Welcome to the Seventh Annual How to Japanese Murakami Fest!

With the goal of stirring up even more interest in Murakami between now and October, when the Nobel Prizes are announced, I will post a small piece of Murakami translation/analysis/revelation once a week from now until the announcement. You can see past entries in the series here:

Year One: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year Two: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year Three: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year Four: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year Five: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year Six: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year Seven: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons

Chapter 21 “Bracelets, Ben Johnson, Devil” continues. Watashi and the Girl in Pink make it through the waterfall and to the laboratory, but it’s been ransacked like everything else. Watashi is convinced that they took the old man as well until the girl goes into the closet to show him the secret exit. Birnbaum’s translation:

The girl went to the closet in the far room and threw the hangers onto the floor. As she rotated the clothes rod, there was the sound of gears turning, and a square panel in the lower right closet wall creaked open. In blew cold, moldy air.

“Your grandfather must be some kind of cabinet fetishist,” I remarked.

“No way,” she defended. “A fetishist’s someone who’s got a fixation on one thing only. Of course, Grandfather’s good at cabinetry. He’s good at everything. Genius doesn’t specialize; genius is reason in itself.”

“Forget genius. It doesn’t do much for innocent bystanders. Especially if everyone’s going to want a piece of the action. That’s why this whole mess happened in the first place. Genius or fool, you don’t live in the world alone. You can hide underground or you can build a wall around yourself, but somebody’s going to come along and screw up the works. Your grandfather is no exception. Thanks to him, I got my gut slashed, and now the world’s going to end.”

“Once we find Grandfather, it’ll be all right,” she said, drawing near to plant a little peck by my ear. “You can’t go back now.”

The girl kept her eye on the INKlink-repel device while it recharged. (210)

It’s been a while since I last read this book, so I was a little surprised at this point to see that she actually kisses him. I remember her being a horndog, but I didn’t remember any physicality. Here is the Complete Works version and my translation:

娘は奥の部屋に行ってクローゼットの中にかかっていたハンガーを床に放り出し、ハンガーをかけるステンレス・スティールのバーを両手でつかんでくるくるとまわした。しばらくそれをまわしているうちに、歯車のかみあうかちんという音が聞こえた。それからもなお同じ方向にまわしつづけていると、クローゼットの壁の右下の部分が縦横七○センチほどの大きさにぽっかりと開いた。のぞきこんでみるとその穴の向うには手にすくいとれそうなほどの濃い暗闇がつづいているのが見える。冷ややかなかび臭い風が部屋の中に吹きこんでくるのが感じられた。

「なかなかうまく作ってあるでしょ」と娘がステンレス・スティールのバーを両手でつかんだまま、私の方を向いて言った。

「たしかによくできてる」と私は言った。「こんなところに脱出口があるなんて普通の人間じゃ考えつかないものな」

彼女は私のそばに寄って背のびし、私の耳の下に小さくキスをした。彼女にキスされると私の体はいくらかあたたまり、傷の痛みもいくぶん引いたように感じられた。私の耳の下にはそういう特殊なポイントがあるのかもしれない。あるいはただ単に、十七歳の女の子に口づけされたのが久しぶりだったせかもしれない。この前十七歳の女の子に口づけされたのは十八年も前の話である。

娘はじっと発信機の目盛りをにらんでいたが、やがて「行きましょう」と私に行った。充電が完了したのだ。(289-290)

The girl went to the closet in the far room, threw out all the hangers, and began to rotate the stainless steel bar with both hands. As she turned it, there was the clink of gears engaging. She continued turning the bar in the same direction, and a square of about 70cm or so popped open in the lower right section of the closet wall. I peeked in and beyond the opening I could make out a darkness so thick I could’ve scooped it up into my hands. A musty chill blew into the room.

The girl turned to me with the bar still in her hand. “Pretty impressive, huh?” she said.

“It certainly is,” I said. “Normal people would never expect an escape hatch in somewhere like here.”

