Week 4 of Murakami Fest 2025. See past posts here.

In the last chapter, we got an episodic look at a few days before Christmas in Rome. Next Murakami gives us an overall view of the whole winter in this chapter titled “Winter Deepens” (冬が深まる). He starts writing Dance Dance Dance on December 17 and spends all winter writing as he battles off multiple colds. But the writing goes pretty well.

年も押し迫った十二月十七日から『ダンス・ダンス・ダンス』という長編小説を書き始める。

長編小説を書くときはいつも同じパターンである。「書きたいな」というぼんやりとした気持ちが自分の中で少しずつ高まってきて、そしてある日「さあ、今日から書こう」ときっぱりと思う。僕の場合、細かい構成とか筋書きよりは、この臨界点の見極めを大事にする。

『ノルウェイの森』とは違って、『ダンス・ダンス・ダンス』の場合は書き始める前にまずタイトルが決まった。このタイトルはビーチボーイズの曲から取ったと思われているようだが、本当の出所は(どちらでもいいようなものだけれど)ザ・デルズという黒人パンドの古い曲である。

日本を出発する前に、家にある古いレコードをひっかき集めて自家製オールディーズ・テープを作っていったのだが、その中にこの曲がたまたま入っていた。いかにも昔風リズム・アント・ブルースというタイプの曲である。のんびりとしていて、ざらっとした雑な感じで、その辺が不思議に黒っぽい。その曲をローマで毎日聴くともなくぼんやり聴いているうちに、タイトルにふとインスパイアされて書き始めたのだ。もちろんピーチポーイズにも同じ題の曲があることは知っていたけれど(高校生のときによく聴いた)、直接的な始まりはこのデルズの曲の方である。

この小説は始めから終わりまでだいたいすんなりと気持ち良く書けたと思う。『ノルウェイの森』は僕としてもそれまでに書いたことのないタイプの作品だったし、「この小説はいったいどういう風に受け入れられるんだろう」とあれこれ考えながら書いたのだけれど、この『ダンス・ダンス・ダンス』に関しては、そんなことはまったく考えずに、自分の書きたいようにのびのびと好きに書いた。隅から隅まで僕自身のスタイルの文章だし、登場してくる人物も『風の歌を聴け』『1973年のピンポール』『羊をめぐる冒険』と共通している。だから久し振りに自分の庭に戻ってきたみたいで、すごく楽しかった。というか、書くという行為をこれほど素直に楽しんだことは、僕としても稀である。(334-335)

As the year drew to a close, I began writing a novel titled Dance Dance Dance on December 17.

Whenever I write a novel, it’s the same pattern. The feeling that “I want to write” gradually builds somewhere within me, and then one day, I decide, “All right, today we start to write.” For me, being able to discern this critical point is more important than having a detailed structure or a plot.

Unlike Norwegian Wood, with Dance Dance Dance, I chose the title before I started writing. Many believe I took this title from the Beach Boys song, but the actual source was an old song by the African-American band The Dells (although it doesn’t matter much which of the two it was).

Before I left Japan, I made some homemade oldies tapes from old records I scratched together around the house, and that song was on one of them. It’s an old school R&B song through and through. It’s relaxed and kind of rough, which gives it a strange darkness. I just kind of had that song on in the background every day when I was in Rome, and I started writing inspired by the title. Of course I knew that the Beach Boys had a song with the same title (I listened to it when I was in high school), but the direct beginning was this Dells song.

From start to finish, writing this novel was a smooth, pleasant experience. Norwegian Wood was a kind of writing I’d never done before, so while I was writing, I kept wondering, “What the heck are people going to think of this?” but with Dance Dance Dance, that never entered my mind and I wrote without any worries exactly the way I wanted to write. Every last sentence is my own style, and the characters are the same as in Hear the Wind Sing, Pinball, 1973, and A Wild Sheep Chase. So it felt like returning to a garden I’d kept after a long while. It was a lot of fun. I guess even for me it’s rare to enjoy the act of writing in such a straightforward way.

Such an interesting, rich passage. Murakami’s experience strikes me as both very modern and at the same time ancient. Music had become more portable than it would have been 20 and maybe even just 10 years prior (the Walkman came out in 1979) when he would have had to bring all his records, but it still requires Murakami to do some work. These days we have access to our entire collections—and basically the entirety of all human musical output—in a single pocketable device. Music conversion concerns are extinct when it comes to international moves, except for very niche and marginal exceptions.

