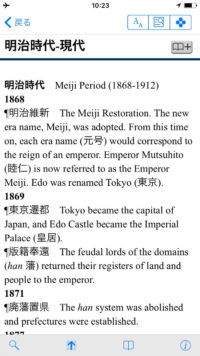

明けましておめでとうございます! Happy New Year! It’s the Year of the Rooster, which apparently is not as lucky for me (a Rooster) as I initially believed…it’s just my responsibility to throw the beans on Setsubun as a 年男. よろしくお願いします!

After an extended break, I’m back on the Murakami with Chapter 33 “Rainy-Day Laundry, Car Rental, Bob Dylan” of Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. It’s a really nice chapter. Watashi waits at the coin laundry for a dryer to open, throws in the Girl in Pink’s laundry when one opens, kills time walking and shopping around the neighborhood, drops off the laundry, picks up some new clothes, has a couple beers at a beer hall, grabs the unicorn skull from storage at Shinjuku Station, rents a car, and drives off to his date.

He spends a lot of time thinking as he performs these activities, and as you might expect, a lot of these thoughts get cut. There are so many that it’s difficult to pick out just one. For the most part I don’t think the cuts detract, and in some cases they actually improve the translation.

One example I’ve already looked at, actually, when I wrote for Neojaponisme about Murakami’s “advertorial” short stories in Men’s Club. There’s an extra bit cut immediately after the passage I looked at. Here is Birnbaum’s version:

I took the subway to Ginza and bought a new set of clothes at Paul Stuart, paying the bill with American Express. I looked at myself in the mirror. Not bad. The combination of the navy blazer with burnt orange shirt did smack of yuppie ad exec, but better that than troglodyte.

It was still raining, but I was tired of looking at clothes, so I passed on the coat and instead went to a beer hall. (342)

And here is the extended original and my translation:

私はまず電車で銀座に出て〈ポール・スチュアート〉でシャツとネクタイとブレザーコートを買い、アメリカン・エキスプレスで勘定を払った。それだけを全部身につけて鏡の前に立ってみると、なかなか印象は悪くなかった。オリーヴ・グリーンのチノ・パンツの折りめが消えかけているのが多少気になるが、まあ何から何まで完全というわけにはいかない。ネイビー・ブルーのフラノのブレザーコートにくすんだオレンジ色のシャツというとりあわせはどことなく広告会社の若手有望社員という雰囲気を私に与えていた。少なくともついさっきまで地底を這いまわっていて、あと二十一時間ほどでこの世界から消えていこうとする人間には見えない。

きちんとした姿勢をとってみると、ブレザーコートの左の袖が右より一センチ半ばかり短いことがわかった。正確には服の袖が短いのではなく、私の左腕が長すぎるのだ。どうしてそうなったのかはよくわからない。私は右ききだし、特に左腕を酷使した覚えもないのだ。店員は二日あれば袖を調節できるからそうすればどうかと忠告してくれたが、私はもちろん断った。

「野球のようなものをやっておられるのですか?」と店員がクレジット・カードの控えを渡しながら私に訊いた。

野球なんかやっていない、と私は言った。

「大抵のスポーツは体をいびつにしちゃうんです」と店員が教えてくれた。「洋服にとっていちばん良いのは過度な運動と過度な飲食を避けることです」

私は礼を言って店を出た。世界は様々な法則に満ちているようだった。文字どおり一歩歩くごとに新しい発見がある。

雨はまだ降りつづいていたが、服を買うのにも飽きたのでレインコートを探すのはやめ、ビヤホールに入って生ビールを飲み、生ガキを食べた。 (500-501)

First, I took the train to Ginza and bought a shirt, a tie, and a blazer at Paul Stuart, paying for it with my American Express. I put it all on and looked at myself in the mirror. Not bad. I was a little worried that the center creases in my olive chinos had started to fade, but I guess not everything had to be perfect. And the combination of the navy blue flannel blazer and burnt orange shirt did make me look a little like a young employee at an advertising firm. But at least I didn’t look like someone who’d just been crawling around in the sewer and only had 21 hours left before he disappeared from the world.

When I stood up straight, I realized that the left sleeve of the blazer was about half an inch shorter than the one on the right. To be more accurate, the sleeve wasn’t shorter, it was my left arm that was longer. How’d I’d gotten that way, I had no idea. I’m right handed, and I had no memory of ever overusing my left arm somehow. The store salesman advised me that they could have the sleeve adjusted in two days and how would that be, but I of course didn’t take him up on the offer.

“Did you ever play baseball or anything?” the salesman asked as he was giving me my credit card receipt.

I told him I’d never played baseball.

“Most sports will deform your body,” the salesman told me. “For Western-style clothes, it’s best to avoid overexercising or overeating.”

I said thanks and left the store. The world is full of different rules. You discover something new literally every step you take.

It was still raining, but I was tired of buying clothes, so I didn’t look for a raincoat and went to a beer hall to drink beer and eat oysters.

I don’t think the translation loses all that much with the cut, but it’s a good example of the heightened awareness Watashi has on his last day. Birnbaum has cut other “discoveries” in the chapter, which start as an extended meditation on potted plants and a snail at the coin laundry. Murakami also uses the word いびつ (ibitsu, warped/deformed), one of his pet vocab words, twice in quick succession. Here in the cut passage and again in the beer hall when he looks in the mirror after using the bathroom.

The most effective cut in translation comes at the end of the chapter, where we know Birnbaum (or his editor) has been especially adept at making changes for more dramatic endings. Here is the Japanese and my translation:

事故現場を抜けるまでにずいぶん長い時間がかかったが、待ちあわせの時刻までにはまだ間があったので私はのんびりと煙草を吸い、ボブ・ディランのテープを聴きつづけた。そして革命運動家と結婚するのがどういうことなのかと想像をめぐらしてみた。革命運動家というのはひとつの職業として捉えることが可能なのだろうか?もちろん革命は正確には職業ではない。しかし政治が職業となり得るなら、革命もその一種の変形であるはずだった。しかし私にはそのあたりのことはうまく判断できなかった。

仕事から帰ってきた夫は食卓でビールを飲みながら革命の進歩状況について話をするのだろうか?

ボブ・ディランが『ライク・ア・ローリング・ストーン』を唄いはじめたので、私は革命について考えるのをやめ、ディランの唄にあわせてハミングした。我々はみんな年をとる。それは雨ふりと同じようにはっきりとしたことなのだ。(508-509)

It took quite a long time to get past the site of the accident, but I had time before I was meeting the librarian, so I just leisurely smoked cigarettes and listened to Bob Dylan. Then I tried to imagine what it would be like to be married to a revolutionary activist. Can a revolutionary activism be considered an occupation? Accurately speaking, of course, revolutionary activism is not an occupation. However, if politics can be an occupation, then revolution should be a modified version of it. But I could never tell very well with things like that.

Would her husband discuss the progress of the revolution over a beer at the dinner table when he got home from work?

Bob Dylan started singing “Like a Rolling Stone,” so I stopped thinking about the revolution and hummed along with the song. We’re all getting older. And it’s as clear cut as the falling rain.

The details about revolutionary activism, which refer back to a high school friend who married an activist and disappeared, feels like a very Watashi Seinfeld-esque aside (“Whats the deal with revolutionary activism?”), and it stands in stark contrast to Birnbaum’s translation:

It took forever to get by the accident site, but there was still plenty of time before the appointed hour, so I smoked and kept listening to Dylan. Like A Rolling Stone. I began to hum along.

We were all getting old. That much as as plain as the falling rain. (346)

Pretty interesting decisions. Seven chapters left…