Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

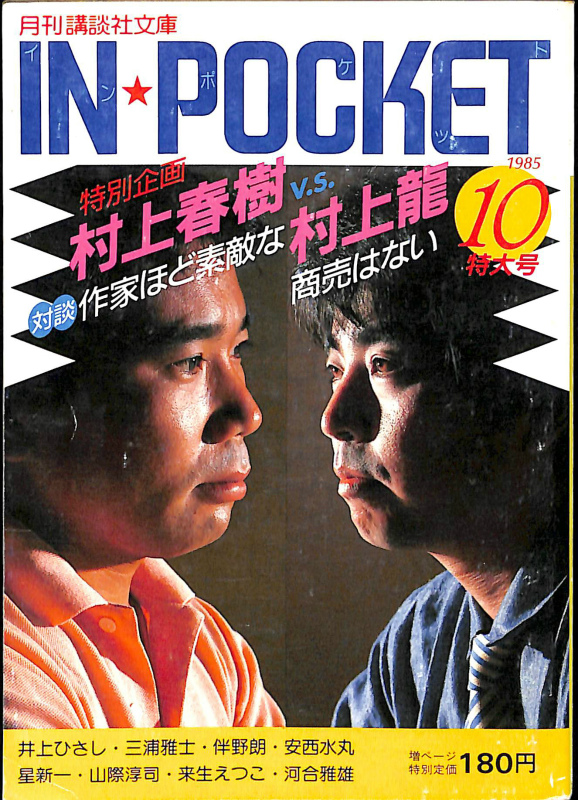

Year Eight: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

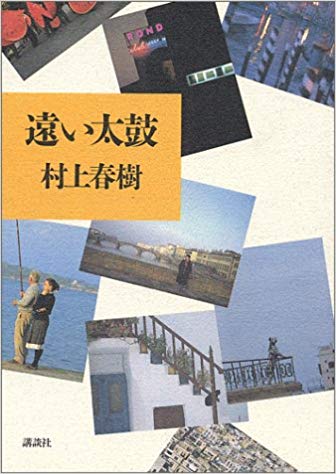

Year Nine: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year Ten: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year Eleven: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year Twelve: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense

100 pages into the memoir, Murakami has settled into life on the island and takes a chapter to capture his daily routines titled “A Day in the Life of a Novelist on Spetses” (スペッツェス島における小説家の一日).

Here’s a section from the beginning:

Once I finish breakfast, I run. At least 40 minutes, and at most about 100 minutes. When I get back I take a shower and get to work. While I’m on this trip, I’m planning to work on two translations, a set of travel sketches (like what I’m writing here), and a new novel. So I don’t have much free time at all. I work on my manuscript for a bit, and when I get bored I move to the translation. When I get bored of the translation, I work on the manuscript again. It’s like going to a rotemburo on a rainy day. When I start to feel light headed, I get out of the water, and when I get cold I get back in. This goes on and on. (110-111)

朝食が済むと走る。短くて四十分、長くて百分ぐらい。帰ってきてシャワーを浴び、仕事にかかる。今回の旅行中に仕上げる予定でいるのは翻訳二冊ぶんと、旅行のスケッチ(今書いているような文章)と、それから新しい長編小説。だから決して暇ではない。自前の原稿をしばらく書いてそれに飽きると翻訳に移る。翻訳作業に飽きると今度はまた自前の原稿を書く。雨の日の露天風呂と同じである。のぼせると湯から出て、冷えると湯に入る。延々とつづけられる。 (110-111)

It’s interesting to read about his daily routines. I feel like I read a different account that was like this but separated fiction and translation more cleanly into morning and afternoon activities – translation was something he said he could do once he’d already been somewhat exhausted by the work of writing fiction. I can’t seem to track down that passage.

After running and writing, Murakami and his wife walk into town. He gives a narrative account of the walk, describing the buildings, shops, and sights. They stop at a cafe and read the paper. Murakami makes friends at the restaurants and small stores, including one well-captured profile of a shop owner who helps him with his Greek and gets very curious about the camera he has with him.

Murakami makes lunch, his wife makes dinner. He goes fishing in between using stale bread and feta cheese as bait, as taught by the friendly store owner. Sometimes they eat out. And then there’s a lovely little ending to the chapter:

When we finish dinner, it’s already pitch dark outside. I read and listen to music in the living room, and my wife adds an entry to her journal, writes letters to friends, does our budgeting, or makes bizarre complaints like, “Gahh, I can’t stand this. I’m sick of getting older.” On cold nights we light a fire in the fireplace. Time passes quietly and comfortably as we zone out and stare at the fire. The phone doesn’t ring, and there are no deadlines. There’s no TV, either. There’s nothing. Just the crackling of the fire as it pops and hisses in front of us. The silence is blissful. We empty a bottle of wine, and after a straight whiskey, I get a little tired. I look at the clock, and it’s nearly 10:00. And then I just drift into a pleasant sleep. The day feels like I did so much and yet also like I did nothing at all. (123)

夕食が終わると外はもう真暗になっている。僕は居間で音楽を聴きながら本を読み、女房は日記をつけたり友だちに手紙を書いたり、お金の計算をしたり、「あーやだやだ、歳をとりたくない」などとわけのわからない愚痴を言ったりしている。寒い夜は暖炉に火を入れる。暖炉の火を眺めつつぼんやりとしていると、時は静かに気持ち良く過ぎ去っていく。電話もかかってこないし、締切りもない、テレビもない。何もない。目の前でパチパチと火がはぜているだけである。沈黙がひどく心地好い。ワインを一本空にし、ウィスキーをグラスに一杯ストレートで飲んだところで、いささか眠くなる。時計を見るとそろそろ十時である。そしてそのまま気持ち良く眠ってしまう。いっぱい何かをしたような一日であり、まるで何もしなかったような一日である。 (123)

The mention of the phone and deadlines ties in nicely with the earlier sections of the memoir. The tone here reflects how much has changed. Short, clear sentences, as compared with the longer, breathless ones from the earlier sections that reflect the chaos of the move and of life in Tokyo.

That’s it for Murakami Fest 2019! Already looking forward to next year and taking another close look at Murakami’s travels.