Year 1: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year 2: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year 3: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year 4: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year 5: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year 6: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year 7: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

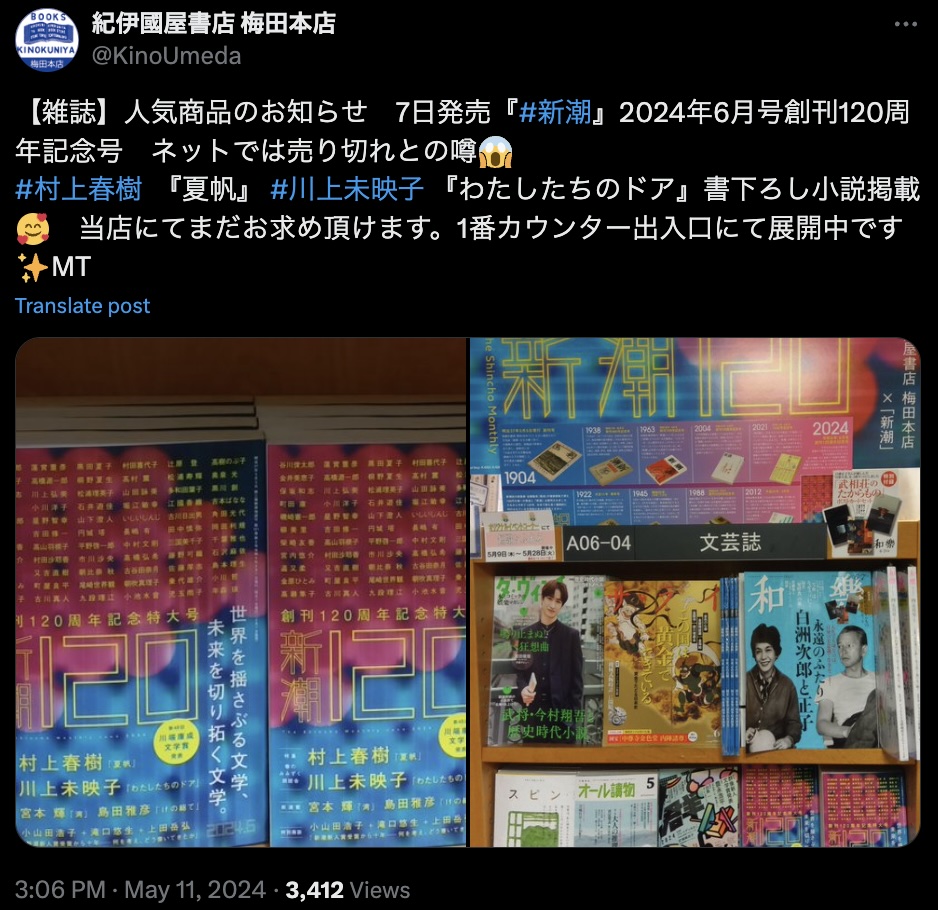

Year 8: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year 9: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year 10: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year 11: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year 12: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense, Rotemburo

Year 13: Murakami Preparedness, Pacing Norwegian Wood, Character Studies and Murakami’s Financial Situation, Mental Retreat, Writing is Hard

Year 14: Prostitutes and Novelists, Villa Tre Colli and Norwegian Wood, Surge of Death, On the Road to Meta, Unbelievable

Year 15: Baseball on TV, Kindness, Murakami in the Asahi Shimbun – 日記から – 1982, The Mythology of 1981, Winning and Losing

Year 16: The Closet Massacre, Booze Bus, Old Shoes, Editing Norwegian Wood, Prophecy

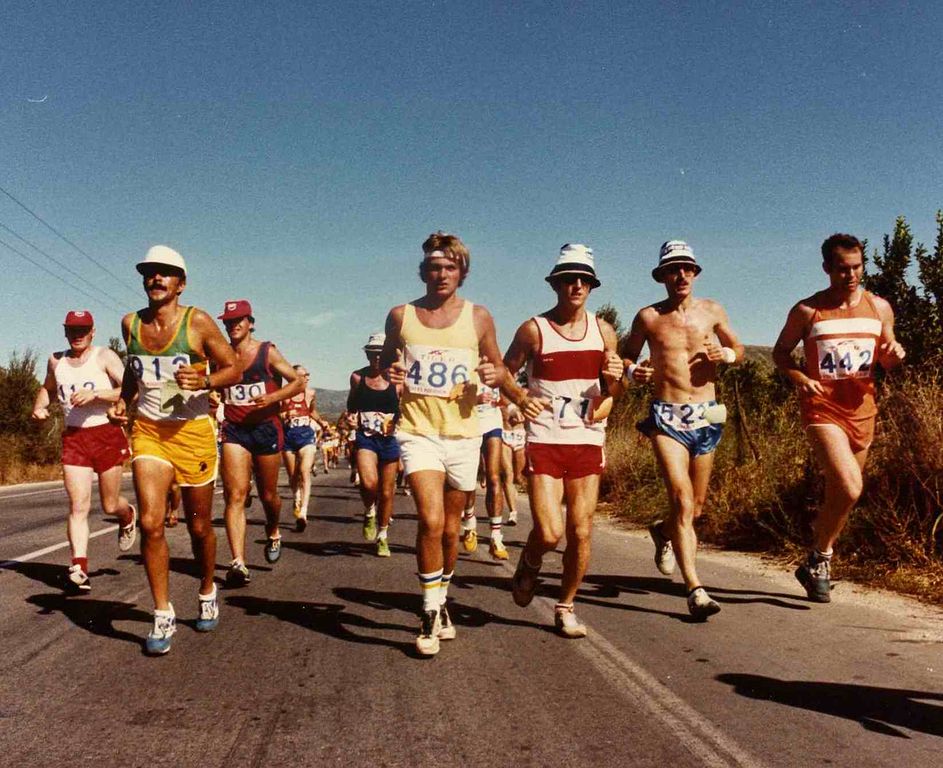

Year 17: Athens Marathon 1987, Infinite Appetites

Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

In the next chapter, カヴァラからのフェリーボート (The Ferry from Kavala), Murakami rides the ferry from Kavala to Lesbos. It’s notable for the point of view which really focuses in on Murakami himself, and not his wife. He’s on the ferry and notices a group of young Greek soldiers. They’re always riding ferries, although he doesn’t have a good idea of where they’re going.

