Welcome to Murakami Fest 2022! This is my first Murakami Fest in Japan since 2009, which is pretty wild. I kept this ridiculous project going for 12 years outside of Japan. At times it was the driving force behind this blog and a motivation to keep writing. I think it’s paid off. This is also Year 15! Completely bonkers. Here are the past posts:

Year 1: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year 2: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year 3: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year 4: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year 5: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year 6: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year 7: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year 8: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year 9: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year 10: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year 11: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year 12: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense, Rotemburo

Year 13: Murakami Preparedness, Pacing Norwegian Wood, Character Studies and Murakami’s Financial Situation, Mental Retreat, Writing is Hard

Year 14: Prostitutes and Novelists, Villa Tre Colli and Norwegian Wood, Surge of Death, On the Road to Meta, Unbelievable

This year I’m taking a little break from 遠い太鼓 (Distant Drums). In June, I had the chance to go to the National Diet Library…twice.

View this post on Instagram

I was partially motivated to go because of the food there. While the famous sixth-floor 食堂 (shokudō, cafeteria) is gone, the other cafes provide an extremely close approximation. My usual pattern is to have a late second breakfast of あんバター (anbatā, anko and butter) toast and then an even later lunch of some sort of 洋食 (yōshoku, western food). This time I did an omelette curry and a Napolitan on my two visits.

Getting back to the main point, I spent my days there digging around in Murakami’s early, largely uncollected bibliography. For me, this is really the most interesting part of Murakami’s history as a writer. From 1979 to 1992, Murakami was insanely prolific. He wrote random one-off essays, articles, profiles, interviews, travel writing, etc, etc. The pace ended up exhausting Murakami and drove him out of Japan to Europe. This much we know from reading Distant Drums. Over the next five weeks, I’ll introduce a few of the pieces I dug up from this period.

Heading to the National Diet Library in search of Murakami is something I probably would have done on my own at some point, but I had a very specific catalyst this year. David Marx shared this Instagram post in his stories a few months ago. Scroll on through to the last image in the post. Recognize that picture?

View this post on Instagram

I managed to zoom in on the image and…what did I happen to see? Well, let me show you.

This is a June 1981 interview/profile of Murakami in the magazine “Checkmate” with the title 二つのことを両立させるのは難しいけど、自分で決めたことだから (It’s difficult to balance both [writing and running a jazz cafe], but that’s what I chose).

The interview finds Murakami at a crossroads. In June 1981, he had written two novels and was, presumably, working on A Wild Sheep Chase, which would be published just over a year later, but he was also running Peter Cat, his jazz cafe, full time. He mentions in the interview that he has almost no downtime. Just enough to go out drinking every now and then. He dreams of paying off his loan and owning the cafe and his house so he wouldn’t have to pay for rent. In ten years or so he wants to live in Hokkaido (sounds like he’s at least started thinking about A Wild Sheep Chase!). He doesn’t want to put out low quality work – he hates amateurism. He doesn’t even watch high school baseball. He wants to break down literature that’s too carefully crafted and move the art forward.

This is all fine, and sounds an awful lot like the Murakami we’re all familiar with, but there’s one thing from this interview that stands out. Here’s the first question the interviewer asks Murakami:

What was your most immediate motivation for writing a novel?

Well, it was basically that I thought I might be able to write one. I was watching baseball on TV. It was a pleasant, sunny April day. I was 29 years old. I wanted to do something before I turned 30.

I got married as a student when I was 21. For the seven years I was studying at Waseda, when I thought about getting a job, it felt like I’d have to hate my wife to not find some kind of work. I loved jazz, and a had I ton of records, so I felt like I might be able to run a jazz cafe, which is why I started one. I really worked to save up money.

——— He responds so nonchalantly: I thought I might be able to write a novel, run a jazz cafe. As the interviewer, I wanted to draw a little more out of him, but when I’ve been interviewed myself in the past, I gave similar responses. I finally was able to see that he embodied the desire to live without a care in the world.

小説を書いた触接動機?

ふとね、書けるかなと思った訳です。TVで野球見ていたんです。気持ちの良い、四月の晴れた日。二十九歳でした。三十になる前に何かやりたかった。

二十一歳のときに、学生結婚したんですよ。早稲田に七年通って、就職のコト考えていたときカミさんがイヤなら就職しないでいいって言う訳。ジャズが好きで、レコード数多く持ってたし、ジャズ喫茶ならやれるかなって、始めた訳です。一生懸命、お金ためましたよ。

――小説は書けるかなって思って、ジャズ喫茶も出来るかなって思って、と答える彼。インタビューをする僕としては、もう少し聞きだしたい気がするのだが、かつて僕自身がインタビューされた時も似た様な答え方をしている。さりげなく生きていこうという気持ちの表れであることがやがて理解できた。

Holy Destruction of the Murakami Myth, Batman! He was watching baseball on TV?! That upends the story that Murakami has been telling about himself for decades. That he was sitting at Jingu Stadium, having a beer, watching the Swallows, and Dave Hilton hit a double, prompting Murakami to think that he could write a novel.

