Year Ten! Goddamn. When I began this exercise I was living in a very small room in Tokyo, working at a translation company, using Japanese every day. Today I’m sitting here in my modest Chicago apartment (cool breeze coming in off the lake through my living room windows), working during the week at a Japanese office but using the language very little. My reading group, writing for the Japan Times, and translation exercises here are my main connections to the language. Consistency matters, so we continue, even if my feelings about Murakami have shifted over the years and are as different as my living conditions then and now.

Thus, without further ado:

Welcome to the Tenth Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see past entries in the series here:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

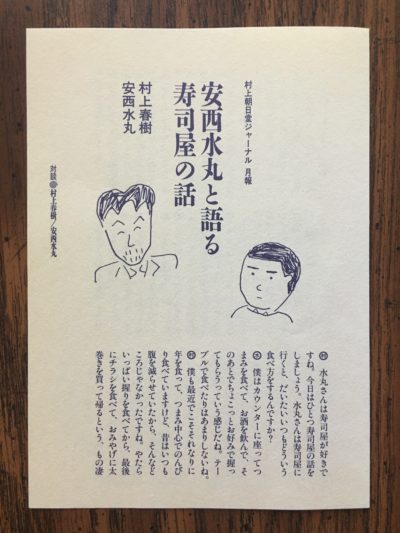

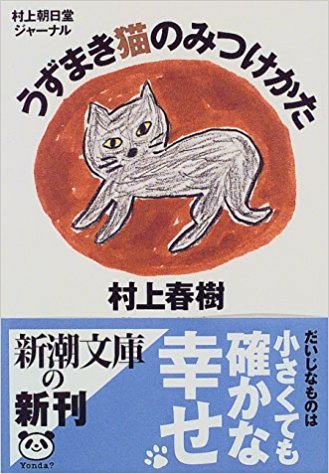

This year I’m (lazily) looking at essays from the collection 『うずまき猫のみつけかた』 (Uzumaki neko no mitsukekata, How to Find Tabby Cats). This is a spiritual successor to 『やがて哀しき外国語』 (Yagate kanashiki gaikokugo, Foreign Languages, Sad in the End [?]), which Murakami wrote while he was in Princeton. He wrote and published the essays in Uzumaki neko in the magazine SINRA from the spring of 1994 to the fall of 1995. He was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and working (I think) as a writer in residence at Tufts University.

The essays are chronological and read a lot like extended blog posts. I’m not quite sure which essay generated the title, as I haven’t read the whole collection. I’m picking out essays here and there to read, and it seems like cats figure somewhere in most of them, but never as the central character.

The first essay I’m looking at is from the summer of 1994 and is titled ダイエット、避暑地の猫 (Daietto, hishochi no neko, Diets, Summer Resort Cats). Murakami is back in Tokyo briefly, suffering from the heat, before he returns to Boston and then takes a summer trip to Vermont. Here are some passages:

今更あれこれと言い立ててどうなるというものでもないけれど、今年の日本の夏は本当に暑かった。死ぬほど暑かった。いくら用事があったとはいえ、わざわざこんな時期に日本に帰ってきて馬鹿だった。何をする気も起きなくて、しょうがないから毎日ビールばかり飲んでいた。

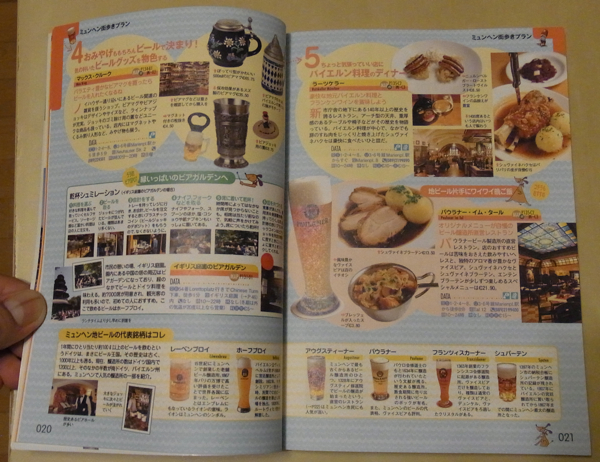

ある暑い日の午後、新宿のデパートの展示会場に永沢まことさんのトスカナの絵の個展を見にいって、そこにあった宮本『世にも美しいダイエット』美智子さんのパネルを読んでいたら、「年をとって酒を飲むのはろくなことではない」というようなことが−もちろんもっと丁寧な表現で−書いてあった。それで「確かにそうだな、僕もビールを飲むのを少し控えなくてはな」とそのときは思ったのだけれど(この人の説明にはすごく納得力がある)、一歩外に出たらもう暑くて暑くて、とにかく冷たいビールを飲むことしか考えられない。というわけで、いや、やはり飲んでますね。今年の夏は僕はおおむねキリンのラガービールを飲んでいた。とくに銘柄の好みが保守的なわけではないのだが、日本に帰ってくるたびにわけのわからない見慣れないビールが次から次へと酒屋の棚に並んでいるし、暑くてどれにしようかいちいち考えるのが面倒だったからだ。 (064)

I don’t mean to over-insist, but summer in Japan was hot. Hot enough to kill a man. I was pretty dumb to schedule a return trip to Japan during this period, even if I had things to take care of. I wasn’t motivated to do anything so I gave in and drank beer every day.