There’s a nice scene describing the young soldiers laughing and smoking cigarettes. Murakami writes them sympathetically because he’s been thinking about fighting ever since the Evros River incident, which happened the December of 1986 (the year prior).

He goes on a little aside about the futility of war before being brought back to his senses by a Greek man who points at the television:

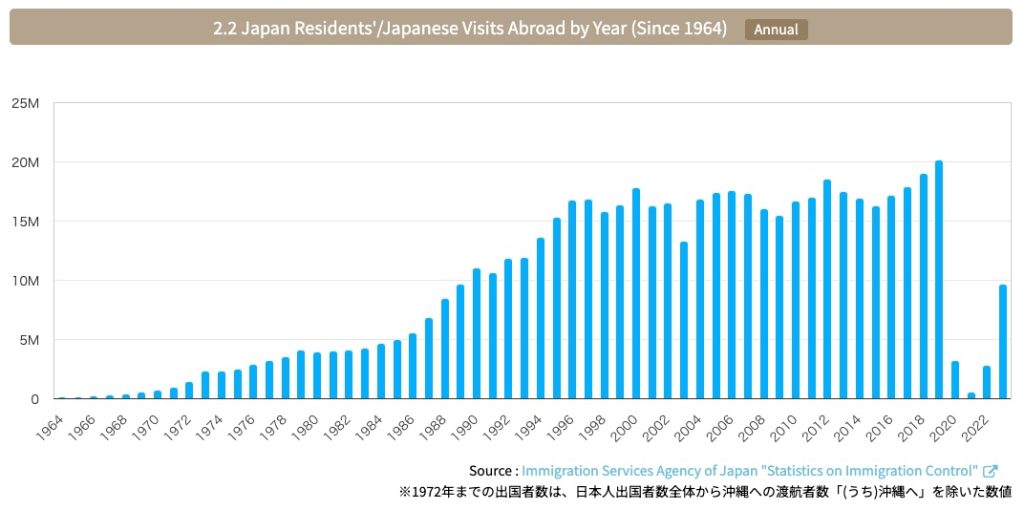

The middle-aged Greek man seated at the table next to me says, Hey, look at the TV, it’s Japan. The news on the TV in the first-class lobby is showing the Tokyo Stock Exchange in Kabutocho. People with rigid looks on their faces are shouting something. They’re pointing. Their sleeves are rolled up, and they’re yelling into phones. But I’m unable to figure out what’s going on. “It’s money,” the Greek man says in broken English, “Money.” He pantomimes counting out money. I take it that stocks have crashed. But I can’t explain the details with my level of English. (* I realized this later, but this was Black Monday. When I think about it, I’m reminded of F. Scott Fitzgerald. In 1929, Fitzgerald learned of the Great Crash when he was traveling in Tunisia. He describes it “like distant thunder.” Of course, Black Monday wasn’t anywhere close to the scale of the 1929 crash, but I still remember feeling a sort of sense of unease. I might’ve been thinking about war just at that moment, so the stock crash and everyone’s paralyzed faces on TV may have felt more darkly ominous than usual to me.)

隣のテーブルに座っている中年のギリシャ人が僕に向かってほら、テレビを見てごらんよ、日本だよ、と言う。一等船室のロビーのテレビのニュースが東京兜町の証券取引所の光景を映し出している。こわばった顔つきをした人々が何かを叫んでいる。指を上げている。シャツの袖をまくりあげて、電話に向かって何か怒鳴っている。でも何のことだか僕には理解できない。「moneyだよ、money」とギリシャ人が片言の英語で言う。そして金を勘定する仕種をする。どうやら株が暴落したらしい。でも詳しいことは僕の英語力では説明できない。(*あとになってわかったことだが、それが例のブラック・マンデーだった。僕はこのときのことを思い出すたびに、スコット・フィッツジェラルドのことを考える。スコット・フィッツジェラルドは1929年の大暴落をチュニジアを旅行している時に知った。「まるで遠い電鳴のように」と彼は描写している。もちろん、ブラック・マンデーは規模として1929年の暴落とは比べ物にならなかったけれど、その時のなにかしら不安定な空気のことを僕はまだ記憶している。たぶんちょうどそのとき戦争のことを考えているので、株の暴落とテレビの画面に映る人々のひきつった顔が、僕には余計に暗く不吉に思えたのだろう) (296)

That’s essentially the end of the chapter. There’s a brief news segment on the TV about Prime Minister Nakasone stepping down for Prime Minister Takeshita. Red Dawn starts to play after the news. And Murakami returns to his cabin after eating a pear and crackers and drinking some brandy. He awakes in Lesbos.

This is an interesting chapter because of the F. Scott Fitzgerald connection and because Black Monday happens to be my birthday. So when I turned 6, Murakami was asleep on a ferry in the Aegean Sea.

I’m unable to track down the Fitzgerald quote, so that’s my translation of Murakami’s Japanese. If anyone knows where I might find that Fitzgerald writing (it seems to be his journal/diary rather than a piece of published writing), let me know!