Year 1: Boobs, The Wind, Baseball, Lederhosen, Eels, Monkeys, and Doves

Year 2: Hotel Lobby Oysters, Condoms, Spinning Around and Around, 街・町, The Town and Its Uncertain Wall, A Short Piece on the Elephant that Crushes Heineken Cans

Year 3: “The Town and Its Uncertain Wall” – Words and Weirs, The Library, Old Dreams, Saying Goodbye, Lastly

Year 4: More Drawers, Phone Calls, Metaphors, Eight-year-olds, dude, Ushikawa, Last Line

Year 5: Jurassic Sapporo, Gerry Mulligan, All Growns Up, Dance, Mountain Climbing

Year 6: Sex With Fat Women, Coffee With the Colonel, The Librarian, Old Man, Watermelons

Year 7: Warmth, Rebirth, Wasteland, Hard-ons, Seventeen, Embrace

Year 8: Pigeon, Edits, Magazines, Awkwardness, Back Issues

Year 9: Water, Snæfellsnes, Cannonball, Distant Drumming

Year 10: Vermonters, Wandering and Belonging, Peter Cat, Sushi Counter, Murakami Fucks First

Year 11: Embers, Escape, Window Seats, The End of the World

Year 12: Distant Drums, Exhaustion, Kiss, Lack of Pretense, Rotemburo

Year 13: Murakami Preparedness, Pacing Norwegian Wood, Character Studies and Murakami’s Financial Situation, Mental Retreat, Writing is Hard

Year 14: Prostitutes and Novelists, Villa Tre Colli and Norwegian Wood, Surge of Death, On the Road to Meta, Unbelievable

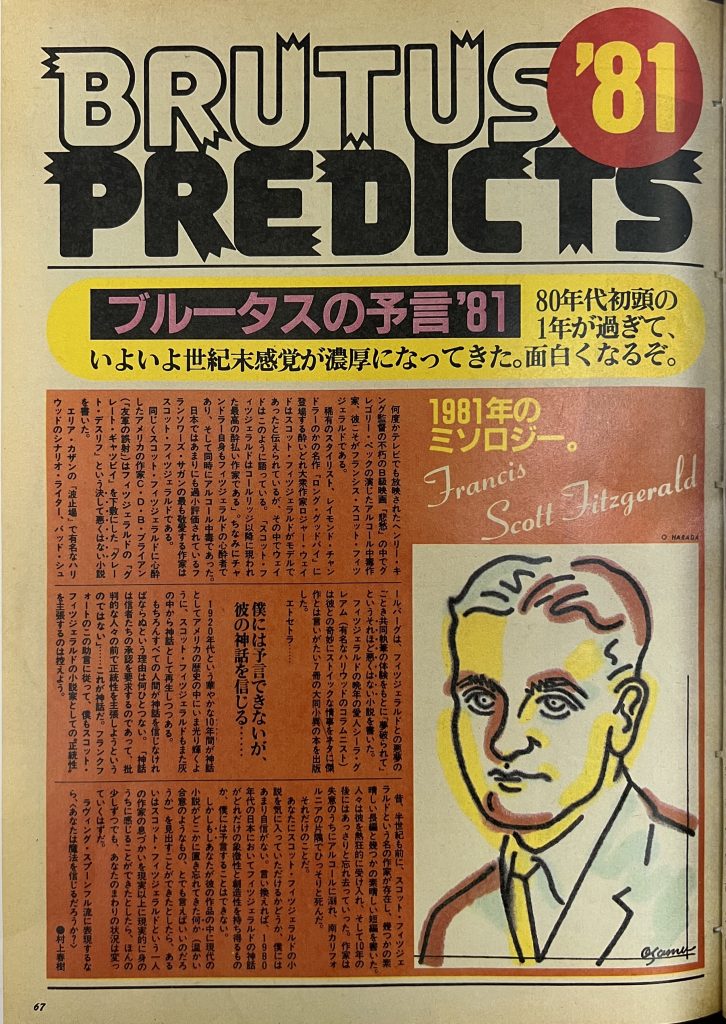

Year 15: Baseball on TV, Kindness, Murakami in the Asahi Shimbun – 日記から – 1982, The Mythology of 1981

I’ll finish up Murakami Fest this year by returning to where I started: Murakami’s 1978 baseball revelation. I’ve looked at a number of his early accounts but only his 2007 What I Talk About When I Talk About Running when it comes to more recent accounts.

