Year 1: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year 2: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year 3: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year 4: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year 5: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year 6: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year 7: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year 8: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year 9: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year 10: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year 11: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year 12: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense, Rotemburo

Year 13: Murakami Preparedness, Pacing Norwegian Wood, Character Studies and Murakami’s Financial Situation, Mental Retreat, Writing is Hard

Year 14: Prostitutes and Novelists, Villa Tre Colli and Norwegian Wood, Surge of Death, On the Road to Meta, Unbelievable

Year 15: Baseball on TV, Kindness

I swore I’d look at a shorter piece of writing after reading a lengthy 対談 last week, and to a certain extent I did: Murakami’s writing for the Asahi Shimbun’s 日記から (Nikki kara, From my journal) column are probably less than 400 characters each. The column ran six days a week in the evening edition, and different writers were commissioned for various lengths of time. Murakami wrote 12 pieces over two weeks from March 29, 1982 to April 10, 1982.

The quality of writing varies. There are a few gems, and others where Murakami just spins his wheels.

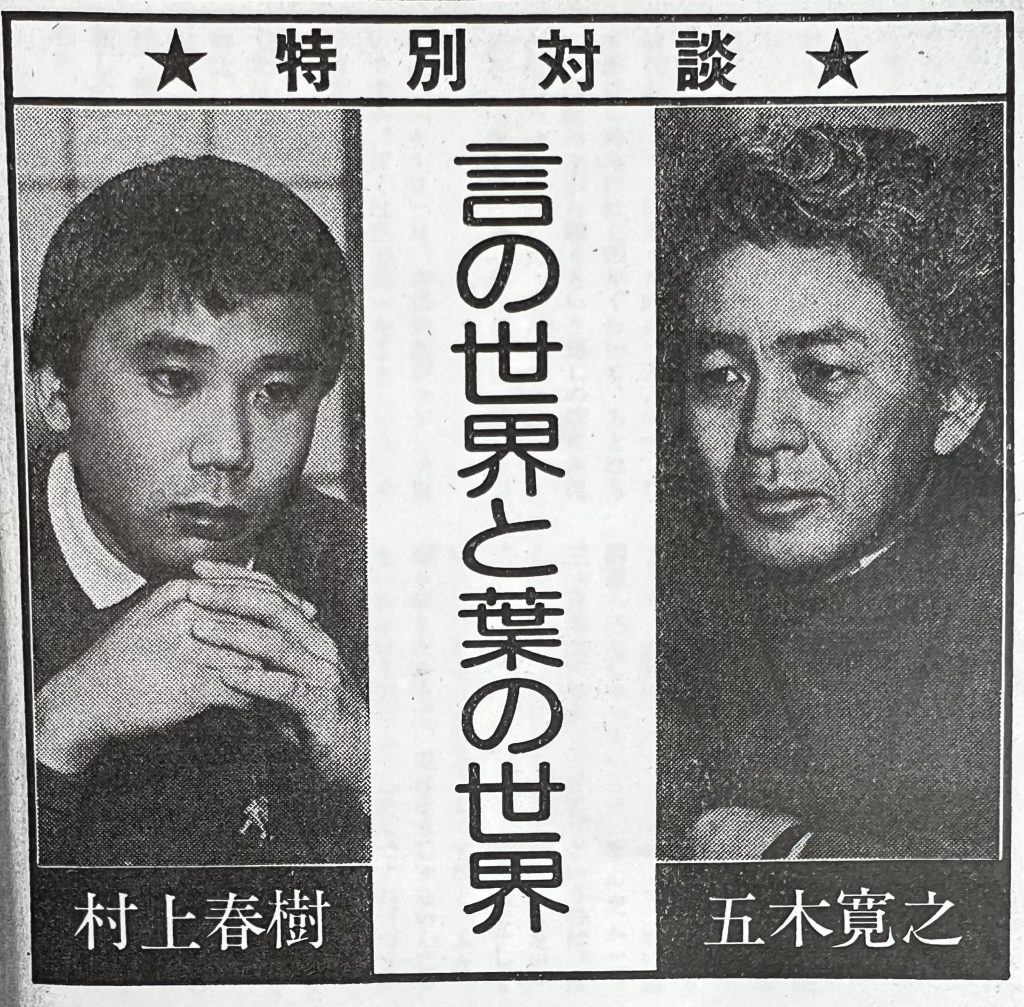

Rather than pick out one representative, I thought I’d give an overview of each and a few quotes here and there. That feels more helpful to characterize this moment in time. The series as a whole is an interesting look at Murakami early in his career. Before diving in, take a minute to think about the context here. This is Murakami writing a micro-essay in the paper of record (albeit the evening edition) for two weeks straight, six months before A Wild Sheep Chase, his third novel, would be published and draw the attention we saw with the conversation with Itsuki Hiroyuki last week. I imagine the editors had a need to fill word count, but it’s still pretty remarkable.

Rather than pick out one representative, I thought I’d give an overview of each and a few quotes here and there. That feels more helpful to characterize this moment in time. The series as a whole is an interesting look at Murakami early in his career. Before diving in, take a minute to think about the context here. This is Murakami writing a micro-essay in the paper of record (albeit the evening edition) for two weeks straight, six months before A Wild Sheep Chase, his third novel, would be published and draw the attention we saw with the conversation with Itsuki Hiroyuki last week. I imagine the editors had a need to fill word count, but it’s still pretty remarkable.

