creative touches. It covers most of the bases and the result is a very creative translation. He even treats the simplest sentences with total respect; I’m thinking in particular of “The buttons vie for space on the miniature instrument.” That strikes me as a very generous way to render Murakami in English without going over the line, as perhaps some of the other choices do.

Also notable in this chapter is the appearance of more lines from Dead Heat on a Merry-go-round! Here’s the passage in English:

“They dig holes from time to time,” the Colonel explains. “It is probably for them what chess is for me. It has no special meaning, does not transport them anywhere. All of us dig at our own pure holes. We have nothing to achieve by our activities, nowhere to get to. Is there not something marvelous about this? We hurt no one and no one gets hurt. No victory, no defeat.” (317)

And here is the Japanese followed by a rewritten version of Birnbaum’s translation with the deleted sections added in:

「彼らはときどき穴を掘るんだ」と老人は言った。「たぶん私がチェスに凝るのと原理的には同じようなものだろう。意味もないし、どこにも辿りつかない。しかしそんなことはどうでもいいのさ。誰も意味なんて必要としないし、どこかに辿りつきたいと思っているわけではないからね。我々はここでみんなそれぞれに純粋な穴を掘りつづけているんだ。目的のない行為、進歩のない努力、どこにも辿りつかない歩行、素晴らしいと思わんかね。誰も傷つかないし、誰も傷つけない。誰も追い越さないし、誰にも追い抜かれない。勝利もなく、敗北もない。」

“They dig holes from time to time,” the Colonel explains. “It is probably for them what chess is for me, in principle. It has no special meaning, does not transport them anywhere. But that doesn’t matter. No one needs meaning, and no one wants to be transported anywhere. All of us dig at our own pure holes. We have nothing to achieve by our activities, no progress to accomplish with our effort, nowhere to get to. Is there not something marvelous about this? We hurt no one and no one gets hurt. We overtake no one, and no one is overtaken. No victory, no defeat.” (317)

Pretty interesting. Birnbaum cuts the one sentence that really links it with Dead Heat, and that is the “overtake, overtaken” line.

We should be approaching another Dead Heat reference in the Hard-boiled Wonderland section of the novel as well. I’m looking forward to making some progress on this relatively meaningless exercise. I hope you enjoy following along as I dig my hole.