It’s a month delayed this year, but welcome to the eleventh annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

My calendar tells me it’s been almost a full year since I last blogged about Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, so I think I’ll use this year to try and knock out the last few chapters.

Here are the past entries in the fest:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

I previously used the fest to look at Hard-boiled Wonderland back in 2013 and 2014. This week I’m looking at Chapter 37. You can see the rest of the entries in this series here.

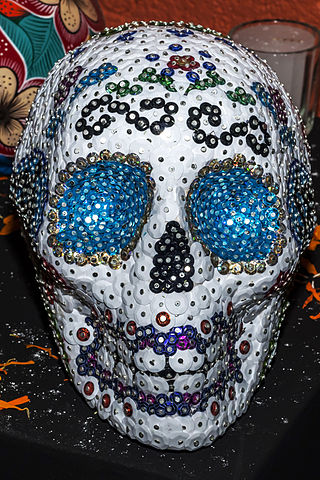

Chapter 37 is titled “Lights, Introspection, Cleanliness.” Watashi is awakened on the couch by the Librarian when she sees that the unicorn skull is emanating lights (just like in the End of the World sections!). They have a couple beers and watch the skull, they talk about how Watashi feels oddly sensitive to small details around him in the world like snails and the way their clothes are piled on the floor. More talk about themselves. They sleep together again (maybe?) and then she falls asleep. Watashi gets up, inspects her kitchen and cooks breakfast while listening to the radio. After they eat, they get cleaned up and ready to head out and Watashi gifts the Librarian the unicorn skull.

There are actually a lot of heavy cuts in this chapter. Birnbaum (or his editor) does his usually thing and adds a space break to provide emphasis. They get rid of the first couple beers they drink; remove most references to the snail which Watashi has noticed and gets fixated on; and cut and adjust lines of dialogue so that it really trims the chapter down.

There’s some wordplay that kind of gets lost in translation. The two keep echoing 悪くない (Warukunai, Not bad, eh?). Birnbaum keeps the first instance but adjusts one in translation and cuts another altogether. This feels like a very Murakami-esque dialogue element, suggesting that, eh, the world ain’t so bad, even though I’ve been screwed over by a massive governmental agency that was experimenting with my brain. Sad to lose the other instances.

And there’s a phrase 清潔で使い道がない (seiketsu de tsukaimichi ga nai, clean and useless) that could be maintained more closely, perhaps.

But then Birnbaum’s prose is just killer in places, such as here:

As dawn drew near, sunlight gradually diminished the cranial foxfires, returning the skull to its original, undistinguished bone-matter state. We made love on the sofa again, her warm breath moist on my shoulder, her breasts small and soft. Then, when it was over, she folded her body into mine and went to sleep. (376)

I mean, damn. You can’t teach that! You can either write like that or you can’t.

Here’s the Japanese…and to be honest, I’m not really sure they have sex again. It seems to be highly suggested based on a clever space break actually provided by Murakami here. Here’s the Japanese:

夜が明けるにつれて頭骨の光は陽光に洗われるようにその輝きを徐々に失い、やがては元の何の変哲も無いのっぺりとした白い骨へと戻っていった。我々はソファーの上で抱きあいながら、カーテンの外の世界がその暗闇を朝の光に奪い去られていく様子を眺めていた。彼女の熱い息が私の肩に湿り気を与え、乳房は小さくやわらかかった。

ワインを飲みほしてしまうと、彼女はその小さな時間の中に身を折り畳むように静かに眠った。… (553)

As dawn began to break, the sunlight gradually washed away the skull’s brilliance, and it returned to its original, smooth, white bone with nothing at all unusual about it. We held each other on the sofa and watched as the darkness of the outside world was lifted by the morning light. Her breath was damp on my shoulder, and her breasts were small and soft.

After she finished the wine, she quickly curled up and quietly fell asleep. …

As you can see, Birnbaum takes a sentence from the subsequent paragraph and combines it with the previous paragraph to kind of complete the narration, whereas Murakami splits it up—in the next paragraph while she falls asleep, he’s wide awake and his attention is on the sounds of the day getting started.

抱き合う (dakiau, hug/embrace or couple, as in “sleep with”) here could easily be sleep with, I think, but it does feel a little strange that way when combined with the second half of the Japanese sentence, which is “watch the room grow lighter.” I mean…if that’s what he was doing, then the sex must not have been that good? What do you all think about this choice?