March 29, 1982

力の論理 (The Logic of Power)

Murakami begins by talking about how discrimination in Japan is invisible until you actually experience it. As an example, he writes about trying to rent an apartment as a bar owner and being associated with prostitution. This transitions to a discussion of public vs private power, and that the fight for power is what inevitably led to the atom bomb. He quotes from Itoi Shigesato here (「そーゆー意味なら、原爆がいっちゃん強いわ」, “By thaaat reasoning, the A-bomb is the trumpiest card”), but I can’t track down where it’s from.

March 30, 1982

まねき猫 (Maneki-neko)

This is one of my favorites. Here’s the first paragraph with a deep Murakami v Murakami trivia:

The Abyssinian kitten I got last summer from Murakami Ryū has become enormous. Its appetite and physical strength are astounding, which has given the other cats a bit of a complex.

昨年の夏に村上竜のところから来たアビシニアンの仔猫がすっかり固太りして大きくなった。食欲も体力も相当なものなので他の猫は少々ノイローゼ気味である。

Murakami goes on to talk about his maneki-neko collection and how he responds to people who ask about what the raised hand means (“A raised right hand means they take cash, and a raised left hand means they take checks.”)

March 31, 1982

アイシテマース (Ai shitemaasu)

Murakami was listening to a record of Quincy Jones at the Budokan, and toward the end Jones turns to the audience and says:

“Ai shitemaasu, ai shitemaasu, dōmo, dōmo”

「アイシテマース、アイシテマース、ドーモ、ドーモ」

Murakami has opinions about this; he understands why Jones is saying it and what the goal is, but: “It’s courtesy, but it’s a little strange” (「愛敬ではあるが、ちょっと変だ」)

When musicians say “I love you” it’s “I love you” as recognition of a shared experience. Basically it’s sexy. “Ai shitemaasu” isn’t sexy. It’s fundamentally a mistake. “Ii yo, Ii yoo” is actually closer.

ミュージシャンの発する“I LOVE YOU”は共有体験を確認するための“I LOVE YOU”である。要するにセクシーなのだ。「アイシテマース」はセクシーではない。そこが根本的に間違っているのだ。「イイヨ、イイヨオ」の方がまだ近い。

In a typical essayistic 展開, Murakami shifts this to a bigger picture idea:

For something on the level of “Ai shitemaasu,” courtesy is the conclusion. However, taking something that isn’t an equivalent and giving it a place as an equivalent is a dangerous line of thinking. “Japanese spirit with Western learning” is the most extreme example. The extreme Europeanism in modern Japan and the ultra nationalist response are, at once, the cost of mistakenly hitting this button.

