Welcome to the Tenth Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see past entries in the series here:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat

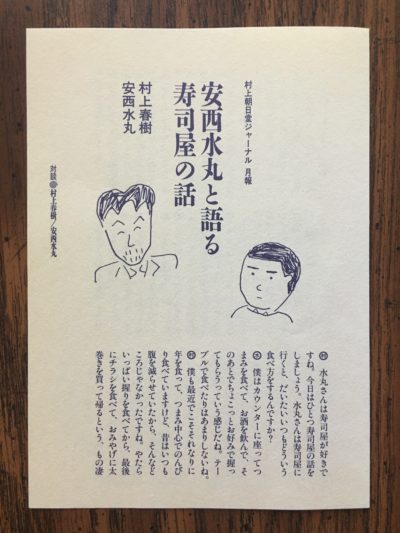

I’ve finished my quick look at some of the essays in Uzumaki neko no mitsukekata and now for the last two weeks I’ll take tidbits from the extra pamphlet included with the text. Take a look:

Murakami has a short conversation with his illustrator Anzai Mizumaru (neé Watanabe Noboru of Yoru no kumozaru fame) about sushi restaurants. The conversation seems to be recorded by “Ogamidori-san” (also of Yoru no kumozaru fame), who also chimes in at a few points.

The first chunk of the interview is about what they like to order, which is only mildly interesting, but then they get into the restaurants themselves:

村 しかしね、水丸さん、寿司屋は味も大事だけど、客層って大事ですよね。

水 そうそう。客層は大事だよ。たとえば小さい子供なんかが隣で生意気にウニばっかり頼んだりしていると、ちょっとむかっとするよね。

村 蹴飛ばしてやりたいですね。それからけばけばした「光り物」糸の女の人が多いとけっこう疲れますよね。香水なんか強いと、ナマものの微妙な味が死んでしまうね。あれはちょっとなんとかしてほしいよな。

水 青山の「海味」の後ろの席でカウンターが空くのを待っているときなんかさ、ちゃらちゃらした「光り物」糸女の背中見ていたりすると、それだけで頭くることあるよね。

村 だんだん腹が立って来たな(笑い)。それから寿司屋によっては、煙草を吸う人が多いですね。あれも辛いですよ。カウンターはできたら禁煙にしてもらいたいと思う。苦しくて苦しくて、何度も途中で出てきた。

水 寿司屋のカウンターでタバコは遠慮するべきだと僕も思う。迷惑だよ。携帯電話も嫌だね。

Murakami: But Mizumaru-san, the food at sushi restaurants is important, but the clientele is also important, isn’t it.

Mizumaru: Yeah, yeah. The clientele is critical. Like, I get annoyed when there’s a bratty little kid next to me who keeps ordering uni.

Mura: I’d want to punt him out of there. And I get worn out when there are hordes of gaudy, “bejeweled” women. The delicate flavor of raw fish just disappears when their perfume is heavy. I wish they’d do something about that.

Mizu: When I’m waiting on the back seat at Umi in Aoyama for the counter seats to open up, staring at the backs of these “bejeweled” women as they jingle and jangle, that’s enough to get to me.

Mura: I’m starting to get angry (laughs). And depending on the restaurant, there are a lot of people who smoke. That’s also tough. I wish they’d make the counter seats no smoking. There’ve been a number of times when I’ve gotten up and left because it was so, so awful.

Mizu: I also think people should hold off on smoking at sushi counters. It’s a nuisance. I also can’t stand cell phones.

The essays were written from 1994-1995 and published as a collection in 1996, well before the no smoking movement (and even the smoking etiquette movement) gained momentum in Japan. On my first visit in 2002, they still had smoking cars on shinkansen. They may still have them, actually.

I tried to track down a photo of someone smoking at a sushi counter, and the best I could do was find this tweet which includes screen grabs from the 1974 drama 『傷だらけの天使』 (Kizu darake no tenshi, Injured Angels):

Actor Atsushi Watanabe deftly chows down on some sushi with a cigarette between the fingers of the same hand. Ahh, those were the days. Ha.

Back next week with one more excerpt from this interview.