Year 18 of Murakami Fest. Murakami Fest can legally vote. Wild. See the previous entries in Murakami fest here. This year, I’m continuing my look at his travel memoir Distant Drums.

The Murakamis are back in Rome for the winter, and the first thing on the to-do list is buying a television in this chapter titled “TV, Gnocchi, Prêtre” (テレビ、ニョッキ、プレートル). Murakami says he needs a more active source of news, particularly for the transportation information (there are lots of strikes) and the weather. In Japan he could just dial a number on the phone to get access to the information.

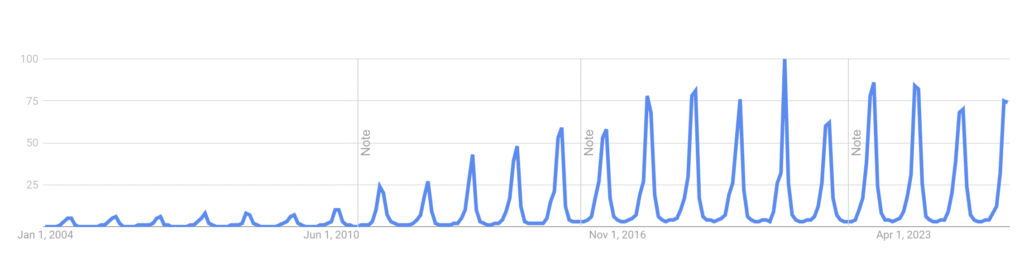

Strangely enough, it looks like this service may have just ended. NTT, at least, ended their 177 service on March 31 of this year after being in service for 70 years. An NHK news article notes that the usage of this service peaked in 1988 (the last year of Murakami’s trip to Europe) at over 300 million calls and fell to 5.56 million by 2023 (which still seems like a lot!). Thus, our bizarre look at Japan’s history through Murakami’s travel memoir continues.

Murakami spends some time describing Italian public TV and the newscasters who are all quite animated and colorful (which he claims to be able to detect despite the fact that he buys a black and white TV).

He then shifts into a trip to Bologna for gnocchi. He highlights how pleasant it is to travel there because there are fewer tourists and because he’s found some decent restaurants. He ends the chapter with two music anecdotes. After watching The Sicilian in Bologna, he walks through town and stumbles on a Lee Konitz concert in the basement of a random osteria. Unfortunately it’s sold out. Later, back in Rome, he and his wife go to see Georges Prêtre conducting the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia.

This chapter is only OK. The sections on Italian TV—in particular the dramatic, aging weatherman—are probably the most interesting, but they border on caricature. The Bologna trip is mostly told in exposition. But taken together, there are two interesting stories that speak to the buying power of the yen, the economic mindset that Murakami was in at the time, and the (universal-ish?) experience of having life in a foreign country influence your perception of costs.

First, Murakami talks about buying a TV, and he’s operating on a particularly Japanese mindset:

でもわざわざ高いテレビを買うのもばかばかしいから、まず近所の中古電気屋をのぞきにいく。日本の量販店なんかだと小さいテレビなら二万円くらい出せば買えるからそのつもりで行ったのだが、これが思ったよりかなり高い。やたらでかくって古色蒼然としたのが三万円もする。画像もちょっとぼけてる。日本だったら絶対にスクラップという代物である。僕は昔、これよりずっと鮮明に映るやつを国分寺駅近くのごみ捨て場で拾って帰ったことがある。仕方ないから一番安い白黒の新品を買うことにした。ニュースと天気予報がわかりゃいいんだから色なんてあってもなくても同じである。 (314-315)

But it would also be ridiculous to buy an expensive television, so first I checked out the local used electronics store. At the big box stores in Japan, you could pick up a small TV for about 20,000 yen, so that’s what I had in mind when I went, but they were much more expensive than I thought. A TV much larger than I needed with a dim, faded screen ran 30,000 yen. The picture was a little warped as well. If this was Japan, it would’ve been on the scrapheap. A long time ago, I managed to go home with a TV with much clearer picture that I picked up at a garbage drop off near Kokubunji Station. Now I didn’t have a choice, so I decided to but the cheapest new black and white model. All I needed it for was the news and weather report, so it made no difference if it was color or not.