「アイシテマース」程度なら愛敬で済む。しかし等価に置き得ないものを等価に置いて対峙させるというのは危険な発想である。たとえば「和魂洋才」などという座標軸はこの最たるのである。日本近代における極端な欧化主義とその反動としてのウルトラ・ナショナリズムは、ともにこのボタンのかけちがえの代償である。

April 1, 1982

感性の思想 (The Idea of Taste)

A pretty boring piece here. Murakami talks about different senses/aesthetics/tasets and how he hates when people shut down conversations by saying, “We have totally different tastes.” His main point here:

Taste isn’t a status symbol, but rather an entrance ticket to wider self recognition. The act of taking that step is the same for everyone. Everything after that is the problem.

感性はステータス・シンボルではなく、より開かれた自己認識への入場券である。入場するという行為は等価である。それから先が問題なのだ。

April 2, 2022

不思議猫の存在 (The Strange Existence of Cats)

I think this is probably my favorite piece. It reads like a piece of fiction. In the first paragraph, Murakami claims his Siamese cat was talking in her sleep and said, “Didn’t I tell you so” (

「だってそんなこと言ったって」).

He goes on:

You may not believe me, but it’s the truth. I was sitting next to her reading a book and was momentarily taken aback, unable to respond.

When I thought about it later, I realized it must have just sounded that way. There’s no other explanation.

信じてもらえないだろうが、これは事実である。僕は隣で本を読んでいたのだが、しばらく呆然として口もきけなかった。

あとになって考えてみれば、偶然そんな風に聞こえたんだろうということになってしまう。それ以外に考えられないからである。

The rest of the piece is dedicated to cats’ strangely surreal presence.

April 3, 1981

表札とモラトリアム (Name Plates and Moratoriums)

Murakami starts by noting three things he doesn’t like spending money on: cars, TVs, and nameplates for houses, so he’s never purchased any of these. (There’s a funny aside on picking up a TV off the street only to return it.) He goes on to describe how a friend guilts him in to buying a nameplate (“You don’t go to cabaret clubs or travel abroad. That’s too extreme. The least you can do is buy a nameplate.”) He goes to a department store but doesn’t find any he likes, so:

There wasn’t anything else to do, so I had a Shōkadō bento and went home. As I sat there by myself eating a Shōkadō bento in a department store, I felt keenly that I’d become an adult. However, I still didn’t have a nameplate.

仕方ないから食堂で松花堂弁当を食べて帰ってきた。デパートの食堂で一人で松花堂弁当を食べていると、僕も大人になったんだなとつくづく思う。しかし表札はまだない。

A nice little Murakami moment.

April 5, 1982

山羊座の宿命 (The Fate of Capricorns)

Murakami’s take on horoscopes. He’s a Capricorn, which always gets him characterized as hardheaded. Here’s the main line:

I’d be fine with, I don’t like that you’re hardheaded. However, people who say, You’re hardheaded because you’re a Capricorn and I hate it, are completely hopeless.

ムラカミは頭が固くてダメだ、というのはいい。しかし、ムラカミは山羊座だから頭が固くてダメだ、というのでは救いようがないではないか。

April 6, 1982

グンニーリク田島

This is a funny little meditation on Japanese font printed on vehicles. I had so much trouble deciphering the title until I started reading and realized that it’s spelled backwards. The essay has a funny final line about the dry cleaners referred to in the title:

However, it would be a surprise if it was actually a second-generation Norwegian.

しかし意外に本当のノルウェーの二世だったりするのかもしれない。

April 7, 1982

長距離型せっかち (The Long-distance Impatient)

Murakami writes about how he’s impatient/hasty (せっかち, sekkachi) by nature. He always meets deadlines, sometimes writes articles before leaving on a trip to do reporting, is always early for appointments, etc. He divides impatient people into two categories – long-distance and short-distance – claiming that he’s in the first category. He’s not short tempered. He likes running marathons and prefers writing novels to short stories. His wife is short-distance impatient. For example, she checks the garden the day after planting seeds.

