Welcome to the Tenth Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see past entries in the series here:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters

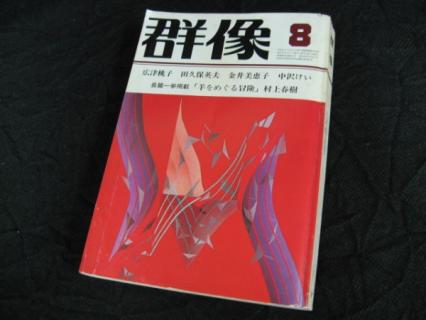

We’re continuing on with Murakami’s essay collection Uzumaki neko no mitsukekata. This week I’m looking at 「小説を書いていること、スカッシュを始めたこと、またヴァーモントに行ったこと」 (Shōsetsu o kaite iru koto, sukasshu o hajimeta koto, mata Vaamonto ni itta koto, Writing a novel, starting squash, going to Vermont again), a very short essay.

The title basically says it all. Murakami gives another long account of his daily writing routine (go to bed at 9pm, wake up at 5am to write, exercise, have lunch, and then take the afternoon to run errands, relax, or work on other writing projects), talks about how he’s taken up squash, and then visits Vermont with a friend (and talks about the Japanese association of Vermont with curry).

Murakami gives a pretty interesting account of living and writing abroad and notes where he wrote his past novels:

しかし日々こういう内向的な生活を送っていると、正直なところ、自分が外国に住んでいるという実感があまり湧いてこない。いうまでもなく家の中では女房とずっと日本語で会話しているし(英語に上達するためには夫婦でも英語で会話しなさいとよく忠告されるけど、そんなことできないよ)、外に出てすれちがう人がみんな英語を話しているのを耳にして「あ、そうだ、そうだ、ここはアメリカだったんだ」と改めて実感することもしばしばである。毎日机に向かってこせこせと小説を書いているのなら、結局のところ世界中どこにいても同じじゃないかという気がしてくる。

よく「アメリカで書いているのと、日本で書くのとでは、できる小説がずいぶん違うでしょう?」と質問する人がいるけれど、どうでしょうね、それほどのこともないじゃないだろうか。人間というのは、とくに僕くらいの年配になると、生き方にせよ書き方にせよ、よくも悪くも、場所によってガラッと大幅に変われるものではないからだ。とくに僕の場合は「外国に住んでいるから、外国を舞台にした作品を書く」というわけではないのだし。

それに僕はこれまで長いあいだ引っ越しマニアな放浪、非定着の人生を送ってきたので(とくに望んでやっていたわけでもないのだが)、他の人に比べて場所の移動というものがあまり気にならない身体になってしまったみたいだ。考えてみれば、これまでに僕が書いた長編小説はそれぞれぜんぶ違う場所で執筆された。『ダンス・ダンス・ダンス』という小説の一部をイタリアで書いて、一部をロンドンで書いたけれど、どこが違うかと訊かれてもぜんぜんわからない。『ノルウェイの森』はギリシャとイタリアを行ったり来たりしながら書いたけれど、どこの部分をどこの場所で書いたかなんてもうほとんど覚えていない。スコット・フィッツジェラルドは『グレート・ギャッツビイ』の大部分を南フランスで書いたが、ここきわめて優れたアメリカ小説について、執筆された場所を今更気にする人もいないだろう。小説というのはそういうものではないか。 (97-100)

However, as I spend days living this introverted life, I have to say that I’m not overwhelmed with the sense that I’m living in a foreign country. Needless to say, I talk with my wife in Japanese in the house (people often tell me, speak English with your wife to improve, but I can’t do that), and I often realize once again, “Oh yeah, oh yeah, I’m in the U.S.” when I go out and hear people I run into speaking English. If you’re sitting at a desk obsessively writing a novel, in the end I’ve come feel like it doesn’t matter where you are.

People often ask me “The novels you can write in the U.S. and the novels you write in Japan, they must be very different, right?” But I’m not sure, I don’t think they are that much. People, especially once they get up to about my age, don’t suddenly change, whether it’s the way they live or the way they write, for better or worse. And for me especially, it isn’t like I decide to set my work in a foreign country because I’m living in a foreign country.

Besides, I’ve lived a wandering, unattached, moving-obsessed life for a long time (not that I really wanted it that way), so compared to other people my body has become unconcerned with change of place. When I think about it, all of the full-length novels I’ve written to this point were written in different places. I wrote one part of the novel Dance Dance Dance in Italy and one part in London, but I wouldn’t have any idea how they differ if asked. I wrote Norwegian Wood while traveling back and forth between Greece and Italy, but I can hardly remember which part I wrote where. Scott Fitzgerald wrote most of The Great Gatsby in the south of France, but now nobody cares about where this superlative American novel was written. Fiction is that kind of thing.

Pretty interesting. I don’t think I knew that he lived in London. (And, ugh, my translation feels stilted on reread.)

And Murakami is still thinking about the organization-individual dynamic, this time finding the benefit of belonging:

アメリカの大学に所属していて嬉しいことのひとつは、体育館やその他の体育設備がこのようにとても充実していて、しかもそれほど混んでいないことである。東京近郊の民間スポーツ・クラブの混雑と会費の高さを思うと、これはまさに天国と言ってもいいだろう。プールだって時間さえ選べばほとんどの場合二十五メートル・プールの一レーンが一人で好きなだけ使える。僕はこれまでの人生においてどこの組織にも所属してこなかったので、こういう「所属することの喜び」は楽しめるうちにたっぷりと楽しでおこうと思う。アメリカに在住する日本人の大部分は学校に通って熱心に英語を勉強し、せっせと美術館や博物館を訪れるのだが、それに比べてスポーツ・ジムを積極的に利用する人はそれほど多くないという統計が何かに出ていた。もしそれがほんとうだとしたら、これはいささかもったいないことではないか。しかしそう言われて考えてみたら、ケンブリッジに住むようになってから美術館に行ったことなんてたった一度しかない(有名なボストン美術館。大きな声では言えないけれど、

あまり面白くなかった

)。 (101-102)

One of the nice things about belonging to an American university is that the gym and other fitness equipment is top notch, and on top of that not all that crowded. When I think of the crowd and costs of municipal sports clubs in Tokyo, it makes me think I’m in paradise. Take the pool here. Pick a time and in most cases you can use a lane of a 25m pool all to yourself as long as you want. I haven’t belonged to any organization in my life so far, so I’m planning to enjoy the “joy of belonging” as much as I can. There was a statistic that came out somewhere saying most of the Japanese living in the U.S. study hard and industriously visit museums, art or otherwise, but that in comparison there aren’t many who actively use the gyms. Assuming this is true, I feel like it’s a bit of a waste. But it does make me think back and realize that since I’ve lived in Cambridge, I’ve only been to the art museum one time. (The famous Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I shouldn’t say this loudly,

but it wasn’t that great.

)

Murakami gets pretty creative with the text here and actually gives that final clause in a smaller font. Pretty nice. It was tough to recreate in html. I’ve done the best I can. Let me know if you know how to fix it so that I can modify the font size without making it a separate <p>.

I’ve said it once already, and I’ll say it again: Murakami writes well for the Internet age. In many ways he was the first blogger…a writer who interacted with readers and played around with his text. The content, too, is nice and light. These are pretty fun reads.