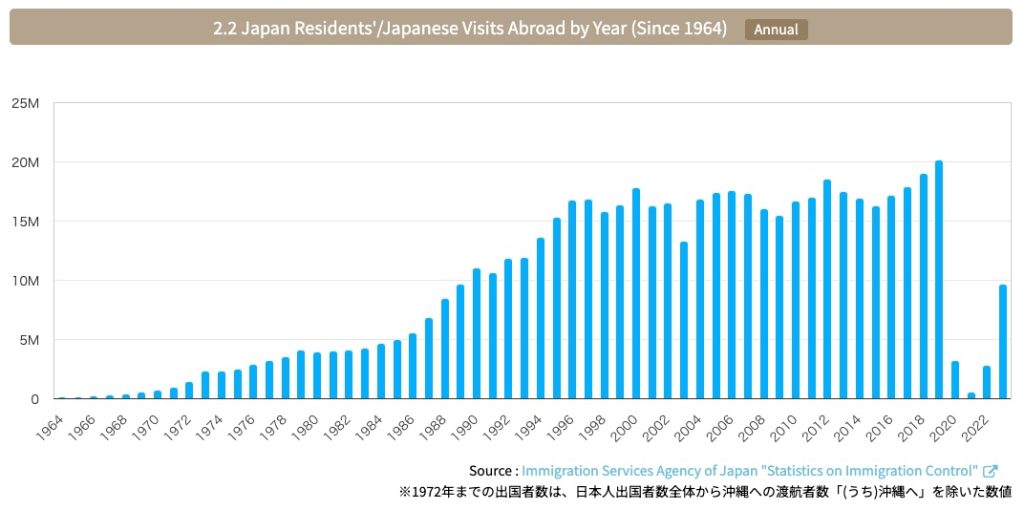

This reminds me of an anecdote from Matt Alt’s book Pure Invention of being able to score very lightly used electronics on trash day in Bubble-era Japan. Interesting to see Italy in a very different situation when it comes to the ubiquity of electronics and their costs.

It does seem like living in Italy has started to influence Murakami’s perception of costs a bit. He’s potentially started to anchor toward the cheaper cost of living, as shown when he goes to get tickets for the orchestra:

十二月六日、日曜日、ローマでジョールジュ・プレートル指揮の聖テチリア・オーケストラを聴きに行く。演奏曲目はベートーヴェンの交響曲の五番と六番という凄まじいというか何というか、かなりのものだけれど、年末でもあることだしベートーヴェンをまとめて聴くのも悪くないんじゃないかという感じで前日にヴァチカンの前にある聖チェチリアのホールまで切符を買いに行った。値段は5500円、3900円、2200円だが残念ながらいちばん高い券しか残っていない。それも前例のはしっこの方である。それで女房と二人で随分迷ったのだけれど、年末だからまあいいか(何がどういいのかよくわからないけど)、とあきらめて買ってしまう。どうしてかはわからないけれど、外国にいると知らず知らずだんだん生活がつつましくなってくる。東京にいると一万円のチケットでもさっさっと買っちゃうのに。 (321)

On Sunday, December 6, we went to hear Georges Prêtre conducting the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome. The selection was Beethoven’s 5th and 6th Symphonies—which I guess you might qualify as staggering works, at any rate quite major—it was the end of the year, and hearing a number of Beethoven pieces at once sounded like it would be nice, so the day before we went to Saint Cecilia Hall in front of the Vatican to buy tickets. The prices were 5,500 yen, 3,900 yen, and 2,200 yen, but unfortunately only the most expensive were left. And those were on the edge of the front row. My wife and I had a lot of trouble making up our minds, but it was the end of the year so we thought it was fine (what was fine, I couldn’t say exactly), so we ended up buying them. I don’t know why, but when we’re living in a foreign country, our lifestyle gets increasingly frugal without even realizing it. Despite the fact that in Tokyo we’d shell out 10,000 yen for a ticket without a second thought.

So the cost of electronics is expensive in Italy, but the orchestra is relatively affordable. The opposite of in Japan. To provide some reference, in December 1987, the yen was around 130 JPY/USD.