This is a nice little essay, but I didn’t feel the need to quote anything.

April 8, 1982

教師という存在 (The Idea of Teachers)

Murakami writes that he’s always had a distrust of teachers because his father was one. He has studied more as an adult than as a student, but he does remember two particularly good teachers. The first was a high school English teacher:

In high school, my grades in English were bad, but I had a teacher who explained the meaning of the word “appreciate” so incredibly lucidly that it opened my mind and I thought, “So that’s what English is.” After that, I learned how to read English.

高校時代は英語の成績が悪かったのだが、ある先生がappreciateという単語の意味を極めて明快に解説するのを聞いて「そうか、英語とはこういうものか」と目の前がさあっと開ける思いをしたことがある。それ以来英語が読めるようになった。

And the other was his thesis professor, whom he met for the first time when he turned in his thesis (those were the times, he notes):

That teacher said, “Have you considered a career involving writing?” At the time I thought it was impossible, so I laughed it off, but when I turned 29, I happened to remember what he said and felt like trying to write. When I tried, I somehow managed to write.

その先生に「君は文章を書く職業についたらどうだい」と言われた。まさかと思ったからその時は笑ってごまかしたのだが、二十九になった時にふとそれを思い出して文章を書いてみる気になった。書いてみたら、なんとか書けた。

In the final line, he shouts out the teachers by name. I wonder if they ever saw it!

April 9, 1982

図書館雑観 (Thoughts on Libraries)

Murakami starts by talking about how embarrassing it is to find a book you wrote in a library (not to brag, lol), but then says he loves libraries and goes on to say he prefers paying taxes for services like that as opposed to the JSDF. He ends by wondering if the guards at bases have guns with live rounds and whether they have the authority to fire them.

Eh, it’s fine. No need to quote it.

April 10, 1982

モラル・マジョリティー (Moral Majority)

Murakami writes about how Reagan’s “moral majority” has started to go after The Catcher in the Rye. The explanation is basic but necessary for a Japanese audience. He talks about curse words, how the rhythm and meaning are difficult to translate into Japanese, and then introduces a line from the Japanese translation of Vonnegut’s Slapstick that he thought captured the original. The translation includes the word おまんこ, which I would not recommend Googling at work. He thus ends his two week in a pretty vulgar way. Here’s the final sentence:

The word “Omanko” is pretty cute, don’t you think? Maybe not?

「おまんこ」という言葉はなかなか可愛いと思いませんか?駄目かな。

So that’s where Murakami is as a writer, almost three years exactly since he won the prize for his first novel (May 1979). He’s ironing out his sense of humor (arguably), but he’s got a knack for capturing the ennui of modern Japan in very little space.

Rather than pick out one representative, I thought I’d give an overview of each and a few quotes here and there. That feels more helpful to characterize this moment in time. The series as a whole is an interesting look at Murakami early in his career. Before diving in, take a minute to think about the context here. This is Murakami writing a micro-essay in the paper of record (albeit the evening edition) for two weeks straight, six months before A Wild Sheep Chase, his third novel, would be published and draw the attention we saw with the conversation with Itsuki Hiroyuki last week. I imagine the editors had a need to fill word count, but it’s still pretty remarkable.

Rather than pick out one representative, I thought I’d give an overview of each and a few quotes here and there. That feels more helpful to characterize this moment in time. The series as a whole is an interesting look at Murakami early in his career. Before diving in, take a minute to think about the context here. This is Murakami writing a micro-essay in the paper of record (albeit the evening edition) for two weeks straight, six months before A Wild Sheep Chase, his third novel, would be published and draw the attention we saw with the conversation with Itsuki Hiroyuki last week. I imagine the editors had a need to fill word count, but it’s still pretty remarkable.