Welcome to the Eighth Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see past entries in the series here:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits

The 自作を語る for A Wild Sheep Chase is interesting. Murakami goes into detail about how drastically he changed his life after publishing his second novel: he moved to Chiba, started taking trips abroad, stopped drinking as much, and basically stopped living the urban social life he’d been living as the owner of a jazz pub.

He wrote the book from the fall of one year to the spring of the next, a pattern that he repeated for Dance Dance Dance. He went to Hokkaido to research sheep, without any real idea of the novel in mind, and he started writing and eventually the sheep fit in to the story. He also mentions how he was driven to write by a sense of competition with Ryū Murakami following the publication of Coin Locker Babies.

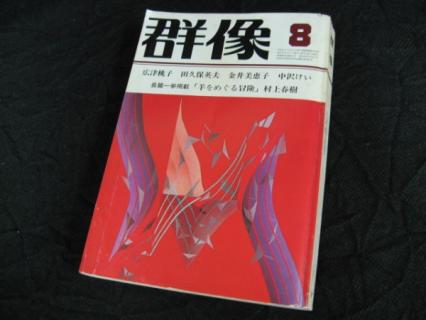

One of the things I didn’t know (or had forgotten) was that the novel was published in Gunzō. Murakami writes about that experience:

この作品は『群像』に一挙掲載のかたちで発表されたが、書いている途中で担当編集者が交代し、また編集部の方針も大きく変化したこともあって、作品はやっと出来あがったものの、作品の立場も僕の立場も正直言って—もうずいぶん昔のことだし、状況も変わったから正直に言っていいと思うのだけれど—あまり居心地がいいとは言えなかったように記憶している。なんだか出来の悪い醜い子供を産んでしまったあひるのお母さんみたいな気分だった。もちろん雑誌には雑誌のきちんとした性格なり方針なりがあるのは当然のことで、僕としてはそのこと自体はいっこうに構わないのだが、でもその時、雑誌といういれものは短編やエッセイはともかくとして、息の長い仕事をするには適していないのかもしれないという印象を持った。長編小説を書くというのは本当にデリケートな作業である。それは往々にして骨を削るような孤独な集中力を要求する。そしてちょっとした些細なことで力のバランスが狂ってしまいかねないのだ。

そのせいもあってこれ以降長編小説には全部書きおろしというシステムを取るようになった。まあ人にはいろいろな事情や仕事のやり方があるだろうけれど、経験的に言って、僕の場合は性格的に書きおろし形式が適していると思う。他の仕事は一切はずして、何ヶ月か集中して一気に書き上げ、それからゆっくり時間をかけて推敲するという書き方なので、連載小説というのはどうしてもできないし、かといって雑誌一挙掲載というのも何か二度手間みたいな気もする。そういう自分にいちばん適した書き方のペースを摑んだのもこの小説をとおしてだった。 (VI-VII)

This work was presented in Gunzō in its entirety, but the editor in charge changed while I was writing, and the editorial department’s objectives also underwent large changes, so while I finally managed to finish the novel, I do remember that its position as well as my own could not be called all that comfortable, to put it honestly—this happened long ago and the situation has changed, so I think it’s okay to put it honestly. I felt something like a mother duck who’d given birth to an ugly, misbegotten duckling. Of course it’s only natural that a magazine have its own proper, magazine-like character and objective, and I didn’t have any problem with those things themselves, but I was left with the impression that, at that time, setting aside short fiction and essays, magazines as a vehicle might not have been suited for sustained work. Writing a full-length novel is truly delicate work. It often demands a focus so lonely that it wears you down. And the slightest thing can throw off the balance of your powers entirely.

This is among the reasons I adopted the system of writing all my novels after this one as kaki-oroshi (new work published straight into book form). Well, I guess people must have various circumstances and ways of working, but speaking from experience, I believe that the form of kaki-oroshi suits me personality-wise. My writing process is to let go of all other work entirely, focus for several months and write everything up in one go, then take my time with revisions, so I’m totally unable to do serialized fiction, but having said that, I do want to have another go at publishing something in its entirety in a magazine. It was through this novel that I also came to understand this writing pace that most suits me. (VI-VII)

I wonder what it was about the new editor(s) and his/her/their new goals that irked him so much. It sounds like they wanted him to make changes to the work that he was uncomfortable with. I wonder if he was submitting excerpts and receiving feedback as he wrote. (He mentions that he wrote 650 Japanese manuscript pages, which was long for him at the time but nothing compared to his recent monstrosities.)

One final interesting thing to note is that Murakami would break this vow just a few years after writing this commentary. In October 1992, he began to serialize the first half of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle in Shinchō. This went until August 1993. The first and second half were then published in book form in April 1994.