The idea of Murakami wandering around Europe hooked up to a constant cycle of jazz, classical, and R&B, on the other hand, is an idea that feels very familiar and is basically identical to my experience living in Japan from 2003-2010, more or less. From around 2008 or so onward, I did start to include podcasts in my regular rotation, but I had a Discman when I studied abroad and rented CDs from Tsutaya. On JET, I was still collecting CDs (and went notably deep into Thelonious Monk) but had iPods I could stock with songs.

I wonder about distraction. Murakami must’ve been distracting himself with music to a certain extent, just as I was/am. It makes me want to seek boredom, in a very Craig Mod-inspired way. Maybe that would be best.

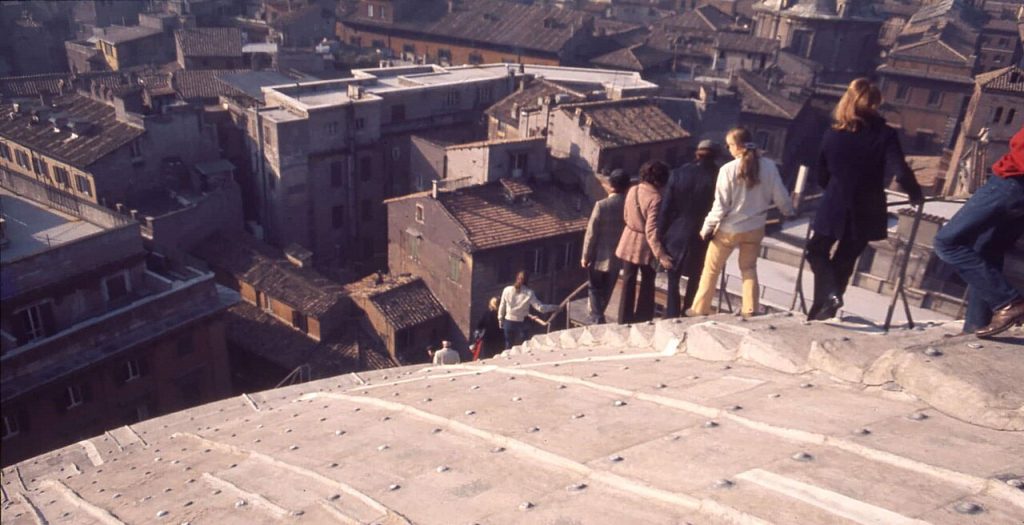

The rest of the chapter is about the miserable winter. They end up catching a cold after standing in line for four hours to get tickets to see Maurizio Pollini, who ends up being underwhelming. Murakami mentions a superlative Tokyo performance by Sviatoslav Richter as a contrast.

He notes that writing in the cold is the opposite of what writing Norwegian Wood was like, and mentions he’s writing on a word processor:

僕はあまりに寒いのでオーパーコートを着て机に向かい、ぱたぱたとワートプロセッサーのキイを叩きつづけた。シシリーで『ノルウェイの森』を書いたときとは正反対である。あのときは暖かくて暖かくて、机に向かいながら、頭がぼおっとしていた。今回は寒くて、ワードプロセッサーのキィを打ちそこねるくらいである。(336)

I was so cold that I wore an overcoat at my desk as I punched away at the keys on the word processor. It was the polar opposite of writing Norwegian Wood in Sicily. It was so, so hot then that I found my mind wandering off while sitting there. This time it was so cold that I thought I might break the keyboard.

The Murakamis spend the winter dreaming of onsen and life in Hawaii, which is actually the reason that Dance Dance Dance features scenes in Hawaii; Murakami was trying to mentally stave off the cold. But he notes that he cannot return to Japan until the novel is complete. Once he starts, he has to keep going: 日本に帰ったら、またペースが乱されてしまう (337). (If I went back to Japan, my pace would be totally thrown off.)

A couple other very minor notes. Murakami mentions the bombing of Korean Air 858 and the dollar weakening to 123 yen. They were keeping their cash in dollars, so this affects their day to day to a certain extent, although I assume most of Murakami’s earnings were in yen, which would have been to his benefit. This is the period of time when the dollar-yen exchange rate dropped into the range that we’re currently familiar with after spending decades in the 200-360 yen/dollar range.