BOHE also make a very large cut of references to current events at the end of the chapter. Check out the English translation:

She was still getting dressed, so I read the morning paper in the living room. There was nothing that would interest me in my last few hours. (378)

There’s a lot missing in between those two sentences! Here’s the Japanese:

私は彼女が服を着ているあいだ居間のソファーに座って朝刊を読んだ。タクシーの運転手が運転中に心臓発作を起して陸橋の橋桁につっこみ、死んでいた。客は三十二歳の女性と四歳の女の子で、どちらも重傷を負った。どこかの市議会の昼食に出た弁当のカキフライが腐っていて、二人が死んだ。外務大臣がアメリカの高金利政策に対して遺憾の意を表明し、アメリカの銀行の会議はへの貸付け金の利子について検討し、ペルーの蔵相はアメリカの南米に対する経済侵略を非難し、西ドイツの外相は対日貿易収支の不均衡の是正を強く求めていた。シリアがイスラエルを非難し、イスラエルはシリアを非難していた。父親に暴力をふるう十八歳の息子についての相談が載っていた。新聞には私の最後の数時間にとって役に立ちそうなことは何ひとつとして書かれてはいなかった。 (557)

While she was getting dressed, I sat on the sofa in the living room and read the morning paper. A taxi driver had a heart attack while driving, ran into an overpass support, and died. Two passengers, a 32-year-old woman and a 4-year-old girl, both suffered serious injuries. The fried oysters in the bento lunches at a city council somewhere had gone bad and two people died. The Minister for Foreign Affairs expressed his regret over the United States’ high interest rate policies, U.S. banks were meeting to look into the interest rates for loans to Central and South America, Peru’s Finance Minister was criticizing America’s economic penetration into South America, West Germany’s Foreign Minister was insisting on a correction to the trade imbalance with Japan. Syria was criticizing Israel, Israel was criticizing Syria. There was a letter seeking advice about an 18-year-old son who was violent with his father. There wasn’t anything in the paper that seemed of any use to me in my final hours.

Pretty different! Remember that this book was written in 1985 and the translation released in 1991, so the project spans the fall of the Berlin Wall and very nearly the fall of the U.S.S.R. (which went in December 1991). I guess they make this cut because the information isn’t entirely necessary, but it definitely gives the text an entirely different effect.

I wonder if the reality of the current events detracts from the kind of cyberpunkish Tokyo vibe…which is really only present in the scenes with the old man scientist and the thugs. The rest just feels like Tokyo in the 80s. Personally, I like the original and all its breathlessness. It works.

But one of the most thematically notable cuts this chapter is much smaller. Here’s what happens when they see the skull shining:

I gently disengaged her from my arm, reached out for the skull, and brought it over to my lap.

“Aren’t you afraid?” she now asked under her breath.

“No.” For some reason, I wasn’t.

Holding my hands over the skull, I sensed the slightest ember of heat…

And here’s the original Japanese with my translation:

私は右腕を握りしめていた彼女の手をそっとほどいてからテーブルの上の頭骨に手をのばし、それを静かに持ちあげて膝の上に乗せた。

「怖くない?」と彼女が小さな声で訊いた。

「怖くないよ」と私は言った。怖くない。それはおそらくどこかで私自身と結びついているものなのだ。誰も自分自身を怖がったりはしない。

頭骨を手のひらで覆うと、そこにはかすかな残り火のようなあたたかみが感じられた。 (546-547)

I gently released my right arm from her grip, reached out for the skull on the table, and quietly set it on my lap.

“Aren’t you afraid?” she asked quietly.

“Not at all,” I said. I wasn’t afraid. Somehow, someway it was connected to my being. No one is afraid of their essence.

When I placed my hands over the skull, I could feel a faint warmth, like some sort of embers.

I imagine that an editor made a cut here and got rid of the 私自身, either because it felt awkward and unnecessary or it was too on the nose. It’s not an easy thing to translate well. I think translating it simply as “myself” doesn’t work because perhaps some of us are afraid of ourselves. I wondered if “my self” would work, but that strikes me as something that might confuse the reader and look more like a mistake. Any ideas on how you might address this?

Very interesting stuff this chapter, one that could serve as a microcosm of the translation of the whole novel. Three chapters left!