Chapter 16, “The Coming of Winter,” is another nice chapter in Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World where Murakami is beginning to set up the major connections between the two parts of the novel that will play out in the second half: “Mind” and how it affects the people in the Town.

In this chapter, Boku wakes up sick, and the Colonel cares for him. He recovers slowly, has the Colonel deliver the map concealed in a shoe to his shadow, and finally visits the Librarian again.

There are no major revisions by Murakami between versions in this chapter, but Birnbaum (or his editor) [I should really just start calling this “BOHE” to be fair to Birnbaum; translators always take the blame, but editors could be equally if not more guilty] gets up to his old tricks of cutting the final few lines at the end of a section or the chapter in order to end with strong language.

Take this section:

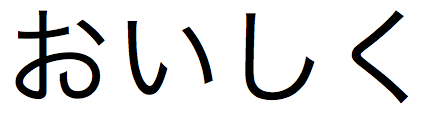

「不思議なものですね」と僕は言った。「僕はまだ心を持っていますが、それでもときどき自分の心を見失ってしまうことがあるんです。いや、見失わない時の方が少ないかもしれないな。それでもそれがいつか戻ってくるという確信のようなものがあって、その確信が僕という存在をひとつにまとめて支えているんです。だから心を失うというのがどういうことなのかうまく想像できないんです」

老人は静かに何度か肯いた。

「よく考えてみるんだね。考えるだけの時間はまだ残されている」

「考えてみます」と僕は言った。 (231-232)

“It’s strange,” I say. “I still have my mind, but occasionally I seem to lose sight of it. Actually, the times when I don’t lose sight of it are far more infrequent. But I feel confident that it will return at some point, and that confidence supports my entire existence. So it’s difficult to imagine what it would be like to lose one’s mind.”

The old man nods quietly. “Think about it long and hard. There’s plenty of time left for you to think.”

“I will,” I say.

I’m not happy with my translation of 見失う, but it’ll do for the purposes of comparison. I’ve also eliminated one of the line breaks to try and make it more clear that the Colonel is speaking. I was tempted to split his line with a dialogue tag. Here is what Birnbaum does:

“It is so strange,” I say. “I still have my mind, but there are times I lose sight of it. Or no, the times I lose sight of it are few. Yet I have confidence that it will return, and that conviction sustains me.” (170-171)

Hmm…interesting. Birnbaum [or his editor] seems to make a small error: He fails to notice the negative ending of the verb 見失う in the second usage. Which muddles the translation. Boku is trying to emphasize exactly how infrequently he is aware of the presence of his own mind.

More importantly for the purposes of this blog post, Birnbaum also cuts the final four lines (marked in red above). This is a nice strategic choice. He picks the strongest line and says BOOM, we’re done here, time to move on. His translation is wonderful: “That conviction sustains me” is a great forceful way to end. Strong, adaptive, creative translation. What do you think? Does he go to far here?

I forget whether I’ve mentioned this in previous posts, but this might be a good point to remind readers that Birnbaum uses “mind” for 心 (kokoro), which I think makes a huge difference in the translation. I feel like the repetition of “heart” would start to get saccharine at some point and become less compelling over the course of the novel. Mind, on the other hand, is worth pursuing.

Birnbaum makes other cuts at the end of the whole chapter that have greater implications for the theme and language that Murakami uses in this chapter.

Boku gets to the library and waits for the Librarian. She takes a while to arrive, and when she does, he mentions that he thought she wouldn’t come:

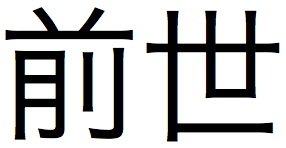

「どうしてもう来ないなんて思ったの?」と彼女は言った。

「わからない」と僕は言った。「ただそんな気がしたんだ」

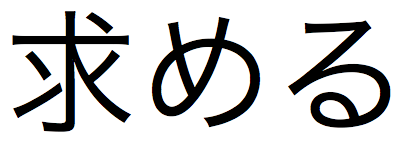

「あなたが求めている限り私はここに来るわ。あなたは私を求めているんでしょう?」

僕は肯いた。確かに僕は彼女を求めているのだ。彼女に会うことによって、僕の喪失感がどれほど深まろうと、それでもやはり僕は彼女を求めているのだ。 (235)

“Why did you think I wouldn’t come?” she asks.

“I don’t know,” I say. “I just had a feeling.”

“As long as you want me, I’ll come. You do want me here, right?”

I nod. I definitely want her. My sense of loss deepens when I see her, but despite that I want her.

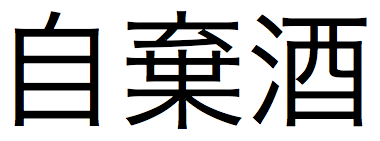

The key word we’re looking at here is 求める (もとめる), which can be “want” or “request” (unless I’m misreading it?). I rendered it once as “want me here” because I wasn’t quite bold enough to have Boku say “I want you” directly to the Librarian. As you can see in the translation, Birnbaum also avoids this through cuts and by translating 求める as “need”:

“Did you not think I would come?” she asks.

“I do not know,” I say. “It was just a feeling.”

“I will come as long as you need me.”

Surely I do need her. Even as my sense of loss deepens each time we meet, I will need her.” (173)

Birnbaum also cuts the few lines (highlighted in red) where Boku explicitly acknowledges his need/desire for her when she asks. The result is a much more implicit (dare I say “Japanese”?) conversation.

But this section is also interesting when read alongside cuts at the end of the chapter:

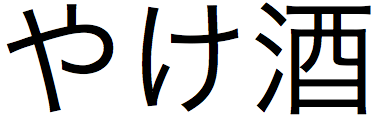

「君は君の影が戻ってきたとき彼女に会ったのかい?」

彼女は首を振った。「いいえ、会わなかったわ。私には彼女に会う理由がないような気がしたの。それはきっと私とはまるでべつのものだもの」

「でもそれは君自身だったかもしれない」

「あるいはね」と彼女は言った。「でもどちらにしても今となっては同じことよ。もう輪はとじてしまったんだもの」

ストーヴの上でポットが音を立てはじめたが、それは僕には何キロも遠くから聞こえてくる風の音のように感じられた。

「それでもまだあなたは私を求めているの?」

「求めている」と僕は答えた。 (236)

“Did you meet your shadow when she came back?”

She shakes her head. “No, I didn’t. I felt like there wasn’t any reason to meet her. I just felt like she was something totally separate from me.”

“But maybe she was part of yourself.”

“Maybe so,” she says. “But it’s all the same either way now. The circle has already closed.”

The pot on the stove starts to rattle, but it sounds like the wind miles in the distance.

“Do you still want me?”

“I do,” I say.

And here is how Birnbaum renders this scene:

“Did you meet with your shadow before she died?”

She shakes her head. “No, I did not see her. There was no reason for us to meet. She had become something apart from me.”

The pot on the stove begins to murmur, sounding to my ears like the wind in the distance. (173)

Again I’ve marked the redacted lines in red, and again you can see that Birnbaum cuts 求める. The communication between the two characters becomes far more implicit in translation than in the Japanese, which ratchets up the tension.

I don’t normally like stories/chapters/writing that begin or end with dialogue, but the original Japanese isn’t bad as far as dialogue goes. It feels decisive, especially when rendered into English where it isn’t necessary to repeat the actual verb itself. But Birnbaum’s translation also has its appeal, and it reminds me why I loved/love the novel so much and why it hit me so forcefully when I read it at 17 (15 years ago, damn): That unresolved, unspoken tension made me wonder whether Boku would be able to connect with the Librarian, and I kept turning the pages to find out.