The last two weeks have been…interesting. I had been following the coronavirus developments in China through work and then in Japan through work, friends, and acquaintances. But it did seem like it might be contained to Asia for a minute.

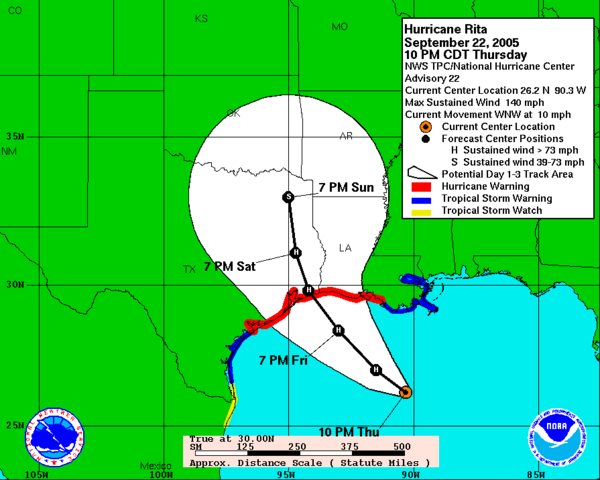

It’s such a blur now—everything: the day job which has been busy and challenging and fulfilling, the writing I’ve been doing for the Japan Times, the hustle to stock up my apartment, trying to exercise and sleep and relax—that I can’t even remember when I started to sense the “cone of uncertainty,” as we say in New Orleans.

The cone is the graphic that meteorologists deploy when hurricanes start to approach the Gulf coast. They use a number of different storm models to create a wide path where the hurricane is likely to hit. Once that cone starts to point at New Orleans, you either get out or you prepare to hunker down and shelter in place.

My mom is a legendary evacuator, and my dad is a legendary hunker-downer/waiter-outer. So I am kind of wired for prep. Once I felt the cone, from news reports, from articles, I made a plan.

I think I’m in a good place. I can work from home for as long as I need to, and I don’t really need to leave my apartment if I don’t want to. (Obviously that much care is probably not required – I’m in a Chicago neighborhood, so the density is probably enough to take walks and get some air on the lake or in parks nearby, maybe even do some shopping if necessary.)

This is my monthly update to plug my Japan Times work, so it feels bizarre to me to line these two headlines up next to each other:

“’Emergency’ Japanese can help build fluency”

“Your Japanese vocabulary can expand as the new coronavirus spreads”

I didn’t mean “emergency” in that sense of the word. But that would make a good article, too. One that I’m not sure I feel comfortable writing without doing some research — I haven’t been in a Japanese clinic for a while.

The emergency article is a strategy that I thought up to develop more familiarity with complex phrases. I specifically wanted to prepare for a May conference that now may not end up happening. Or at the very least, I may not end up attending. The strategy itself feels sound, although the results will vary based on the repetitions you do with your document. (I just did a lap through right now after feeling bad for neglecting it over the past couple weeks.)

The coronavirus article came together quickly with some research, and I was a little surprised by what I found. The emphasis on 肺炎 (haien, pneumonia) is interesting and notable in Japanese. In English it’s just this vague virus, and lots of association with the flu, which feels like fever, chills, and a kind of generic run-down illness. Pneumonia, on the other hand, is much more specific, especially to someone like me who has had it before.

I got bacterial pneumonia during my first year on the JET Program. I remember it pretty vividly. It hit late on a Friday night, which was about the worst time for it to hit, especially since the following Tuesday was a holiday. I had a couple beers, watched “The Godfather” on NHK, and went to bed. I woke up drenched in sweat and feverish. I spent the weekend going in and out of fever as I went through my ibuprofen and tried to negotiate some sort of balance of warmth in my apartment using the kerosene heater. I drove into Aizu-Wakamatsu and had McDonalds, did some shopping in the city, and called in sick on Monday.

By Tuesday I still hadn’t slept off whatever it was I had, and I was alternating between burning up and terrible chills, so I got in touch with my supervisor to ask about how to go to the town clinic. The doctor there was a young guy with a full beard, and he was only able to diagnose the pneumonia with an x-ray. It was a mild enough case that he had trouble detecting it with a stethoscope.

This is all to say that pneumonia is terrible, and I can’t even imagine what an acute case would feel like. Stay indoors. Isolate yourself. Work from home. If you start to feel like your workplace is putting you in a dangerous position, make an executive decision and stand up for yourself. Sometimes all you have to do is ask—it doesn’t have to be confrontational or personal. You can be calm and professional and assertive at the same time.

Ugh. Fun times!

__

On a separate note, I have two pieces in the new print edition of Neojaponisme.

The first is an excerpt from the massive look at the Top 50 Enka songs I did back in 2017. (19 of the 50 videos are still up on YouTube, which is a higher percentage than I expected! You can find the others [hopefully] with the PERMASEARCH links I cleverly left. Thank you, past Daniel!) I highly recommend listening through these songs. You’ll learn a TON of useful Japanese and perhaps even find a few tunes that you can use to impress the locals.

They also asked me to translate a conversation between Jacques Derrida and Japanese scholars Karatani Kōjin and Asada Akira about deconstruction. To be perfectly honest, I’m not even sure I understand what the English means, but I am confident that David and Matt helped me smooth over the language so that it is a decent representation of the Japanese.

I’m still digging through this volume, but Ian’s design is incredible, I’m hungry for the 洋食 (yōshoku, Japanese take on Western food) described within, and I can’t wait to check out Matt’s translations, including one from Tanizaki. Highly recommend picking up a copy.