She came over to me, stood on her toes, and gave me a peck just beneath my ear. When she kissed me, my body grew warmer, and it felt like the pain in my wound also faded slightly. Maybe there was some kind of special point just below my ear. Or maybe I simply hadn’t been kissed by a 17-year-old girl in a long time. It had been 18 years since I’d last been kissed by a 17-year-old-girl.

The girl stared at the charge on the INKling repelling device and finally said, “Let’s go.” The charging was complete.

Interesting. Birnbaum (or his editor) cut the interiority after the kiss. It’s just a peck and then she keeps talking. He thinks nothing of it.

As you can see, though, Murakami makes his own cuts in the Complete Works edition. When there’s smoke there’s fire, so I was super curious to check out the Japanese paperback original for “cabinet fetishist” and to see which parts both BOHE and Murakami cut. Here we go (my translation follows):

娘は奥の部屋に行ってクローゼットの中にかかっていたハンガーを床に放り出し、ハンガーをかけるステンレス・スティールのバーを両手でつかんでくるくるとまわした。しばらくそれをまわしているうちに、歯車のかみあるかちんという音が聞こえた。それからもなお同じ方向にまわしつづけていると、クローゼットの壁の右下の部分が縦横七十センチほどの大きさにぽっかりと開いた。のぞきこんでみるとその穴の向うには手にすくいとれそうなほどの濃い暗闇がつづいているのが見える。冷ややかなかび臭い風が部屋の中に吹きこんでくるのが感じられた。

「なかなかうまく作ってあるでしょ」と娘がステンレス・スティールのバーを両手でつかんだまま、私の方を向いて言った。

「たしかによくできてる」と私は言った。「こんなところに脱出口があるなんて普通の人間じゃ考えつかないのな。まさにマニアックだな」

「あら、マニアックなんかじゃないわよ。マニアックというのはひとつの方向なり傾向なりに固執する人のことでしょ?祖父はそうじゃなくて、あらゆる方面に人より優れているだけなのよ。天文学から遺伝子学からこの手の大工仕事までね」と彼女は言った。「祖父のような人は他にはいないわ。TVやら雑誌のグラビアやらに出ていろいろと吹聴する人はいっぱいいるけれど、そんなのはみんな偽物よ。本当の天才というのは自分の世界で充足するものなのよ」

「しかし本人が充足しても、まわりの人間はそうじゃない。まわりの人間はその充足の壁を破って、なんとかその才能を利用しようとするんだ。だから今回のようなアクシデントが起るんだ。どれだけの天才でもどれだけの馬鹿でも自分一人だけの純粋な世界なんて存在しえないんだ。どんなに地下深くに閉じこもろうが、どんなに高い壁をまわりにめぐらそうがね。いつか誰かがやってきて、それをほじくりかえす。君のおじいさんだってその例外じゃない。そのおかげで僕はナイフで腹を切られ、世界はあと三十五時間あまりで終わろうとしている」

「祖父がみつかればきっと何もかもうまく収まるわ」彼女は私のそばに寄って背のびし、私の耳の下に小さくキスをした。彼女にキスされると私の体はいくらかあたたまり、傷の痛みもいくぶん引いたように感じられた。私の耳の下にはそういう特殊なポイントがあるのかもしれない。あるいはただ単に、十七歳の女の子に口づけされたのが久しぶりだったせかもしれない。この前十七歳の女の子に口づけされたのは十八年も前の話である。

「みんなうまくいくって信じていれば、世の中に怖いものなんて何もないわよ」と彼女は言った。

「年をとると、信じることが少なくなってくるんだ」と私は言った。「歯が擦り減っていくのと同じだよ。べつにシニカルになるわけでもなく、懐疑的になるわけでもなく、ただ擦り減っていくんだ」

「怖い?」

「怖いね」と私は言った。それから身をかがめて穴の奥をもう一度覗き込んだ。「狭くて暗いのは昔から苦手なんだ」

「でももううしろには引き返せないわ。前に進むしかないんじゃないかしら?」

「理屈としてはね」と私は言った。私はだんだん自分の体が自分のものではなくなっていくような気分になりはじめていた。高校生の頃バスケット・ボールをやっていて、ときどきそういう気分になったことがあった。ボールの動きがあまりにも速すぎて、からだをそれに対応させようとすると、意識の方が追いついていけなくなってしまうわけだ。

