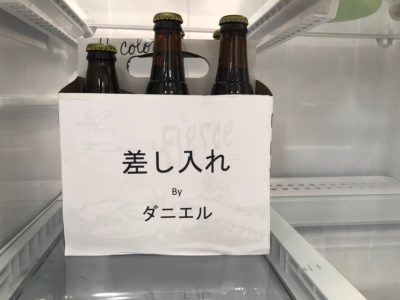

Monday night in Kanda, May 2018. Apropos of nothing other than that I, too, am a hardworking person.

I only vaguely remember my first electronic dictionary. I know I had a very small one I bought in Akihabara in 2003 that deftly jumped around between kanji and compounds. But I left it in a classroom when I got back to the states and someone took it. I’d written my name on it, I think, but it smeared a little.

I bought a new one on Amazon Japan first thing when I moved into my JET apartment, but it was bigger and bulkier and didn’t do the same tasks, despite being the same brand. Should’ve stuck with old reliable.

This was 2005, and I didn’t end up using the dictionary all that much. I switched over to the Nintendo DS kanji dictionary, which made it a breeze to draw out kanji I didn’t recognize. Since I got a smartphone in 2012, I haven’t even used that all that much.

Some of my reading I do either “skimming,” without looking up each word, and the rest (which I’m likely doing for JT articles or translation work), I’m right next to the computer and have the internet at my fingertips.

Part of the reason I can find these characters is Jim Breen. I was in the Japan Times late last month with a profile of him and a look at his WWWJDIC and underlying EDICT dictionary files: “At 180,000 entries, Jim Breen’s freeware Japanese dictionary is still growing.”

Jisho.org has been my favorite EDICT-based resource. I know that WWWJDIC has the mult-radical method as well, and maybe I should give the website another chance, but I just find Jisho so easy to use and well designed.

It’s also not often that I have to look up characters. I’m working on a big translation project that I hope to share soon, and I’m reading the text through Kindle on my iPhone, which I’ve written about previously.

I do have major complaints with the dictionary feature. Unlike Jisho, you have to hit the exact word or else it won’t return any hits. Which basically means you can’t search for conjugated verbs or adjectives or you have to hope that the individual kanji has a separate meaning/reading that will then enable you to find it with other stuff.

And my most major complaint with the Kindle is the limit on your ability to copy and paste text. I mean, I get it. You don’t want people copying and pasting the entire text, but it was so damn easy to copy from the iPhone and then paste on my desktop through the MacOS/iOS integration. There must be a way to allow copying and pasting single phrases/words with no limit. We have software smart enough to do this.

So my basic translation desktop setup is this:

– Kenkyushu Green Goddess (5th edition) app open on my iPhone (for deep dives into usages and meanings that aren’t easily summarized in a few words)

And the following browser tabs, in no particular order:

– http://jisho.org (for basic word look up)

– http://www.alc.co.jp (for usage and context clues)

– http://thesaurus.com (to give a tired English brain some alternatives or inspiration)

– https://ejje.weblio.jp/ (for more diverse and at times reliable context and usage clues)

– https://kotobank.jp/ (for Japanese definitions in order to more fully understand a word)

What am I missing? I feel like there must be an easier way to look up individual kanji. Any suggestions?