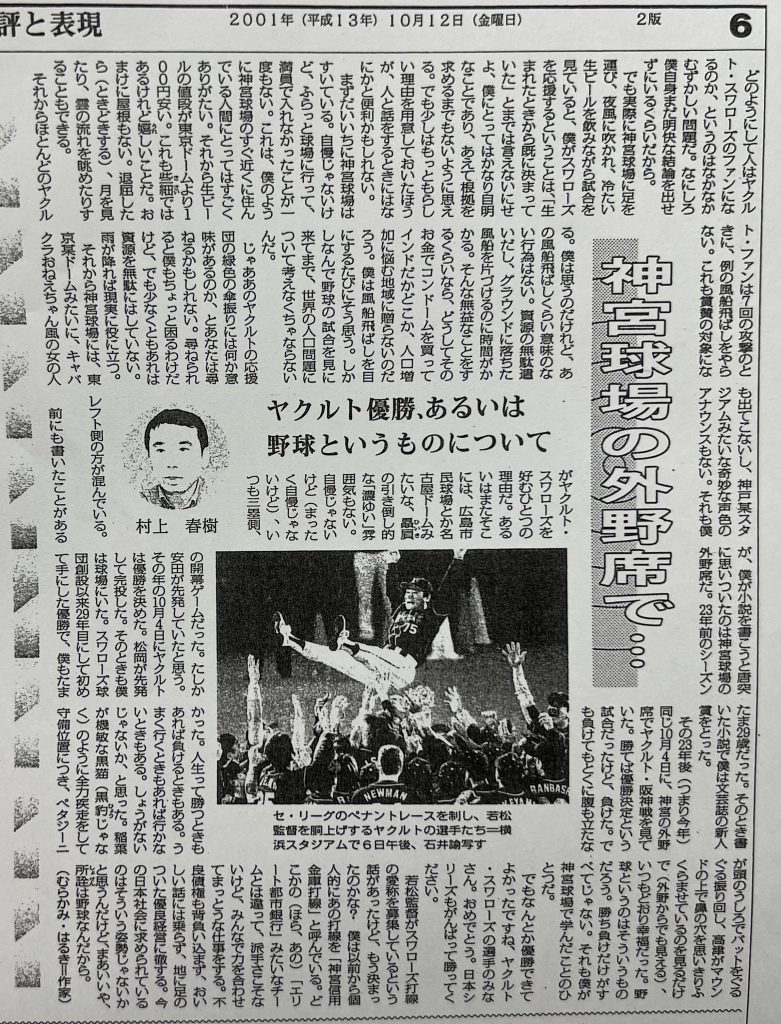

At the Diet Library, I tracked down a 2001 Mainichi Shimbun article Murakami wrote on October 12 ahead of the Japan Series that year. The Swallows played the Kintetsu Buffaloes starting a week later, and Murakami wrote an article on the Culture page about how he became a Swallows fan. He says he doesn’t really know, that he basically realized he was a Swallows fan the day he first walked into Jingu Stadium, but that whenever people ask him about it, he always mentions the few benefits of being a Swallows fan: Jingu is never full, so it’s easy to get a ticket. Beer is 100 yen cheaper than at the Tokyo Dome. And they don’t do the traditional 7th inning balloon release at Jingu, of which Murakami notes “I can’t think of a more meaningless thing to do.”

Here’s what he has to say about the day of his revelation:

I’ve written about this before, but the outfield seats at Jingu Stadium are where I suddenly realized I wanted to write a novel. It was opening day 23 years ago. I think Yasuda [Takeshi] was starting. On October 4 that year, the Swallows won the championship. Matsuoka [Hiromu] was starting and pitched a complete game. I was in the stadium that day as well. It was the first championship for the Swallows, 29 years after being founded, and I happened to be 29 years old. I won the new author’s prize for the novel I wrote that year.

