Chapter 29 has some clear changes right from the beginning: The chapter title in the Complete Works edition is “Lake, Pantyhose” while in English translation and in the original paperback it is “Lake, Masatomi Kondo, Pantyhose.”

In this chapter, Watashi and the granddaughter swim across the lake, make their way through the subterranean INKling cave, and eventually get to the subway tunnels. This sounds like it could be a very short chapter, but this is Murakami we’re talking about, so we experience it through Watashi’s thoughts, which become ever more distracted as he descends into the End of the World.

Watashi thinks again of the woman wearing bracelets in the Skyline, and he turns the whole thing into an invented movie scene. The translation is really exceptional around this point, pages 305-306 in the English edition. When the granddaughter asks him what he’s thinking about, Murakami name drops some actors, which he cuts from the Complete Works edition. They remain in the English translation and look like this:

“What were you thinking about?”

“Movie people. Masatomi Kondo and Ryoko Nakano and Tsutomu Yamazaki.” (307)

This is the only place where the names are dropped in the chapter, so it’s not surprising it gets cut…unless they pop up somewhere in later chapters.

I had trouble finding Masatomi Kondo until I checked the Japanese version and realized that Birnbaum had mistaken Masaomi for Masatomi. Pretty funny mistake—shows you how important Google is. I’ve been meaning to write something about the new translations of Murakami’s first two novels because Birnbaum has a similar issue there—he makes mistakes with the names of books and movies, likely because they would have been difficult to track down back in the late 80s and early 90s without the Internet.

At any rate, here is Masaomi Kondo in some commercials that might have aired around this time. The car isn’t a Skyline, but I think this is almost exactly what Murakami was imagining. Some great shots of Kyoto back in the day as well in one of the CMs:

https://youtu.be/QcDo7sLMLAE

And there are no mistakes with Ryoko Nakano and Tsutomu Yamazaki, well known (at least abroad) for his work in Itami Juzo’s legendary Tampopo.

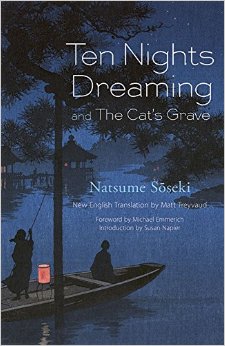

Birnbaum makes liberal cuts throughout the rest of the chapter as well, especially in a section where Watashi spends half a page trying to remember the last time he took a piss (gripping literature). This section is notable, however, for the first appearance of the “merry-go-round” image, which he would go on to use in the collection of stories Dead Heat on a Merry-go-round. Nice little easter egg for extreme Harukists.

One of the most interesting translation techniques is with the following section. The granddaughter is explaining to Watashi about how corrupt the System is, about how the Factory and System are controlled by the same forces to play each off the other for profit. Here is the Japanese original and my translation, in which the granddaughter explains the whole thing in a long piece of dialogue:

「祖父は『組織』の中で研究を進めているうちにそのことに気づいたのよ。結局のところ『組織』は国家をまきこんだ私企業にすぎないのよ。私企業の目的は営利の追求よ。営利の追求のためにははんだってやるわ。『組織』は情報所有権の保護を表向きの看板にしているけれど、そんなのは口先だけのことよ。祖父はもし自分がこのまま研究をつづけたら事態はもっとひどいことになるだろうと予測したの。脳を好き放題に改造し改変する技術がどんどん進んでいったら、世界の状況や人間存在はむちゃくちゃになってしまうだろうってね。そこには抑制と歯止めがなくちゃいけないのよ。でも『組織』にも『工場』にもそれはないわ。だから祖父はプロジェクトを降りたの。あなたや他の計算士の人たちには気の毒だけど、それ以上研究を進めるわけにはいかなかったのよ。そうすれば先に行ってもっと沢山の犠牲者が出すはずよ」

“Grandfather realized that as he continued his research at the System. In the end, the System is nothing more than a private corporation that had enveloped the state. The goal of a private corporation is the pursuit of profit. And they’ll do anything to get those profits. The System advertised itself as a protector of informational property rights, but it’s just lip service. Grandfather guessed that if he continued his research, things would only get worse. He said that the state of the world and human existence would would go to crap if the technology to modify and change the brain however you wanted was continued to develop. Controls and restraints were critical, but there were none—not in the System or the Factory. So he left the project. This was too bad for you and other Calcutecs, but he couldn’t allow the research to continue any longer. If he had, there would have been even heavier consequences.” (432)

Birnbaum takes the second half of this dialogue (right when readers would start to get bored) and turns it into Watashi’s thoughts. He cuts here and there and embellishes a little toward the end to get the character in there, but I think it’s effective. Very interesting technique:

“That’s what struck Grandfather while he was in the System. After all, the System is really just private enterprise that enlisted state interests. And private enterprise is always after profit. Grandfather realized that if he went ahead with his research, he’d only make things worse.”

So the System hangs out a sign: In Business to Protect Information. But it’s all a front. If the old man hands over technologies to reconfigure the brain, he seals the fate of humanity. To save the world, he steps down. Too bad about the defunct Calcutecs—and me, who gets stuck in the End of the World. (300)