One hot afternoon, I went to see Makoto Nagasawa’s solo exhibit of Tuscany paintings at a Shinjuku department store, and I read a panel displayed there for Michiko “A Beautiful Diet” Miyamoto that read “Drinking alcohol isn’t great for you as you age,” of course expressed in much nicer language. I thought to myself at the time, “That’s true, I should cut back on the beer” (her explanation was really persuasive), but I took one step outside and it was so damn hot that all I could think about was having a cold beer. So, of course, I drank. This summer I mostly drank Kirin Lager. I’m not really a stickler about the brand I drink, but when I was back in Japan, there were so many unfamiliar beers on the shelves of liquor stores and it was so hot that trying to consider all of them was a chore.

It’s interesting to see Murakami’s take on beer. This was in 1994, right after the laws were changed to allow smaller breweries. I don’t know much about Miyamoto. It must’ve been a short-lived fad diet, although Murakami sees similarities between her and himself:

僕らのようにどこにも属していない人間は自分のことはとにかく一から十まで自分で護るしかないわけだし、そしてそのためには、それがダイエットであるにせよ、フィジカル・ワークアウトであるにせよ、自分の身体をある程度きちんと把握して、方向性を定めて自己管理して行くしかない。 (65)

People like us who don’t belong anywhere have to protect ourselves in every way, and in order to do that, you have to have a somewhat firm grasp on your body to manage yourself and determine your direction, whether it’s through a diet or through physical fitness.

There are some sections that read similar to Hard-boiled Wonderland and some of his political speeches about “individuals versus the system” and how the system generally wins.

And here’s one final passage with an unflattering look at the ladies in Vermont:

ヴァーモントには素敵なカントリー・インが数多くあって、そのような旅館を泊まり歩くのも楽しみのひとつである。まあなにしろアメリカだから、トスカナみたいに目から鱗が落ちるほど料理がおいしいとは言えないけれど、素材は新鮮だし、空気が美味くて知らず知らずお腹が減るので、ご飯は楽しく食べられる。ただし、ヴァーモントは乳製品とメイプル・シロップとが名産品なので、おいしいおいしいといって食べていると、これは確実に「世にも美しくない」ことになってしまう。実際にヴァーモントで出会った女の人の八十五パーセントまでは完全な「トド体系」であった。みんなで揃ってよくこんなに肥れるよなあと感心してしまう。腰のまわりなんか布団を巻いて歩いているんじゃないかというくらいむくむくしている。アメリカも方々をまわったけれど、こんな肥った人が多い地方も初めてである。みんなに宮本さんの本を読ませてあげたいと思ったくらいである。あって、毎日昼御飯を抜いていたのだが、それでも食事はけっこうヘビーだった。旅行するのは楽しいだけれど、トシを取ってくると、毎日外食を続けることがだんだんきつくなってくる。 (73)

There are many pleasant country inns in Vermont, and hopping around between these lodgings is also fun. It’s the United States, so the food isn’t going to blow you away like it might in Tuscany, but the ingredients are fresh, and the air is clean, and before you know it you’re hungry and can enjoy eating the meals. However, Vermont is known for dairy products and maple syrup, so while they’re delicious, you definitely end up “Not Beautiful.” About 85% of the women I actually met in Vermont were total “walruses.” I was impressed that everyone was able to get so fat. They’re so ponderous when walking around it looks like they have futon strapped to their waists. I’ve been all over the U.S., and this is the first time I’ve seen this many fat people. I wanted to make them all read Miyamoto’s book. This the case, I went without lunch every day, but even so the food was fairly heavy. Traveling is fun, but it gets harder and harder to eat out repeatedly as you get older.

Ha. What gives with the body shaming, Murakami? Maybe we can chalk this up to a 1990s lack of political correctness? Murakami doesn’t seem to realize that not everyone can/could just up and run a marathon like he does/did. Or maybe he does and attributes his fitness to a strength of character, which borders on paranoia at times. “This is what I do to maintain my independent sense of self, to maintain my direction and focus.” If there’s a weakness to this system of beliefs, I think it’s a tendency to see oneself (or the system) as flawless. I think most artists need a good portion of this attitude in order to complete any project, but too much of it can perhaps lead to an inability to self-correct…which is maybe what we’ve seen recently with Murakami.

This collection, on the other hand, seems to be one of those side projects that Murakami takes on between larger fiction projects. It’s necessarily more casual than his other work. We’ll see more next week!