23 years later (so this year), I was in the outfield seats at Jingu on October 4 again, watching Yakult against Hanshin. If they won the game, they would’ve won the series, but they lost. Even though they lost, I wasn’t all that mad. In life, sometimes you win, and sometimes you lose. Somethings things go well, and sometimes they don’t. There wasn’t anything I could do, I realized. It made me happy to see Inaba [Atsunori] sprint at full speed out to his spot like a shrewd black cat (not a black panther), [Roberto] Petagine spin the bat behind his head, and Takatsu [Shingo] flare his nostrils widely on the mound (which you could even see from the outfield). That’s what baseball is all about. It’s not just about winning and losing. That’s something else I learned at Jingu Stadium.

前にも書いたことがあるが、僕が小説を書こうと唐突に思いついたのは神宮球場の外野席だ。23年前のシーズンの開幕ゲームだった。たしか安田が先発していたと思う。その年の10月4日にヤクルトは優勝を決めた。松岡が先発して完投した。そのときも僕は球場にいた。スワローズ球団創設以来29年目にして初めて手にした優勝で、僕もたまたま29歳だった。そのとき書いた小説で僕は文芸誌の新人賞をとった。

その23年後(つまり今年)同じ10月4日に、神宮の外野席でヤクルト・阪神戦を見ていた。勝てば優勝決定という試合だったけど、負けた。でも負けてもとくに腹も立たなかった。人生ってい勝つときもあれば負けるときもある。うまく行くときもあれば行かないときもある。しょうがないじゃないか、と思った。稲葉が機敏な黒猫(黒豹じゃなく)のように全力疾走をして守備位置につき、ペタジーニが頭のうしろでバットをぐるぐる振り回し、高津がマウンドの上で鼻の穴を思いきりふくらませているのを見るだけで(外野からでも見える)、いつもどおり幸福だった。野球というのはそういうものだろう。勝ち負けだけがすべてじゃない。それも僕が神宮球場で学んだことのひとつだ。

Not noted here is that the Swallows did end up clinching, advancing to the Japan Series, and then going on to win after the publication of this article.