娘はじっと発信機の目盛りをにらんでいたが、やがて「行きましょう」と私に言った。充電が完了したのだ。 (361-363)

The girl went to the closet in the far room, threw out all the hangers, and began to rotate the stainless steel bar with both hands. As she turned it, there was the clink of gears engaging. She continued turning the bar in the same direction, and a square of about 70cm or so popped open in the lower right section of the closet wall. I peeked in and beyond the opening I could make out a darkness so thick I could’ve scooped it up into my hands. A musty chill blew into the room.

The girl turned to me with the bar still in her hand. “Pretty impressive, huh?” she said.

“It certainly is,” I said. “Normal people would never expect an escape hatch in somewhere like here. You’d have to be a total maniac.”

“Hey, he’s no maniac,” she said. “A maniac is someone who fixates on a certain thing or tendency, right? Grandfather isn’t like that; he’s superior on all different levels. From astronomy to genetics and even carpentry like this. There’s no one else like Grandfather. There are tons of people who appear on TV or in magazines to try and promote themselves, but they’re all a bunch of phonies. True geniuses are fulfilled by their own world.”

“But even if geniuses are fulfilled, the people around them aren’t. The people around them try to break down the walls of that fulfillment and use their genius for something. And that’s why accidents like this happen. You don’t exist in a world that’s purely your own no matter how smart or how stupid you are. No matter how deep underground you dig, no matter how high of a wall you try to surround yourself with, right? Eventually someone will come along and try to expose you. Your grandfather isn’t any exception. Thanks to him, I got my gut slashed, and the world is going to end in just over 35 hours.”

“Once we find Grandfather, it will all work out.” She came over to me, stood on her toes, and gave me a peck just beneath my ear. When she kissed me, my body grew warmer, and it felt like the pain in my would also faded slightly. Maybe there was some kind of special point just below my ear. Or maybe I simply hadn’t been kissed by a 17-year-old girl in a long time. It had been 18 years since I’d last been kissed by a 17-year-old-girl.

“If you just trust that everything will work out, there’s nothing in the world that can scare you,” she said.

“As you get older, you trust in fewer things,” I said. “It’s like the way your teeth wear down. You don’t get cynical or skeptical, just worn down.”

“Are you scared?”

“I am,” I said. I squatted down and looked in the hole again. “I can’t stand dark and cramped spaces.”

“But we can’t go back. We can’t only keep going, right?”

“In theory,” I said. I gradually started to get the feeling that my body was no longer my own. I occasionally had that sensation when I was playing basketball in high school. The ball moved too fast, and when I tried to make my body keep up, my consciousness got left behind.

The girl stared at the charge on the INKling repelling device and finally said, “Let’s go.” The charging was complete.

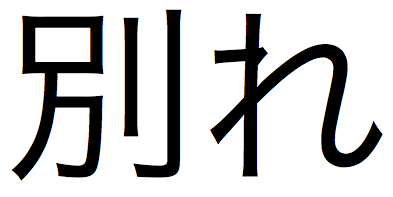

So “fetishist” is literally “maniac” in the Japanese. I think Birnbaum’s fetishist is a better translation. I left it as maniac to give non-Japanese readers a better sense of the passage. The only other possibility in English is “zealot,” perhaps.

As you can see, Murakami cuts the discussion of genius in its entirety for the Complete Works edition, and Birnbaum has adapted it somewhat liberally above in his version. It’s too bad that the line about trust gets cut: say what you will about Murakami as a writer, in his younger days he did write compellingly about what it feels like to get older.

And it’s nice to see his pet images the well and the wall in the original paperback version.

I wasn’t quite sure about the implications of 吹聴, but I took it to mean “experts” who are always making appearances on TV or in magazines, partly to share their knowledge but also to build their brand.

As mentioned last week, next week’s cut is a doozy. Can’t wait to take a closer look at it.