Obviously this could be the interviewer’s fault. The article is very clearly a composite. Sections of more or less quoted/lightly paraphrased material Frankensteined together with the occasional comment from the interviewer. It’s been edited for space, and sometimes the transitions don’t make complete sense. It’s highly unlikely the interviewer recorded the conversation, so they were probably going by whatever notes they took.

That said, it’s pretty wild to see the story change. A year earlier, for example, in a conversation with Murakami Ryū he had said he saw the game live, which is the story he’s stuck by since.

The only other notable element is that Murakami takes a moment at the end of the interview to show off his feminist bona fides and notes that the Murakamis split the chores in their household, just like John Lennon did.

I’ll leave you with the interviewer’s final comment, which is pretty nice:

Murakami admits that he doesn’t like writing, which I take to mean that he can’t go easy on himself. The novels this man writes are, at the moment, quietly drawing in readers.

文章を書くことは好きじゃないと漏らしていた村上氏、自分にあまえてはいけないという意味だろうか。そんな彼の書く小説が今、静かに読者をひきつけている。

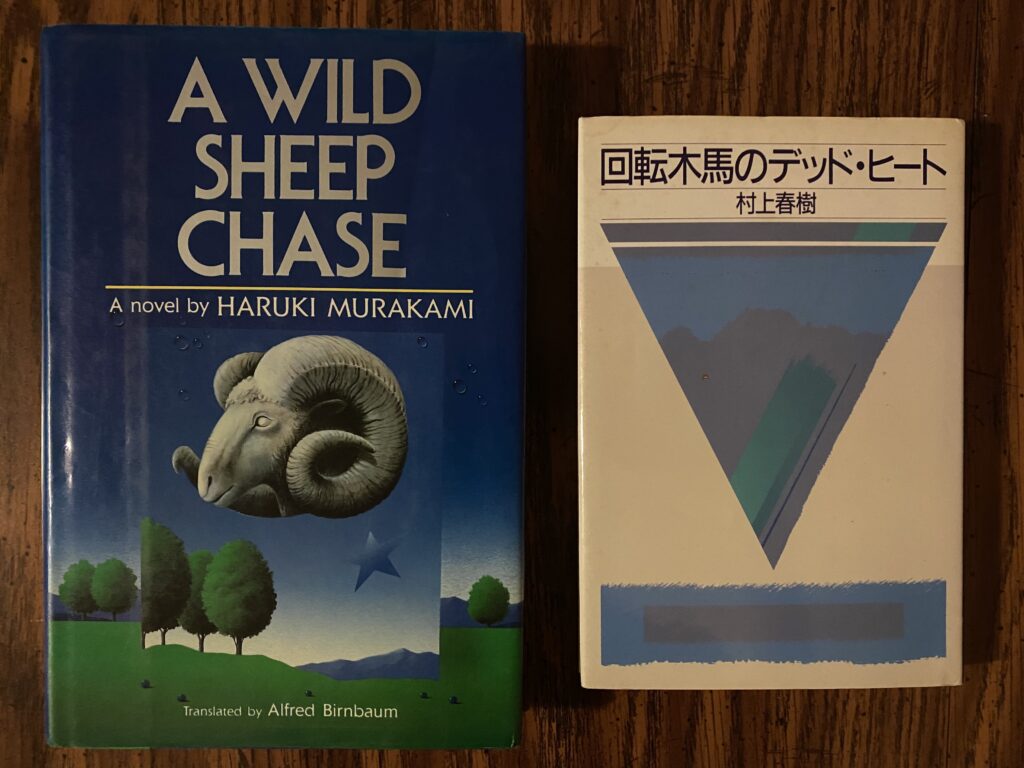

This is pretty wild to me because they’re so totally different. The former is so abstract while Sheep is more surreal. I actually own a copy of both. A friend got me A Wild Sheep Chase years ago, and the Dead Heat first edition was one of the first purchases I made when I moved to Japan…I imagine it was significantly less expensive. You can see more of Okamoto’s work

This is pretty wild to me because they’re so totally different. The former is so abstract while Sheep is more surreal. I actually own a copy of both. A friend got me A Wild Sheep Chase years ago, and the Dead Heat first edition was one of the first purchases I made when I moved to Japan…I imagine it was significantly less expensive. You can see more of Okamoto’s work