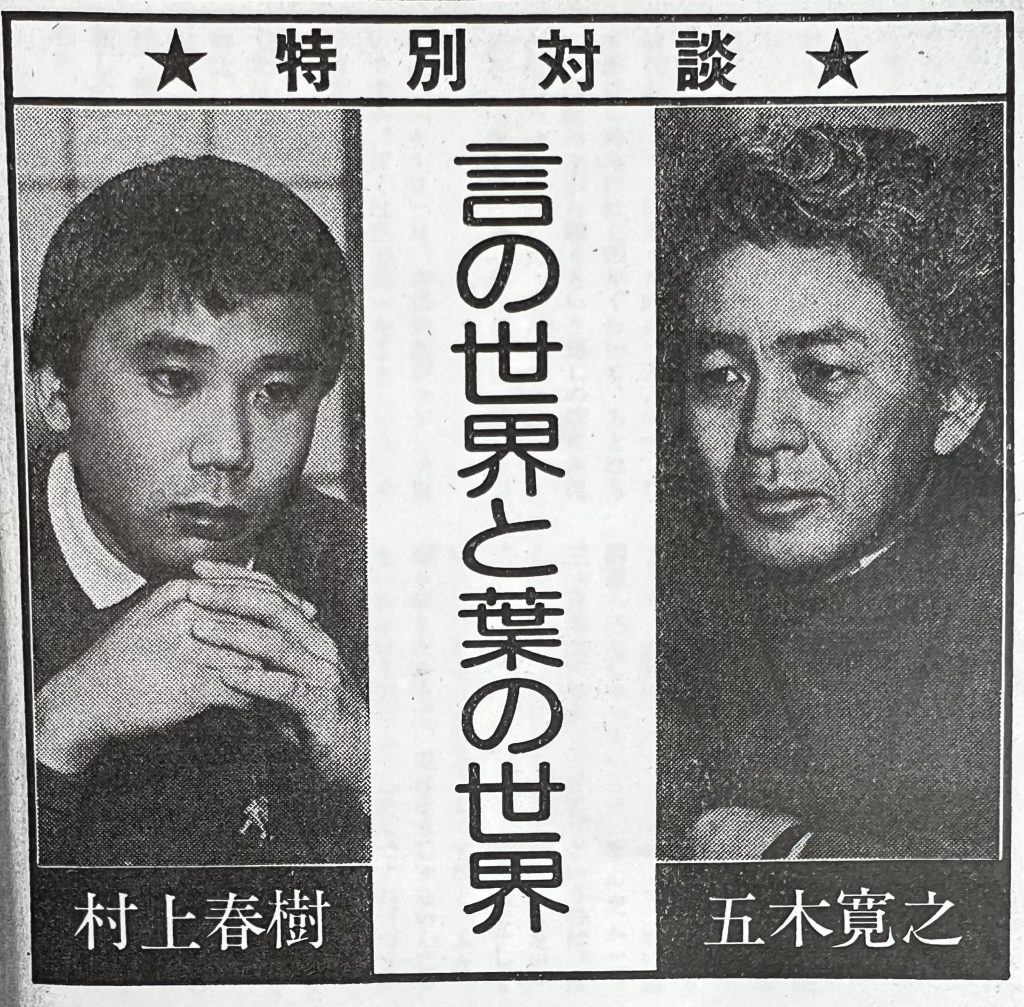

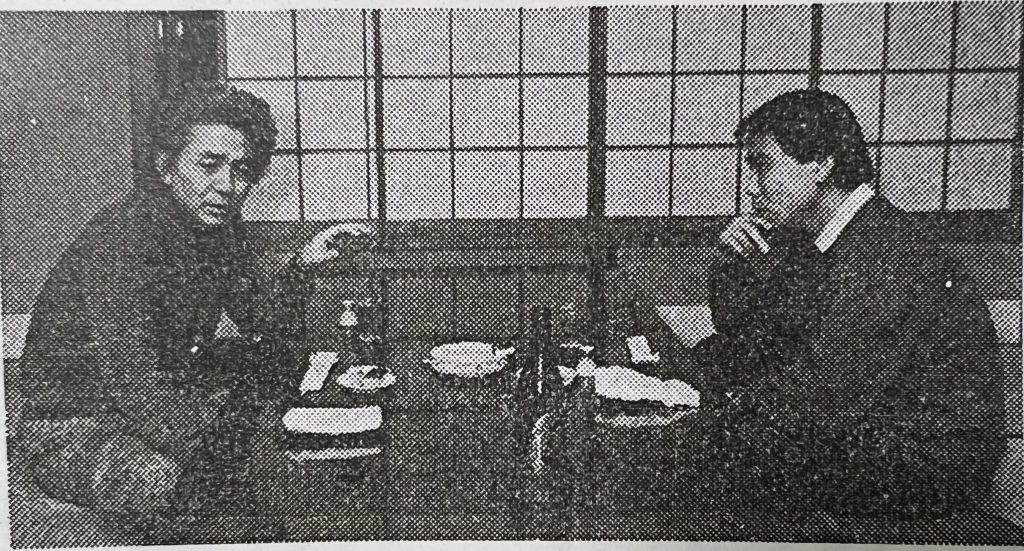

So we have all these accounts, and in only one of them does Murakami claim he was watching on TV. I’m willing to attribute it to the journalist doing the interview, especially given that it wasn’t formatted as a clean transcript. And given that a year earlier in the 対談 with Murakami Ryu, he’d given a very detailed account of the basic story that he’s stuck to over the years. It would have to have been a fairly significant slip up for Murakami to relax enough to deviate from a constructed story, if indeed it was false.

That said, it’s definitely an interesting wrinkle.

Assuming he did actually have the revelation at the stadium, what actually happened that day, on the other hand, is more up in the air, and there’s not much that can be done to definitively prove anything, short of someone finding Murakami in the background of a photograph in Jingu Stadium or in a photograph of Kinokuniya. Now that’s something I’d love to see happen.

Bizarrely enough, the Yakult Swallows are at the top of the standings this year behind the powerhouse hitting of Murakami Munetaka. They play the Hanshin Tigers at Koshien on Sunday. Maybe I’ll look into getting tickets…

Hope y’all have a great year. See you in 2023 for Murakami Fest 16!

Rather than pick out one representative, I thought I’d give an overview of each and a few quotes here and there. That feels more helpful to characterize this moment in time. The series as a whole is an interesting look at Murakami early in his career. Before diving in, take a minute to think about the context here. This is Murakami writing a micro-essay in the paper of record (albeit the evening edition) for two weeks straight, six months before A Wild Sheep Chase, his third novel, would be published and draw the attention we saw with the conversation with Itsuki Hiroyuki last week. I imagine the editors had a need to fill word count, but it’s still pretty remarkable.

Rather than pick out one representative, I thought I’d give an overview of each and a few quotes here and there. That feels more helpful to characterize this moment in time. The series as a whole is an interesting look at Murakami early in his career. Before diving in, take a minute to think about the context here. This is Murakami writing a micro-essay in the paper of record (albeit the evening edition) for two weeks straight, six months before A Wild Sheep Chase, his third novel, would be published and draw the attention we saw with the conversation with Itsuki Hiroyuki last week. I imagine the editors had a need to fill word count, but it’s still pretty remarkable.

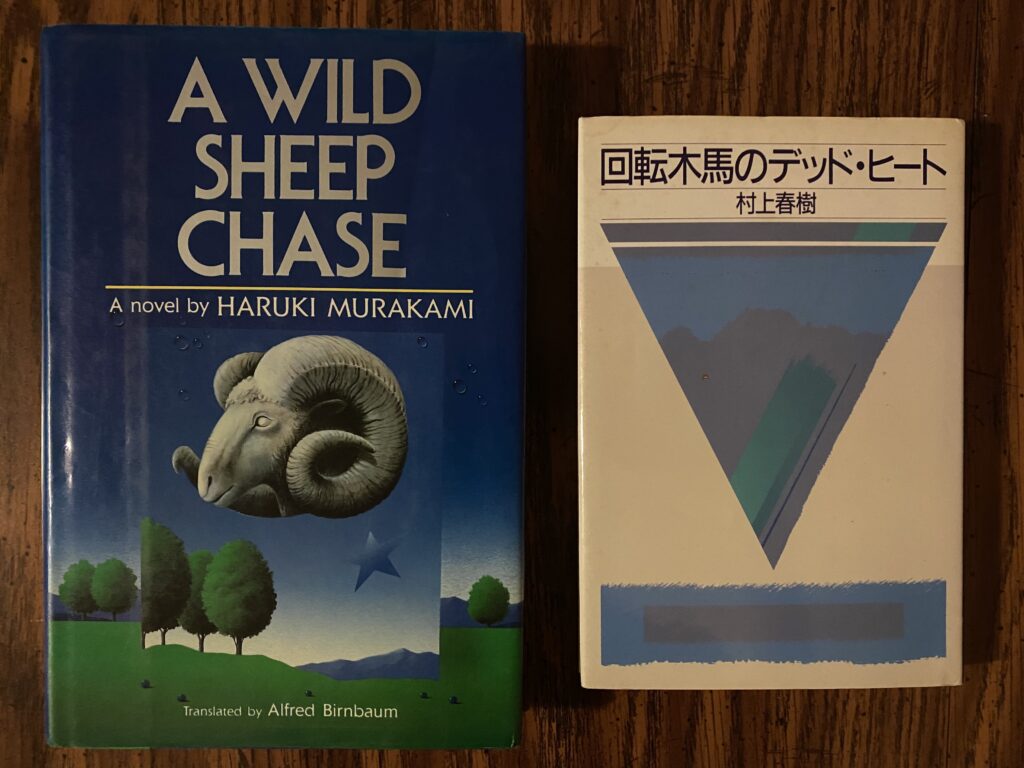

This is pretty wild to me because they’re so totally different. The former is so abstract while Sheep is more surreal. I actually own a copy of both. A friend got me A Wild Sheep Chase years ago, and the Dead Heat first edition was one of the first purchases I made when I moved to Japan…I imagine it was significantly less expensive. You can see more of Okamoto’s work

This is pretty wild to me because they’re so totally different. The former is so abstract while Sheep is more surreal. I actually own a copy of both. A friend got me A Wild Sheep Chase years ago, and the Dead Heat first edition was one of the first purchases I made when I moved to Japan…I imagine it was significantly less expensive. You can see more of Okamoto’s work